One winter in the early 1980s, the Empty Space Theatre was running a production of Tartuffe when one of the actors bailed to be in a movie. "Midrun and he was gone in two days," said Carl Sander, a longtime theater artist who now works at the Burke Museum. Losing an actor to another gig can be a producer's nightmare.

Not this time. "Nobody batted an eye," Sander said. "Everybody was jazzed."

The actor was Kyle MacLachlan, who'd just been raptured out of Seattle theater to star in David Lynch's Dune and begin his celebrated film career.

That may be one of the happier bailing stories I've heard over the years. Normally, unless there's a budget for understudies, an actor bailing in the middle of a show leaves a theater with two tough options: cancel performances and refund tickets, which hurts an already-hurting theater, or scrounge up a replacement, which can hurt the other artists who have to sacrifice time they'd set aside for other work or family to dive back into the rehearsal hall with the newcomer.

Here's a less happy bailing story: A few months ago at a small Seattle theater, an actor bailed on a show. It wasn't the kind of bail every director would automatically forgive: no sudden illness, no death of a loved one. It was a bail for professional reasons. On the Tuesday before the closing weekend of the production, the actor called the director and said he had to go. He said he was offered another gig in another town with more visibility and much better pay than the stipend he was getting at the small theater, as the director, who only agreed to talk if I didn't name names, recalled. The actor was very sorry, but he just couldn't afford to turn it down.

The director wasn't happy. The play was a spare, intimate, and emotionally tense show in a small room. There was no understudy, and the director didn't want one of the actors stumbling through closing weekend with a script in his hand. The theater canceled its final, sold-out performances. The actor declined to comment for this story, saying only that it was "an extremely difficult decision."

I agreed to withhold identifying details about the people involved because this isn't about naming and shaming—and the question of what an actor owes a theater isn't always clear-cut. When is an actor justified in breaking a contract or a handshake agreement? Oftentimes, theaters will try to keep a bail quiet, not wanting to talk about the wrinkle until it's smoothed out. A couple of people I contacted for this article even scolded me for digging into it. This incident was awkward and painful for a small theater company, and it happened months ago—why bring it up again?

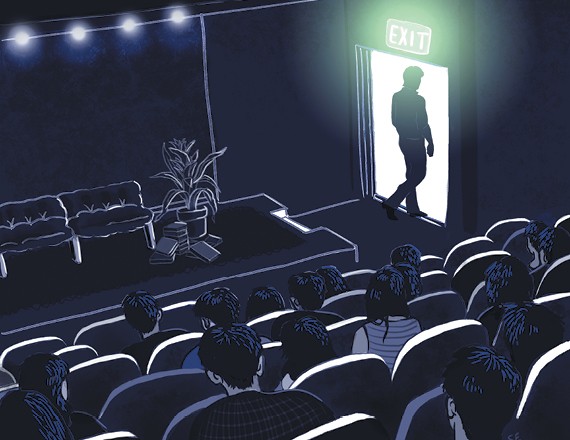

One reason: Bailing is a special problem for performance. You can build an art show and then hide out; you can mail music tracks back and forth (and even get famous for it, like the Postal Service); you can reshoot a film and edit it to obscure crises. But live theater and dance require presence: these people in this room at this time.

Sometimes, those people bail. The sound designer can't stand the director, an ensemble member's mother is dying, an actor who's also a union representative quits in protest because he thinks the theater has systematically violated other actors' contracts. Those are all true Seattle stories.

Should an actor finish the production they've consented to be in and pass up the big opportunity? Would passing up the big opportunity in such a precarious profession be loyal but idiotic? What are the ethics of bailing?

"All bailings are not created equally," said Laurence Ballard, who worked around the country as an actor for decades and now teaches at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Theater, he says, is "a people industry with 1.5 incestuous degrees of separation," and "your word is your bond." In that world, where gossip spreads quickly and hard-earned reputations can sometimes be broken with one bad decision, bailing tends to be its own punishment. But if "you get the offer of a butt-load of money—a featured/leading film role—sure. And most of the time, people will understand. Mazel tov, fucker."

If one of Ballard's students were presented with a quandary like this, I asked him, what would he advise? "Is the money good? Will it further my career? Will I have a good time?" he asked. "If the answer is 'yes' to any two, take the contract... Growing up is a series of bridge burnings."

The director of the local production that recently had this problem didn't take such a long view: "He did not give two weeks' notice. He quit and created a business crisis." Would the director have hired him if he knew he had a potential conflict? "The answer is 'no,'" he said. "We have no staff, no understudy in waiting, and no money... So what is the actor's ethical decision in such a situation?"

He left the question hanging.

"People gotta eat," said playwright Courtney Meaker. "I don't know any actor that takes the issue lightly." She admitted that no actor had ever bailed on one of her shows midrun, which might change her attitude—at least temporarily. "I've been friends with actors who've been faced with the quandary, though, and have to side with economics," she said. "Actors make very little money as it is. If a big opportunity knocks, I think you have to answer the door."

A few weeks after the local production closed, a handful of film and theater artists gathered for supper on a back porch and debated the ethics of bailing. One had worked in an ensemble with a loyal actor who declined a job at a regional theater that would've allowed him to break into the union. Another bailed on a production before the first rehearsal because she realized she didn't have confidence in the project. Yet another remembered working on a pilot where one actor couldn't make the shoot, and a young woman helping with hair and makeup was hired on the spot. One artist's bail is another's opportunity.

Mark Siano is an actor, director, and producer with Cafe Nordo and other smaller outfits—but until recently, he worked at ACT Theatre, which has had two notable bailings in the past few months. Dominic Rains, who was in the Portland production of Yussef El Guindi's Threesome, got cast in a feature film less than two weeks before the Seattle opening. Karan Oberoi, a screen actor, got the part and learned it in less than a week—and a few weeks after that, he was playing in Threesome's off-Broadway production and getting a positive mention from Charles Isherwood in the New York Times. "As far as people being upset with Dominic," Siano said, "the people most upset were me. I had to set up a whole new photo shoot!"

This was yet another instance when the theater wasn't eager for people to hear about the bail—in early press materials, before the updated photo shoot, Siano quietly cropped images from the Portland press materials to cut Rains out of the picture.

How does Siano feel when actors bail on his smaller-scale productions? "I'm never paying people enough," he said. "If something more lucrative comes along, you have to take it. Those are the unwritten rules of theater." But it has to be worth it, he says—not just something you think some LA agent will see, but "serious screen time or a leading role in a Netflix show... leaving for a walk-on role in Grimm would be bullshit."

Siano admits he's bailed on shows in the past for less than ironclad reasons. As a teenager, for example, he left an Everett production of The Mikado after one rehearsal because he didn't really like the music or the people. He also left a long-ago fringe-festival production after one rehearsal because the company was such a mess. "If you go to the first rehearsal and say, 'These guys are idiots,' you might never get to work with them again," he said. "But maybe that's not such a bad thing."

As for Kyle MacLachlan's bail, nobody seems to remember hard feelings—in part, the artists working on the show say, because MacLachlan was up-front about developments as they were happening.

"Performers rarely get the best end of a bad situation," Sander said. "And when they do, it's incumbent on the producers to make the best of it." ![]()