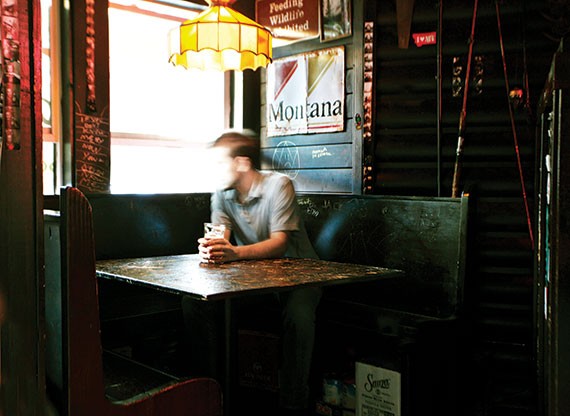

Joel Reuter used to drink at Montana, a black-lacquered, lovingly graffitied Capitol Hill bar with lots of regulars and cheap cocktails on tap. His apartment was only a few blocks away. Most mornings, Joel would wake up and walk his floppy-eared toy King Charles spaniel, Telly, to meet his friends at Analog Coffee. Then he went to work at a job he loved near South Lake Union—he was a software developer. Then after work, he and Telly (who was named after the Radiohead song "Planet Telex") would wander down to the dark and cozy Montana for happy hour. Joel would grab a seat at the bar, order a Moscow Mule on tap, and gently flirt with the bartender, David, until his friends arrived. He was a great listener, and jokester, but rather private about his personal life.

"He was really soft-spoken, really sweet," David recalls. "It wasn't until he started coming in alone that I got the impression he was gay."

"I didn't know he was gay until we were trying to remember Judy Garland's name," Joel's close friend Julia recalls. "He said, 'All gay men know the phrase 'Are you a friend of Dorothy?' And I thought, 'Joel just told me that he's gay.' He didn't talk much about his sexuality."

Joel's friend Duncan says, "He was the guy who would send you a text saying, 'I got a bunch of tickets to see this awesome band—you wanna go, right?' His attitude always was: 'I've got this all set up; I just want to hang out with you.'"

People didn't just want to hang out with Joel, they moved to Seattle to hang out with Joel. Duncan and Joel went to college together in Tucson, and when one of Duncan's college friends was having a rough time in Tucson, "Joel bought him a plane ticket to Seattle and let him sleep on his couch until he found a job," Duncan says. Same goes for another man Joel met at Sasquatch! music festival two years ago. That man also uprooted his life and ended up living rent-free on Joel's couch while he figured out his life.

"Any time he could help you out in any way, he'd do it," remembers Alex C., another friend. "It wasn't something he even had to think about. That was just who he was."

He was a teddy bear—"a handsome, alopecia-stricken, six foot four teddy bear," one friend jokes. "Maybe an oak tree crossed with a bald teddy bear." He was a 28-year-old tech geek with a dimple in his chin and cherubic cheeks always on the verge of a smile.

At least, that was the man his friends knew and loved, before a bout of cancer treatments and a struggle with mental illness seemingly undid him. On Friday, July 5, after an eight-hour standoff, Joel fired a shot at police out of his fifth-floor apartment, and they returned fire, killing him. A crowd had gathered on the streets below, including neighbors, reporters, and seven of Joel's close friends. For them, it was the culmination of a tragic seven-month-long nightmare that began in January, when Joel was diagnosed with lymphoma—blood cancer.

Here's how Joel described himself, his life, and his diagnosis in an undated post on his website:

I'm on chemotherapy and I'm doing well so far. I'm told that I have a great shot at getting it cured over the course of several months of chemo treatments and maybe a little radiation at the end.

I work in one of the coolest places ever. We have pinball games, a gigantic theater, and a kitchen which serves meals three* times a day. We work hard and we laugh hard and we get a lot done. My coworkers have been bringing me meals and spending time with me so I don't have to be alone. I have paid time off to get better. And insanely good health insurance. I love my job.

*Sometimes afternoon cookies, too.

I just got a new car, which is pretty awesome, though I haven't gotten to use its all wheel drive feature much. I wanted to ski more this winter, but it's been difficult, to say the least.

I like to play guitar, make beats on the computer, program lights to flash on an Arduino board, or watch movies and play PC games during my spare time, which has been growing larger.

In January, I started to feel light-headed and dizzy once in a while. I thought it would go away, or that it was an ear infection, or something I could just deal with. It got worse. Eventually I had to go to the Emergency Room because I felt so... weird. They found that my calcium level was very high, and told me to follow up on it the next day. So I did.

And the next day.

And then I was in a world of hurt. I couldn't do anything. Shower, drive, I could barely make it to the waiting room at the doctor's office because my head hurt and I was so emptied out, mentally and emotionally. I just wanted to feel better.

This began the process of going to the hospital, getting tests done (bone marrow biopsies SUCK), and finding out I have lymphoma. That is a tough pill to swallow.

Luckily, my friends have also been amazing. Some stay overnight, some bring me food and flowers, some take me grocery shopping, and some set up crazy websites for my family and friends to stay connected to me. Some have been there while I cried, others have seen me laugh inappropriately at a cancer joke I made out of fear.

I have so much.

What I want to find, and I think I will, is a stronger self as someone who has defeated cancer. I want to walk proudly down the street knowing that I have beaten this thing that could have killed me had I not been so strong.

I am so lucky.

Before Joel began chemo, he and Duncan shaved their heads together. And on that first day of chemo in late February, several friends took the day off work to accompany him (in fact, he never attended a treatment alone).

It was that first night, after chemo, that his friends first noticed a behavioral change. "He was distant," says Alex W., a friend and former coworker. "He stayed up most of the night painting. It was colorful and strange. He was explaining a piece of it to me in such great detail, like, 'This was the alien ship coming down...' It took him half an hour to explain one little section to me. He acted like he was tripping, only he wasn't. Each day after that, he was a little weirder, a little weirder, a little weirder. We thought it was the chemo, but it was like he never recovered from it."

Like his sexuality, Joel hadn't talked about his bipolar diagnosis with many people. The friends who did know say he was studious about his meds and that he'd never had an episode in Seattle. They theorize that the chemo interfered with his medication. After the first few rounds of chemo, he simply stopped taking his meds. The near-daily happy hours at Montana ceased. In four short months, the Joel his friends knew and loved was replaced with someone else: a paranoid stranger. One who bought a one-way ticket to London because he was convinced that both his government and his family were out to get him. Immigration officials at Heathrow Airport immediately put Joel on a plane back to Seattle. He then fled to Canada. Twice.

In this country, we're not great, or even good, at understanding or supporting people who struggle with mental illness. If a person is diagnosed with cancer, it's easier to rally behind them. Their sickness is visceral, treatable, accepted. But there's an overall willingness to dismiss those with mental-health issues as simply crazy or beyond help.

Joel's loved ones didn't do that. They put mental-health groups on speed dial in their phones. They called the cops routinely. They begged for guidance. On two occasions, they had Joel temporarily held for psychiatric evaluation. Each time, he was released before his medications, and his moods, stabilized. They talked of having him committed.

"It's hard to understand, to internalize, that it's not the same person," says Duncan. "He looked the same, but that wasn't Joel."

"Every day was a struggle," remembers Julia. "I remember being on the phone in my kitchen and crying to the Crisis Clinic, 'What's going to make this change? When he finally kills himself?' They said they had no proof he was a threat."

In May, Joel began talking about guns. "He was really antiviolence," Julia and many others stressed. "He was totally freaked out by guns. He would never own a gun. Never."

At some point, Joel bought a handgun without telling his friends. (ATF is currently tracing the sale of the weapon, as it should have been illegal for Joel to purchase the gun after being involuntarily held for mental-health evaluations.) He threatened suicide. He began fixating on religion, whereas the Joel his friends knew was an atheist.

That is the man that police confronted on July 5, the stranger who made the news. At the scene, Joel's friends told police about his recent mental-health problems. They offered to reach out to him, to call him. At one point, Joel appeared on his balcony holding a handgun and reportedly shouted that he was prepared to defend himself against zombies. "What's going on?" asked a bystander, new to the scene.

"Just some crazy guy with a gun," the officer responded, within earshot of Joel's friends.

Joel's friends don't want his memory to be defined by his mental illness. That's not how they will remember him, because that's not what defined him.

Joel was the man you could lean on when it felt like your life was collapsing, his friends say. He was the man who would slow-dance with you after a bad breakup. When you were depressed, he'd be the guy at your door in khakis and a polo shirt, cajoling you into taking a shower and going out dancing. He'd invite you over to his house for a Disney sing-along. He would play Mario Bros. with you. He'd watch Adventureland with you. He'd play guitar with you. He was the guy you'd be most likely to spend eight hours listening to Radiohead with, the guy who would drag you onstage at a Girl Talk show—just you, him, and two dozen sorority houses all shaking your asses.

More than a single story or memory, his wide circle of friends and their loyalty, their commitment to step up and support him through physical and mental illness, stands as a testament to the man Joel was.

"He might not be the loudest guy in the room, the guy who starts parties, but he was the guy you could talk to about your problems. The guy who'd make you laugh," says Julia. "He was Joel, and we're going to really, really, really miss him." ![]()