--Priceless Game, "Once a Playaz Gone..."

Phillip Tyrone GriffIn was looking for a way out. He was tired of the petty hustles, the long hours sitting around talking big but doing nothing. He believed he had the street cred, the look, and the sweet flows. He had what it took to make it in the music business. And when, by chance, he hooked up with a group of white kids who had the talent and equipment to help him make his dream a reality, he was sure he'd finally get his chance to make a great rap record, and wouldn't be living that sorry-ass hand-to-mouth ghetto life much longer.

He was right on both counts.

Just past midnight on Tuesday, August 13, Phillip Tyrone Griffin (aka "Priceless Game," aka "P.G.") was seen talking to two or three men under an overpass in the International District, at the base of the stairway leading up to the Yesler Terrace housing project on the 800 block of South Jackson Street. One of the men pulled a gun and fired a single shot, striking P.G. in the chest. P.G. ran across the street to a parking lot, where he collapsed and died.

One hundred and seventy-three words: 116 in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 57 in the Seattle Times. That's all Griffin's murder received in the Seattle dailies. Hardly enough to provide the barest facts, nowhere near enough to sum up a life--or even explain a death, particularly the violent, senseless murder of a 23-year-old man on Seattle's streets.

Phillip Griffin ain't coming back, but he's not forgotten, not by Richard Weisner. Weisner, aka the Wise, a white beatmaker, is a thin, youthful-looking guy, dressed casually in T-shirt and jeans and wearing a baseball cap. He appears to be on the verge of tears in The Stranger's conference room as he talks about P.G. dying barely 48 hours earlier. P.G. was his friend and his musical collaborator. There's more to the story of Priceless Game, he insists, than the circumstances of his death. P.G. was a gifted rapper, Weisner asserts, the real deal. He was a kid who could take the raw pain and anger born of a harsh upbringing and string it into words, into something approaching art. He may have begun with next to nothing, but he was perhaps on the verge of it all: money, success, fame.

Weisner worked intensively for five months making the beats for P.G.'s first record, recorded in the $30,000 basement studio of Weisner's housemate Dean Swanson, a trained audio engineer. They were a week--one last track--away from finishing the project, from finally getting it out on the street, when his friend was killed. He says now that last cut will have to change--he'll bring together all of P.G.'s friends to record a tribute track, à la Puffy, for his fallen comrade.

At the moment, he's left with the other nine songs, burned onto the CD in his hand. And, surprisingly, they're actually very good, maybe even great. In fact, given its humble pedigree, P.G.'s CD is a remarkably slick record, a professional production better than most big-money, major-label studio stuff, according to rap reviewers who critiqued it for The Stranger. The beats are catchy, melodic, and poppy with a techno touch, and P.G.'s rapping is smooth, a little silky, in the classic West Coast style. But it's the lyrics that stand out, given what we know of their author's demise. They're the words of someone who claims to know something of violence, pain, and death. Now they seem eerily self-referential, a dead rapper's personal epitaph sung from beyond the grave.

How much pain / Can one man endure? / I'm still not sure / What I'm living this life for

--Priceless Game, "How Much Pain"

On a hot August Thursday, people gather at the Dayspring & Fitch Funeral Home, a white clapboard building across from an auto-parts store on a nondescript stretch of Rainier Avenue. In an upstairs room, nestled in an open baby-blue coffin with elaborate metal fittings, rest the corporeal remains of Phillip Griffin. Upbeat, even jaunty, gospel music plays in the background--"Jesus, we rejoice," the chirpy voices sing--as a steady stream of mourners, mostly black women--aunts, cousins, girlfriends--enter to pay their respects.

Weisner spends a few minutes quietly communing with his departed friend. P.G. lies with eyes closed, hands folded formally over his chest. Dressed in a favorite red sweatshirt, there's no visible mark of the violence that took his life. He looks so lifelike that Weisner reaches out and touches his hand to make sure it's cold. Satisfied he's gone, Weisner places a copy of the finished CD in his friend's lifeless fingers; the disc is adorned with a picture of P.G. rapping into a microphone, with the Seattle skyline in the background.

The funeral, held the following morning, draws a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 200 friends and family members. "P.G. was a 'hood celebrity," one of P.G.'s friends tells me. Looking out over the crowd, that doesn't seem like an exaggeration.

Before the sermon, someone plays one of P.G.'s tracks, "He Don't Know," for the assembled; it's a beautiful song with haunting female background singing, though the raps, built around boasts of sexual conquests, are typically raunchy. Given the solemnity of the setting, the choice is jarring. Luckily, the speed and intricacy of P.G.'s flows prevent most of the older attendees from picking up on what the song is actually about. P.G.'s friends admit to feeling uncomfortable that his family chose that song to play.

"It's not the one I would have picked for that sort of occasion," one says several days later.

"P.G. considered himself a player, not a gangster," Weisner tells me as he looks at the Seattle skyline in the distance. "He was always careful with his terminology." Weisner is sitting on a ratty yellow couch on his porch. The house is a big, rundown place on 29th Avenue off of Massachusetts Street. Inside it's dirty and almost devoid of furniture, a fitting residence for a group of poor kids working dead-end, part-time jobs as they sacrifice for their art. He chuckles. "He was a good-looking guy. He described himself as 'the caramel cat with the nose ring.'" Theirs was an unlikely collaboration.

Richard Weisner is a 24-year-old Jew from Las Vegas, here in Seattle for less than a year. P.G. was born and raised in the Central District, street tough, ghetto tested--in a city too nice and too white to admit to having a ghetto--with the police jacket to prove it. "We were from different worlds," Weisner says.

"P.G. was a natural born hustler," contends Joe Stuhff, Weisner's housemate. He's the aspiring white rapper who first invited P.G. to come over and record after meeting him on a bus last March. "He came in here and practically took over, turned the whole house upside down. I'd wake up in the morning and there he'd be, eating our ramen."

Soon, P.G. was amazing them with his offbeat skills: "I'd like to know where a black guy from the ghetto learned to ride a unicycle," says Shawn Diaz, another housemate. Most of all, within weeks of his first visit, P.G. infected the entire house with his dreams of wealth, fame, and musical glory.

Though he had no money to pay for the studio time, his new friends were so convinced of his talent--"That first day it was obvious he could rap when he showed us he could freestyle," Weisner says--that they agreed to work with him on his recording project. Soon P.G. began bringing over other rappers from Central, and with the eventual addition of jazz-trained female backing vocalist Soo Jin Yi, the project really took off.

"We had a Jewish beatmaker, an Asian vocalist, a white rapper, and P.G. and his friends. Only in Seattle," Weisner says.

P.G. took the work seriously--perhaps too seriously. One incident stands out. Unsatisfied with the slow pace of the recording sessions, one night P.G. completely lost control and began screaming that Weisner and his housemates were dawdling and weren't giving 100 percent to the record project, that they were conspiring against him and holding him back. "That day I saw another side of him," Weisner says, though he insists he never felt threatened: "We just saw that anger as an expression of his passion for the music."

But Weisner and company were part of only one aspect of P.G.'s life--his drive to make music. There were other hints, beyond the outburst, that the rest of his life was far more troubled. As P.G. grew comfortable with his new friends, he admitted that he did a couple years in prison. He blamed it on his ex-girlfriend, who he said stalked him to a local mall. A fight ensued, the cops were called, and P.G. was caught with a gun, leading to the jail term.

They didn't know what to make of that, but Weisner and his friends were willing to accept P.G., warts and all, because his musical promise seemed so clear.

"We just really, really believed in him," Weisner says.

Wishing I can heal my mama, / Traumatized as a little kid, / From the harsh way I live, / The streets never show me neglect

--Priceless Game, "How Much Pain"

Perhaps no one knows better the two sides to Priceless Game, and the two worlds he inhabited, than Enrique Black, P.G.'s oldest friend and one of the Central rappers P.G. brought into the recording project. Black was dubbed the "vice-president" of Priceless Game Records, P.G.'s music empire-to-be (he also spoke often of the clothing line he planned to issue). Black and P.G. were friends since their days at Washington Middle School but lost touch after P.G. was expelled and during the four years Black served in the Marines, reconnecting only a few months ago when, Black says, P.G.'s work on his record gave him a sense of mission.

"P.G. had a tough life," Black says. "He had to be out on his own on the streets from an early age. If someone else had to walk in his shoes for a day they'd lie down and give up, but he was a warrior--that's what I admired about him most."

Black skirts the subject, but friends and family claim that P.G.'s mother began smoking crack during P.G.'s elementary school years. The family's situation quickly fell apart. P.G.'s mother moved her kids from place to place frequently and sold off their possessions. When there was nothing left, P.G. moved in to his paternal grandparents' home at 29th Avenue and South Washington Street, and his little brother, with whom P.G. was very close, was sent to live with relatives in Kansas City. Their mother all but disappeared.

"P.G.'s mother is basically still homeless," Black says with a shrug when I ask how I might get in touch her.

The collapse of his family had a huge destructive impact on P.G. "He had trouble figuring out how to control his anger," Black says. "Every time things seemed on the right track he'd have a setback." Though P.G. had a place at his grandparents', he spent most of his time running the streets, hustling for money, and getting in trouble with the law.

Out of touch with P.G. then, not even Black knows the whole truth, but a check of King County Superior Court records reveals a laundry list of charges against Phillip Griffin. Ten juvenile offenses are listed, beginning the day after his 15th birthday in 1993, when P.G. faced a "dangerous weapon" charge. Others followed, including theft, reckless endangerment, and robbery, four charges total in 1995 and three in '96. Then, as an adult, he faced a third-degree assault charge in 1997 and again in March 1999, when he was also charged with possession of a firearm for the mall incident.

P.G.'s cousin Katina Malone concedes that P.G. had developed a terrible temper by the time he moved in with his grandparents, but adds the family understood that he was acting out over the loss of his immediate family. By his teens, P.G. was turning to numerous girlfriends for love. At 17, she reveals, he impregnated a neighborhood girl named Amber, who gave birth to a son, now five years old, named DeMarion. Theirs was an ugly, stormy relationship. One time P.G. spit on Amber, Malone remembers, and a few weeks later he discovered another man at Amber's house (she lived with her parents), and a nasty fistfight ensued.

Things got even worse after Amber found a new, serious boyfriend, who went by the name of "Munster." P.G. and Munster were involved in "a series of incidents" culminating in a terrible fight; that's the one that prompted P.G.'s first assault charge, Malone thinks. Amber finally took out a restraining order against P.G. "She was scared of him. She'd say P.G. was crazy," Malone recalls.

Eventually, he got involved with another girl. That girl also took up with a new boyfriend, but P.G. couldn't let go--court records indicate P.G faced a civil domestic-violence charge in February 1999. Malone doesn't know the details of the mall dust-up the next month that led to P.G.'s incarceration, but freely admits the incident was instigated by P.G. "He just snapped," she says.

There was also a more recent incident of violence. In mid-June of this year, P.G. turned up at Weisner's house with a huge stitched-up cut on his head. The way P.G. told it, he'd unexpectedly run into Munster outside a downtown gym. Munster pulled out a box cutter and slashed him. Nonetheless, P.G. didn't report the incident to police. (After P.G.'s death, a police detective tells one of P.G.'s friends that Munster could not have been responsible for the slashing incident, since he was in jail at the time.)

Whatever his problems, Priceless Game "was a survivor," Black believes. P.G. was fond of articulating a philosophy of life he called his "Rules of the Game": Play the hand you were dealt, take adversity on the chin, and keep striving to get ahead. On the other hand, "He didn't like to worry too much about what had happened in the past," Black says. "He said he didn't have time for that."

Doe Mackin, 26, had known P.G. for nine years. Mackin had some recording equipment, and they'd practice recording beats and raps. From the outset, P.G. believed rapping would be his ticket to a better life. "He was a music-business dude," Mackin says. "He'd tell me, 'You're going to be my business agent, you're worth a hundred G's, dog,' and this is when I was 17, and he was just a 15-year-old kid."

But it wasn't until P.G. got out of prison that he began chasing his dream with focused, almost maniacal intensity. He started showing up at Mackin's place to press his friend relentlessly to help him make his record. "He was after it 24-7, I mean, he was the Energizer bunny," Mackin says. Mackin didn't have the time or equipment to realize P.G.'s ambitions, but it was impossible to get that through to his friend. "I must have told him to hold on, wait for the right situation, 800 times."

P.G. found the right situation on the #14 bus as it rolled down South Jackson Street. Joe Stuhff, one of Weisner's housemates, was riding in the back when he overheard P.G. telling a friend about his desperate need to find a studio to record his growing stack of rap songs, squirreled away in the backpack at his side. Stuhff interrupted, telling P.G. of Swanson's studio and inviting him to come check it out, and P.G. turned up a couple days later. As his collaboration with his new friends took off, P.G. started coming over a couple nights each week, sitting up late with Weisner working on beats and lyrics. Usually he'd crash on the beanbag chair in Weisner's living room when they finished.

The project seemed to prompt a major turn for the better in P.G.'s life. When he first started coming over to the house, he was still hustling, Weisner says. What that involved isn't clear, though he was almost certainly dealing a little weed, and perhaps harder stuff. But as his faith in what they were doing grew, "he began backing out of the game." Weisner told P.G. that he had a good thing going with the record and he needed to be careful not to mess that up. "He slapped my hand, snapped his finger, and said, 'Yeah, I feel that for sure,'" Weisner recalls.

In fact, things were going so well that he even told Black he was thinking of going back to school. He had eventually attained his GED, and now began talking about enrolling in community college.

On Sunday, August 11, they recorded P.G.'s ninth track, and were planning to do one more the next week. Impatient to get his music out, several weeks earlier P.G. had already sold 50 CDs of the rough mixes to friends and acquaintances at $10 a pop. But now they were on the verge of having a final version, and P.G. talked of big plans to shop the disc around to stores and radio stations, and to seek out a serious distribution deal.

"The happiest I ever saw him was when he was right here in the studio," Black states. "He was a musical genius. He could put aside all the other hard parts in his life. He kept saying, 'This one's gonna go platinum, this will get us out of the 'hood.'"

But the next morning started with P.G. in a bad mood, which got worse as the day progressed. Black was with him for much of that day, and nothing seemed to be going according to plan. For one thing, P.G., a daily pot smoker, was out of herb and couldn't lay his hands on more. Then he got into an ugly argument with a bus driver who told him he couldn't eat an ice-cream cone on the bus, and another with his aunt. "It was little things like that that'd get on his nerves," Black says. Other things went wrong as well, and by that night P.G. was really pissed. "He let his anger consume him to the very end," Black says. "If anyone gave him a foul look, he'd be snapping at them."

The reason P.G. was shot remains murky however. Neither the police nor the medical investigator's reports reveal anything beyond the basic facts: the encounter, the gunshot, Phillip Griffin DOA at the scene. The Seattle Police Department refused my request to interview the detectives on the case, saying it's still under active investigation. Detectives recently told P.G.'s aunt they have a likely suspect, but have yet to make an arrest.

Was it a chance encounter with strangers, fueled by P.G.'s temper, which was close to the boiling point the whole day? Or could the men he encountered have included one of his ex-girlfriends' new beaus? Black doesn't know and refuses to speculate. He called it a night just before midnight Tuesday and headed home, while P.G. headed downtown on Eighth Avenue. Five minutes later he was dead.

Katina Malone says neighborhood rumor has it that P.G. was killed by a Bloods gangbanger named Leon. Allegedly, P.G. happened upon Leon beating up a girl he knew. When he intervened, Leon pulled a gun and shot him. The police report, however, makes no mention of a woman at the scene or of any fight preceding the shooting.

I'm a player who went to my gangster side, / Who the hell said only gangsters ride? / I'm a P.G.P. Priceless Game Player, / I smile in your face and deal with you later.

--Priceless Game, "H is for Homicide"

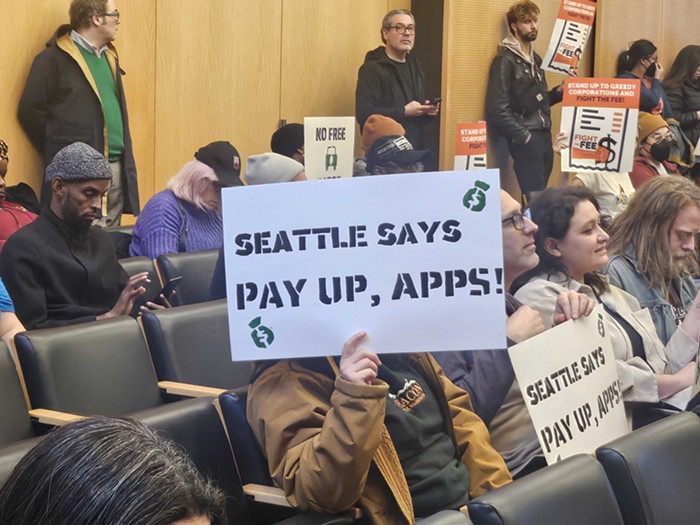

Keith Asphy, aka Keek Loc, aka the Ghetto Prez, is cruising the streets of Capitol Hill in his SUV, dubbed "Marine One" (his other ride is Air Force One). He pops P.G.'s CD into the stereo and cranks the volume. At 27 he's a veteran Seattle rap music entrepreneur. Besides his own rap label, Seasick Records, he promotes hiphop shows, owns a distribution company, does graphic design for record labels, and has begun publishing Seaspot, a magazine on Pacific Northwest rap. P.G., because of his recent stretch in prison, was not a well-known figure in Seattle's rap underground, but Keek knew him slightly and heard about his death. Until now, however, he hasn't heard any of P.G.'s cuts.

He's clearly impressed. "This stuff is sounding good," he says with an approving nod as "Once a Playaz Gone..." blasts from the stereo.

As the music plays, though, he stresses the difficulties Weisner, Black, and the others will face in getting the record out. With P.G. dead, he's not sure it will have much chance of provoking interest from an established record label. "It's hard to market someone who ain't here no more," he says. Still, he likes it so much, he suggests that Weisner get in touch with him. He'd consider putting one of the cuts on a compilation CD project he's working on; he'd "like to give them some love" in his magazine.

"I could see this record totally blowing up," contends Franklin Soults, a Cleveland-based music writer who has written for numerous publications including Rolling Stone, and who currently writes for the Boston Phoenix. He's extremely enthusiastic about the CD, but how much of that is because he knows the rapper is dead? He's not sure. So much successful rap is built on a "beautiful loser mythology," he says, and P.G.'s story is a ready-made myth in the making, one that immediately grabs his attention.

But what really stands out for Soults is how good the record is. He hears innovative and experimental touches on many of the tracks--there's a techno hint to the beats--that's probably born of the eclectic, cross-racial collaborative process that went into their making. "It's probably not that uncommon to find kids out there who were murdered after recording a rap record," he believes, "but it is uncommon to find one who's made a record with such promise."

He says that the same day he listened to P.G.'s disc--three times--he was reviewing two other rap records, by Styles and Project Pat, both out on big labels. "As far as intrinsic musical value goes, this demo blows away either of those," he tells me.

Soults feels the record has a serious possibility of generating major-label interest, and P.G.'s death is not an obstacle. Of course, even if P.G.'s record does get label support, there's no guarantee that it will ever break big, he cautions. The talent is there, but with "an unknown quantity" like P.G., the odds are stacked against it. "Nine times out of 10, with something like this, it doesn't go anywhere," he says.

And Gene Dixon, the vice president of Noc on Wood Records, the million-dollar Seattle-based rap startup label, describes P.G.'s record as a "classic West Coast/Bay Area-inspired... nice street project" that reminds him of a younger version of Nicotena. While he thinks the record would benefit "with fuller music" and heavier beats, he thinks any of the local rap labels would have been interested in learning more about Priceless Game.

Whether P.G.'s record will go anywhere is a question for the future. On Sunday, September 1, P.G.'s friends have more immediate concerns. As the afternoon wears on, a series of rappers, black and white--Enrique Black, Joe Stuhff, Doe Mackin, Rich Weisner--enter the cramped studio one after the other to record their tributes. Black's is particularly evocative, built on memories of friendship and childhood innocence: "Two kids without a care in the world, stealing candy from stores, throwing rocks at the girls." Outside, on the driveway, the others stand around, smoking cigarettes and swapping tales about the friend they'll never hang with again.

Click to download Once a Playaz Gone.

Click to download He Don't Know.

Contact the label at pricelessgamesrecords@ yahoo.com.