I will go on a media fast. For a month, I will not read magazines, newspapers, webzines, or any other regularly updated periodical literature. I will watch no TV, see no movies, listen to no radio. I will allow myself to read only books and listen to only CDs. I will get all my information about the world from conversations with others or from personal experience. -- MY VOW

----I had the idea that by placing everything I would normally waste much of my day reading in a stack in my apartment, I would be able to clear my head, reconnect with my actual interests, simplify my life, and have some quiet time with whatever it is nonbelievers have instead of souls. In short, I hoped to do with a one-month media fast what most people accomplish by dropping out of society and joining a commune or a spiritual order. It was a simple goal, summed up by David Shenk, whom I interviewed last year about five seconds before he turned into a dorky TV pundit supposedly representing my age group. Following the experiences that led him to write a book called Data Smog, he said, "In general I'm struggling to have offline time; unplug myself. We need some quiet, serene spaces in our lives." He'd turned off his cable connection as a first step.

But me, I was going all the way. My already cableless TV was off, and it would stay that way, despite the temptations of The Simpsons and Sesame Street. I would walk downstairs to my apartment's stoop each morning and pick up The New York Times, just so I could promptly plop it, still polybagged, onto the growing pile next to the TV. Likewise with my subscriptions to The New York Observer, The New Yorker, Harper's, and Playboy. The growing pile would be evidence of both my good will in completing the fast and the sheer quantity of what I was choosing not to absorb.

There are many, many reasons not to read newspapers or watch TV, though I would be suspicious of anyone who didn't. The world is clearly too big to understand by mere reference to one's own life and those of the people around you. Leave off reading the paper, or at least watching some TV news now and again, and you'll wind up getting the information you use to understand the world from the guy sitting on the barstool next to yours, or from the contemporary equivalent: e-mail. You'll be ready to believe that breast cancer is caused by antiperspirant use or that the post office is going to start charging for every e-mail sent. And if something really big and sudden happens, there's a chance you won't get the news in time.

Sometime media-basher James Fallows (former U.S. News and World Report editor and author of Breaking the News: How the Media Undermine American Democracy) told me during a recent interview that he'd enjoyed brief periods of fasting when he was off reporting in faraway corners of the world, but that cutting out the media entirely was "nutty, like the boy in the bubble. Media, broadly defined, is everything you live [with]." It's impossible to completely eliminate outside messages, in other words. And even the lower forms of the media -- say, local TV and radio news -- have their uses. Cut them out entirely, and "you're not going to learn that a tornado is going to hit your house."

He's right, of course, but I don't live in a region known for tornadoes, and when the big earthquake hits or Mount Rainier erupts, it'll probably happen so fast that failing to watch Q13 at 10:00 won't matter anyway.

So I figured I'd survive without it all for a month. And that's the surprise. I did. Easily. Going media-free didn't really make much of a difference; I got the basic outlines of how things in the world were going from friends and co-workers. In fact, I can count the notable drawbacks on one hand. One, I didn't know what my mutual fund balances were. Two, I had no idea how my favorite sports teams were doing. Three, I read the front page headlines of every newspaper I saw in a sidewalk box, a frustrating sign of my lack of discipline and reliance on media. Four, when I saw a headline about a major event -- police chief resigning after the WTO debacle, Space Needle almost getting blown up -- I couldn't read about it. Five, when writing an article for work, I had no idea if what I was opining on had already been exhaustively covered elsewhere.

It only took three weeks to realize that my attempt to live a better life, media-free, was a failure. I noticed little in the way of time savings, increased attention span, or reduced distractions. The world was still hyperstimulating, confusing, and full of messages everywhere. I didn't feel more connected with actual lived life, and I didn't finish any long books (I made a good start on three of them). As usual, I more or less kept up with the gushing flow of obligations, let a few slip past me, and woke up most mornings with the abstract dread caused by not having a full idea of what was important to accomplish that day, but knowing the list was long. In a way, I was even less shielded from the world's distractions than before, when I could at least stop time for brief moments by skimming through magazines. Without that small refuge, my hyperstimulated attention was continually being drawn to new focus points.

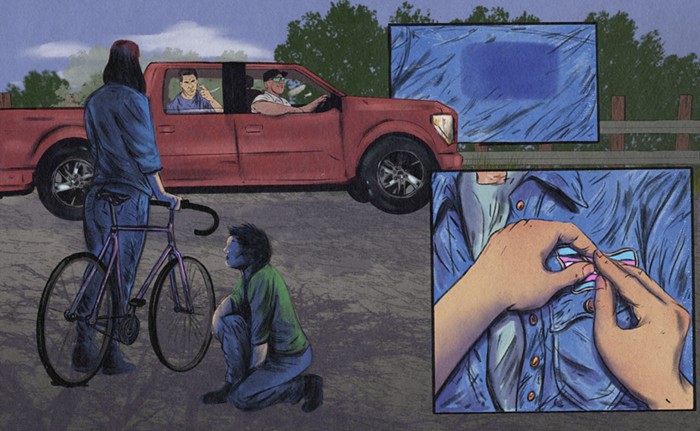

The central metaphor for this distracting buzz is the billboard, the quickly understood messages that pervade our landscape. The techniques of the billboard are replicated everywhere in our environment, on every scale: products on grocery store shelves, newspaper headlines as viewed through vending-machine windows, bumper stickers, overheard conversations, street signs, shop signs -- all billboards. All designed to attract my glance or my ear.

I think I've adapted to this environment in such a complete manner that I will artificially create it during the brief stretches of time when it's not around me. For example, I'm speed-typing this article on a computer, pausing frequently to check my e-mail, and with Eric Dolphy blasting on a stereo. Surely a medieval monk couldn't have worked under the conditions I voluntarily subject myself to -- and probably would be writing something better than what I'm writing as a result of his isolation. But just as surely, I couldn't work without the confusion and noise. Put me in David Mamet's unwired cabin with his manual typewriter, and I'd go blank. And what would I do if I got stuck -- go for a walk in the woods? A fish needs water to filter oxygen from; I need my binging e-mail in-box.

Has my brain become wired to work best in a noisy, distraction-filled environment? Do I, in some way, require it? Evolutionary psychologists have speculated that our tendency to get distracted easily is an atavistic trait, an adaptation from when our survival was more directly threatened. Deep focus could get you killed if you were too busy working on a cave painting to notice the saber-toothed tiger about to pounce on you. Cats and dogs still jerk when something shifts in a room; why shouldn't we? And we have so much information to take in that could meaningfully affect what we're doing, whether it's reading road signs while driving or searching for the labels of our favorite brands while pushing a cart through a grocery store, that we kind of have to be the way we are. We wouldn't want to speed, miss our exit, or go home with granola because we couldn't find the muesli.

When I need to know something about how my brain works, I call my friend Brian, who studies the neuroscience of hearing at New York University. Brian pointed me to an article by Joseph LeDoux, an NYU neuroscientist seeking a biological understanding of our emotions. LeDoux discovered a neuroanatomical pathway that circumvents the cortex, causing us to flinch at a potential threat -- say, a stick that might be a snake -- before we've even thought about why we should flinch, before the concept of "stick" or "snake" has formed in our brains. The cortex then swoops in to dampen the hubbub by processing the available stimuli. But the interesting thing for me is the flinch.

When it comes to visual perception, according to Brian, "It's pretty much a given that we evolved to process the kind of stimuli our environment presented." As an example, our ability to interpret different colors works best when we're looking at a color range equivalent to that of leaves in a forest canopy. How different is the teeming mediascape or the streetscape of billboards and shop signs from that of a forest canopy? The visual complexity may be equivalent, but our relationship to our environment has changed. Living as hunter-gatherers, we needed to look for food and avoid predators. Walking down Broadway, the equations are much more complex than "Dick's Drive-In: approach; creepy person: avoid." Because media is everywhere, the number of stimuli with significance to us seems to be much greater.

Physical evolution takes time, while our environment can change incredibly rapidly. Though we can't change fast enough to evolve into a better relationship with our environment, our individual brains can habituate themselves to certain stimuli, often very quickly. If I suddenly yell "boo" at you, you might flinch. If I yell "boo" 20 times over the course of 10 minutes, you assuredly won't flinch at the 20th "boo." Marketers and media people know this, so they up the ante. They crank the volume on the television commercial. They toss in more images. They add music. And even though we know we're being manipulated, we look up when the Mountain Dew jingle kicks in.

If habituation can't save us from the attention-getting methods of TV commercials, it's likely that it can't save us from the burgeoning amounts of environmental stimuli, either. Try as I might to walk down the street thinking about, oh, the media, a slew of sensory perceptions will pop off little synaptical spike trails in my head before my cortex can step in to tell me, "That's Dick's Drive-In. You're not hungry. That's Cellophane Square. You own enough records." The process is similar amid the mediascape. If my computer can quickly access 10 different media sites, if the space between me and the book I'm planning to read is full of magazines with attractive logos and pretty people on their covers, my attention is sure to be drawn, even if momentarily, from its original goal.

An interesting article on this topic was published on the opinion page of the Sunday New York Times, December 27, 1998 -- probably the slowest news day of the year, and thus well suited for a long thumbsucker: Richard Ford's "Our Moments Have All Been Seized." Ford concerns himself in the piece with the notion that "now" doesn't belong to us anymore, mostly because each "now" is treated with so little respect, and is so quickly interrupted by a phone call, the dinging of an e-mail in-box, or some other distraction. If the world values any one "now" so little, and is so ready to replace it with a series of other "nows," then something big -- on the order of God or the soul or the spirit -- has been lost. His idea of what's being forfeited is represented by the novel, which requires long periods of real-world time to read and concentrate on. Fitting, since he's a novelist. But what is this novelistic idea of the "now," and does it have anything to do with the contemporary world? At least in Ford's conception, it seems like that monk's cell, like David Mamet's cabin: an interesting anachronism that I can't imagine consigning myself to.

I set out at the beginning of this fast to search for the kind of immersive, rich, undistracted experience Ford finds in the reading of a novel. But now, that kind of experience looks like a place apart, a retreat from the messy world instead of a closer encounter with it -- like heaven, or utopia; abstract models, neither of which tend to be very useful for understanding actual life. So instead of entering a novel, I find myself entering the city, where my moments are all seized, certainly, but where "now" could not be more real.

Using the city to locate the "now" is exactly how the 19th-century poet Charles Baudelaire and the 20th-century cultural critic Walter Benjamin found it (though, of course, my street is far uglier than their Paris, the distraction of a mirrored arcade replaced by that of a gas station sign). On my street, I'm distracted by the "now" itself, by what's changed and what's stayed the same since the last time I was out. My distraction finds its home, a place where it's useful -- hey, I might have to dodge a falling piano! Then I can go back home, head cleared, and tackle that mound of reading that's been patiently awaiting my return. Or I could throw it all away -- what difference would it make? I know that I can find its vital distractions anywhere.