At the Seattle City Council's annual retreat last Friday, January 30, council members and their staff broke up into small groups at Discovery Park's visitor center to come up with their tentative 2004 priorities. The "brainstorming" sessions--the first step in the council's "strategic planning" process--will be followed by six "community days," at which council members will "visit with shoppers and shopkeepers, walk through the communities," and hold community workshops. Council president Jan Drago (channeling Utne magazine, perhaps) dubbed the workshops "Conversation Cafes." The council will reconvene three weeks later to formally set its 2004 priorities.

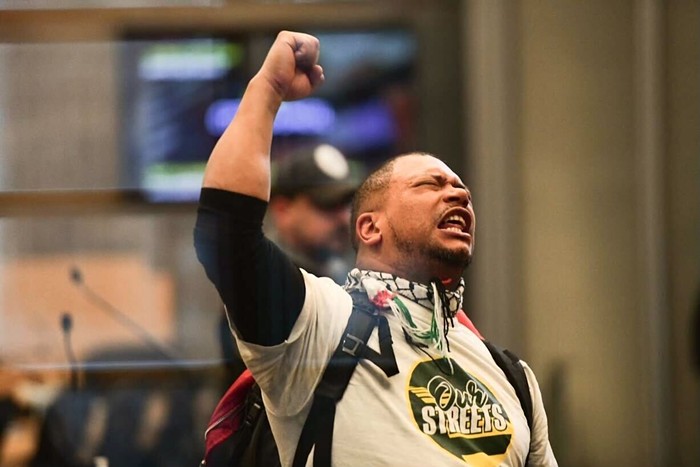

Mayor Greg Nickels, in his February 2 annual State of the City speech (just three days after the council retreat), revealed a vastly different approach to policymaking. Speaking before a packed council chambers, Nickels laid out a concrete 2004 agenda, including specific legislation he wants the council to pass. Nickels' speech, in contrast to the no-agenda council's warm and fuzzy "community dialogues," revealed just how vulnerable to Team Nickels Drago and the council truly are. While the council spends February hanging out in restaurants and coffee shops, Nickels will be taking action.

As Nickels did during last year's State of the City (when he demanded that council members lift the lease lid at the UW--which they subsequently did), and as he did in his budget speech last September (when he demanded that council members pass his Northgate development plan--which they subsequently did), Nickels made a few demands this year as well.

First, Nickels unveiled a plan to increase density downtown and in surrounding neighborhoods such as the Denny Triangle by raising building heights and offering incentives to developers. Then, in an attempt to counter his image as a mayor who kisses up to deep-pocketed developers and white-collar biotechies, Nickels turned all populist. "We've made a great start with biotechnology jobs, but let's... work to create jobs in all areas that pay living wages." He then "urged" council members to approve legislation he sent them a week and a half earlier--giving Nucor, a steel company in Delridge, a break on its Seattle City Light rates to help the company preserve blue-collar jobs.

Council members like Nick Licata are poised to respond to Nickels' agenda by putting the reins on his proposed Nucor giveaway, which was developed without any council input. As for Nickels' plan to increase urban density, Licata likes it, but says more work needs to be done to include low-income housing in the mix.

Licata's impulse to challenge and tweak Nickels' agenda is a solid rejoinder to a mayor with a long history of ramming his priorities through council chambers. The problem is, Licata's response is just that: a response. While the council is busy setting tentative priorities and holding community workshops, Nickels is setting the council's agenda, by sending legislation down and forcing council members to react.

The contrast between Nickels' forthright style and the council's tentative approach was highlighted at the council retreat, where, in the claustrophobic confines of a cramped meeting room at Discovery Park, the council sat studiously in stiff plastic chairs, downing a carb-laden breakfast of bagels and muffins as UW consultant David Harrison schooled them on the finer points of "priority development." It took several dozen bagels, about 10 containers of lukewarm Seattle's Best Coffee, a QFC deli counter's worth of assorted cold cuts, and several boxes of Diet Coke, but the council did, after nearly eight hours, arrive at a list of "tentative priorities." The verdict? The council should focus on creating a "sustainable budget," promoting economic development, improving its relationship with the public, reaching out to other government bodies, and promoting what it calls "social stewardship," which apparently encompasses everything from preserving the physical environment to promoting affordable housing.

Worthy goals, to be sure. But what will the community think? For that, the council is going straight to the source, holding a series of six "community days" throughout February to gauge the level of neighborhood support for its provisional priorities. (The "community days," in which two or more council members will hang out in a neighborhood, will lead to a second council retreat where a final--though not comprehensive--list of priorities will emerge.)

If the January 30 council retreat sounds like it was grueling, well--you should have been there. While facilitator Harrison deserves credit for keeping the council on track (a debate about the city's mission statement, which threatened to absorb most of the morning, being one notable exception), it's unclear what all this dialoguing and coffee klatching and community kvetching will ultimately produce. As one exasperated council staffer muttered after the retreat, "I don't know what these [community] meetings are supposed to accomplish. All they're going to say is, 'Give us more money and don't cut our programs,'"

The council's discussions did include a few solid proposals, although the two most concrete suggestions--from newcomer Tom Rasmussen, who showed up at the retreat armed with an arsenal of charts and press releases--were ready to go before the meeting began. The first would cut the cost of Seattle's health care system by allowing the city to import inexpensive drugs from Canada; the second would create a record-keeping system to track the city's performance at providing services. Although council members seemed receptive to Rasmussen's proposals, nothing they suggested at the retreat remotely resembled the kind of concrete plan the council will need to provide a check on the mayor's agenda. The most telling moment at the retreat: Given an explicit opportunity to discuss mayor-council relations, the council's "working group on external and internal relations," demurred, putting the issue off until February 19.