This past December, the indie-pop and prog-rock sleuths of Mt. St. Helens Vietnam Band ventured up into the gray maw of Anacortes to record in a church. The church, now a music studio called the Unknown, was at one point a sail-making shop. Without pews, the sanctuary auditorium is cavernous—large enough to create sails. The acoustics are expansive, as is the natural reverb. For the better part of a year, MSHVB had been removed on sabbatical, taking time off to let the group regroup from two years of touring and member shifts, and to write new material. The road had run them ragged.

The end result of the Unknown Anacortes sessions is an EP called Prehistory. It's a confession-filled collection of simple, coherent ideas, recorded mostly live. Guitar amps were placed in the church's confession booth. "The songs are about untangling and extricating yourself from unreal expectations and finding connections with worthwhile things," says singer, guitarist, songwriter Benjamin Verdoes. "Pressures had mounted. We were sapped. The business of music had evaporated the enjoyment of playing music. I almost had a nervous breakdown and needed time away. So I moved to San Francisco for the summer to reconfigure. I think now I know enough not to care about the imaginary world of success."

Benjamin Verdoes functions as the legal guardian of the band's 17-year-old drummer, Marshall Verdoes. Benjamin is Marshall's father, brother, bandmate, and friend. While touring, he raises him in a van, city to city, on little to no budget, teaching him school and trying to instill what's wrong and right amid a makeshift mobile structure. Like most teenagers, Marshall is attention-challenged. Neither Marshall nor Benjamin had a father figure. Benjamin's father, a Vietnam vet, died of a heroin overdose. Benjamin's mother had adopted Marshall, and when she became unfit to raise him, Benjamin stepped in. The bond between the two is extremely close.

"The best way to love me," says Benjamin, "is to love Marshall. He's the most important thing in my life. The main reason I want MSHVB to do well is so he can play shows all around the world. I want him to see the world."

For his part, Marshall says: "I like the dynamic with Benjamin. It's hard sometimes. He keeps me in check. Who knows what I'd be doing without him. I appreciate him, except when he's disciplining me. He's always on my ass about something!" He laughs. "But he's family, and I love him. I'm proud of these songs."

The band became Benjamin's way of giving Marshall something to base a positive sense of self on. "I've been playing with him since he was 8. Drumming is what he is here to do. It's hard raising him, but I wouldn't change a thing. Marshall amazes me the more I get to know him. He's amazing."

Toward the end of MSHVB's initial run, Benjamin and band keyboardist Traci Eggleston, whom he had been married to for four years, divorced. Since Eggleston had become a mother figure to Marshall, the breakup and her subsequent departure from the band were sensitive issues. Add to the mix Benjamin's sickly mother, who passed away this winter, a booking agent who was threatening to drop them, and somewhat disappointing reviews for their second album, Where the Messengers Meet.

"The criticism about us was hard," says Benjamin. "The band is such a central part of our lives. It's this extremely personal thing—my connection to Marshall, Jared Price [bass], and Drew Fitchette [guitar]. What we do and have isn't really made to be judged. Vying for some critic's approval isn't why we make music. Press and reviews won't make or break us. I don't want anything to do with a business model. That robs the soul. It makes success feel like it's tangible, makes art feel like a giant competition. Ultimately it becomes less about writing good songs and more about making money. I think I've learned to accept all of it for what it is. To enjoy the existence of it all. I don't want to understand the mechanism. Hope looks different than most people think."

Prehistory shows a band that's transitioned, has evolved, and is healthier. This is their second chapter. Benjamin isn't teaching Marshall the music anymore; the man-child drummer has been let loose. His drums were on the stage in the church where the pulpit goes. The beats felt preached, slung out of his musket arms. Where the congregation would have been, 50 feet away, were Benjamin, Jared, and Drew. No click tracks were used for the recording. The songs respire and surge more straightforwardly than previous album signatures in seven and five.

"I wanted it to be live because I wanted us to show that we are a band," Benjamin adds. "I think live recording forces a sense of honesty." Trevor Spencer, an engineer and producer who had worked with Fleet Foxes, had access to the church in Anacortes. MSHVB's Fitchette showed him some of the songs, and recording at the Unknown seemed like the natural thing to do. "I have to mention the Foxes' generosity," says Spencer. "Because my experience running their in-ear monitors was life-changing, and they sugar-daddied the hell out of my gear stock, including a 24-track tape machine." Spencer continues, "MSHVB were tracked almost completely live, sans vocals and some overdubs, to a 16-track one-inch tape machine. That's an important part of the sound right there."

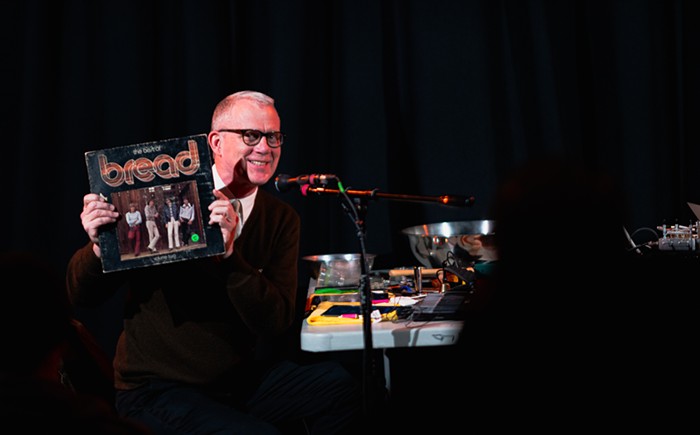

The songs on Prehistory sound like a band coiled back, ready to rear its new face. "We Won't Change" mounts and charges on a direct line. "Warm Body" is acoustic and forlorn. Benjamin warmly detaches. With it he sheds some of the pressures, singing in tempered observance: "They tell you to be free, but they hate the thing you want to be/And they tell you to be brave, as they point their fingers at your grave/I'm just a warm body now, but I love you." Talking about this new sound, Benjamin says, "It's us being ready again, enjoying it again. It's the goodness of life creeping back in." ![]()

This article has been updated since its original publication.