In 2003, I took my best friend to see Swan Lake at Pacific Northwest Ballet. During the second act, she suddenly developed such a bad case of restless leg syndrome that we had to leave during intermission. The RLS never resurfaced. In 2007, I took a very sexy artist boyfriend to see the same staging of Swan Lake, thinking he'd be impressed by Ming Cho Lee's slyly discombobulating sets. The artist-boyfriend texted his way through the first act and then suggested in a loud whisper that we go back to the U-District for a drink. Over the past several years, I've taken four nondancers to see Swan Lake, and not a single one has made it through the whole thing.

And now that's what those people think dance performance is—a long, drawn-out, convoluted story communicated through archaic and repetitive aesthetics, interspersed with overpriced, mediocre glasses of pinot gris and long lines for the bathroom. For most ballet virgins, Swan Lake is regarded as the ballet—it's the one they've heard of, the one Hollywood makes movies about, the one people flock to, and the one companies like PNB serially produce. When people want to give ballet a try, that's what they tend to go see.

And that's a problem—I may have screwed those four friends out of ever wanting to see dance again. Die-hard dance fans (like me) enjoy Swan Lake for other reasons. In some ways, it is a pinnacle of dance athleticism. But it is undeniably tedious, older than dirt, and pretty goddamned boring.

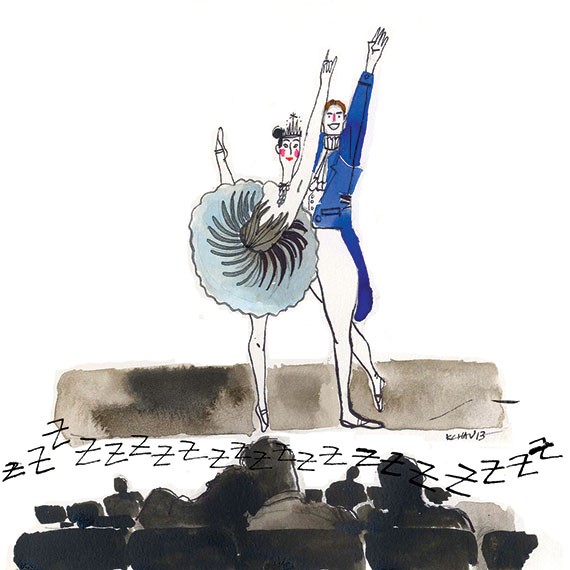

Swan Lake premiered in 1877. The story is simplistic and sexist, but, like traveling exhibits of the French impressionists and seasonal performances of Handel's Messiah, it's been filling arts palaces around the world for decades. This is weird—cities like Seattle, New York, Boise, and Paris are oozing amazing talent and brilliant new choreographers (Seattle's Amy O'Neal and Jason Ohlberg, Boise's Trey McIntyre) who meld tradition with invention and have thrilling new styles and ideas. And yet, for the eleventh time in the last three decades, PNB will pack a performance hall with spectators paying good money to see a four-act, three-hour ballet about cursed love, royal duty, and zzzzzz...

I loathe Swan Lake for the damage it's done to popular perceptions of dance, but I'll never tell someone not to go see it. From a dancer's perspective (I have a deep, dark past as a bona fide bunhead), it's fucking badass. The ballerina has to play two characters: One is sweet and passive (the heroine!); the other is an evil whore who lies and bullies her way into a private party to get in the pants of the rich prince (the bitch!). To alternately and convincingly pull off those two roles over the course of four acts requires a degree of artistic maturity that many professionals never achieve.

The choreography has some major challenges, including a series of 32 fouettés—a ballet step that I won't even try to describe here other than to say it's a single-footed turn that you couldn't complete once in your wildest, wettest Baryshnikov fantasies—and 24 corps de ballet members standing stock-still with mournful expressions for minutes on end. Try that for 30 seconds without getting the giggles or scratching your butt. Swan Lake is like a marathon for ballet dancers. Performing it earns major street cred, but watching it can be a major drag.

To someone who's not deeply familiar with classical ballet, its choreography (including the boner-inducing fouettés) hasn't changed much since the premiere. This isn't random—classical ballets are frequently based on the choreography of the masters who originally set them (in this case, the Russian granddaddies of ballet choreography, Marius Petipa and his student Lev Ivanov). The choreography and staging of PNB's production comes from the scary-smart brains of former PNB artistic directors Francia Russell and Kent Stowell, who weave their artistic perspectives with the original swanlike movements, classical ballet formula, and demands of a modern audience. When Swan Lake was first produced, it wasn't common for ballerinas to extend their legs up to their eyeballs or for men to jump 10 feet off the ground. But ballet technique, like the bodies that perform it, evolves, and the choreography must be able to show off all the expected tricks. That choreographic revision has to be done well or it looks like shit.

The Russell/Stowell team know what they're doing when it comes to perfecting classical ballet for the modern stage—in an interview last week, Stowell claimed their 1981 staging of Swan Lake brought PNB into the national spotlight—and they both trained and performed under New York City Ballet master George Balanchine, who is widely credited with establishing and shaping American ballet culture as we know it today. However, there's a good amount of work in the Russell/Stowell repertoire that is far sexier—Carmina Burana, for example—so why does Swan Lake remain such a blockbuster year after year? According to Gary Tucker of PNB, with the exception of the annual Nutcracker performances, the company loses money on every production. While Swan Lake is by far the most successful of these losses—other shows sell between 3,000 and 5,000 tickets, while Swan Lake sells upwards of 20,000, including subscriber attendance—it's not raking in dough. (Tucker added the company hopes to make $850,000 on this year's show just to break even.)

Do people simply want to know what to expect, so they save their art-consumer dollars for Swan Lake, Nutcracker, A Christmas Carol, and Monet, no matter how predictable and drab they might be? Is it the magic of Tchaikovsky's score? His music is pleasant and comforting, no doubt—Tchaikovsky's scores were made for dancing, and he had specific moods and movements in mind, so there is a built-in fluidity from sound to movement that makes for a natural (Boise-based choreographer Trey McIntyre would say "lazy") flow of choreography. Or is it just the romantic legends behind the story, including one in which Tchaikovsky wrote Swan Lake after visiting the castles of swan-obsessed Crazy King Ludwig, who went "swan hunting" at night with a boyfriend and wound up mysteriously dead in a murky German lake?

Maybe people just love the familiar. It's why we buy DVDs of our favorite movies, see our favorite bands when they play in town—we love what we love, and there's nothing much wrong with that. Right? Maybe? Tucker Cholvin, a young college student who became entranced with PNB productions through Teen Tix (a Seattle initiative to make arts events affordable for teenagers), explained his multiple high-school trips to Swan Lake by drawing lines between his love of the music ("It's timeless," he said, "it's awesome. It's kind of written on the inside of my skull!") and his mother's habit of playing it every time she cleaned the house. But Cholvin used this love of Swan Lake to propel his exploration of other dance, and he realized that Swan Lake wasn't the be-all and end-all. Cholvin likens the popularity of Swan Lake to the metaphor of the shitty cupcake: People will line up around the block for a lame, dry-ass cupcake from a bakery that won Cupcake Wars on the Food Network, while down the street, killer cupcakes go stale without the props of a cable competition to proclaim their deliciousness. Until the public steps out of its comfort zone a little bit, quality and innovation won't win.

Seattle is a young city with a lot of rich young people, and organizations like PNB have a responsibility to push the dance-going public to see new things and support newer, progressive choreographers. Sometimes they do, with world premieres and even more contemporary work since artistic directors Stowell and Russell handed the reins over to national dance star Peter Boal. But some of us—and our dance-virgin friends—can feel a little cranky when we see that PR machine heat up for yet another fucking Swan Lake. ![]()