President Medvedev has signed a law—backed by Dear Leader Putin—that abolishes jury trials for "crimes against the state," softening the ground for full-scale political purges. From the LA Times:

The law does away with jury trials for a range of offenses, leaving people accused of treason, revolt, sabotage, espionage or terrorism at the mercy of three judges rather than a panel of peers. Critics say the law is dangerous because judges in Russia are vulnerable to manipulation and intimidation by the government.A parallel piece of legislation, pushed by Russian Prime Minister Vladimir V. Putin and still awaiting discussion in parliament, seeks to expand the legal definition of treason to such a degree that observers fear that anybody who criticizes the government could be rounded up by police — and, because of the law signed Wednesday, tried without jury.

The government has framed the jury law as an anti-terrorism measure, but legal experts warn its implications are broader and more ominous — especially if the treason changes go through.

Sounds like one of Naomi Klein's Wolf's [UPDATE: Brendan Kiley regrets the error; last night's revelry is no excuse for moronism] more paranoid fantasies circa three months ago—but it's real, and it's in Russia.

This, an expert in the article noted, isn't a sequel to the grand, sweeping terror of the Stalin years but a more targeted and intimate form of terror, closer to the Dirty Wars of Chile and Colombia.

From "Terror as Usual" a 1988 essay by the brilliant, Australian doctor-turned-anthropologist Michael Taussig:

Above all the Dirty War is a war of silencing. There is no officially declared war. No prisoners. No torture. No disappearing. Just silence consuming terror's talk for the main part, scaring people into saying nothing in public that could be construed as critical of the Armed Forces. This is more that the production of silence. It is silencing, which is quite different. For now the not-said acquires significance and a specific confusion befogs the spaces of the public sphere, which is where the action is.

Find a copy if you can (there's a limited preview version here).

It suffers from occasional fruity-academic-speak ("Terror as The Other" is a little nauseating, but give the guy a break; what were you writing in 1988?). Otherwise, it braces and frightens, swooping from a conference where tennis-playing academics blithely discuss mass murder in Latin America to the jungles of Columbia, haunted by death squads and eerie croaking frogs, to ruminations on Walter Benjamin's theory of history as a permanent "state of emergency."

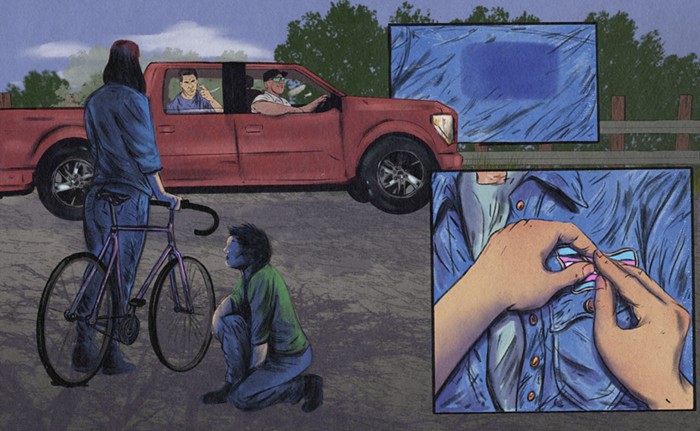

In the final section, it turns into a true thriller, as Taussig meets a "disappeared" man at a hideout apartment in Bogotá for an interview about the Dirty War:

... he left without a word, the locks grating—all four of them—leaving me alone in the white cage whose door was reinforced on the inside by heavy gauge wire mesh, also painted white... the fluttering sensation recurred, stronger. I felt I was being set up. I tried to read more but my eyes only flicked over the pages. Not a sound. A few minutes went by. I realized nobody knew where I was other than Roberto. Why hadn't I called Rachel?

The rest of that section hurts to read. I don't want to spoil, so I'll say no more.

With its oppressive new laws, Moscow 2009 might start feeling like Bogotá 1988—especially for people like chess master Garry Kasparov who, after his failed attempt to unseat Putin, is still tilting at the Kremlin:

The organization, called Solidarity after the victorious Polish anti-communist movement, aims to unite the country's dysfunctional liberal forces and encourage a popular revolution similar to that seen in other ex-Soviet countries."We are fighting for victory because we have something to say to our people and something to offer them," Kasparov said at the founding congress Saturday in a Moscow-region hotel. "On this very day, we are in a position to take stock of past mistakes and act differently," he said.

But in a sign of what it may be up against, members of the pro-Kremlin youth group Young Russia, some dressed as monkeys, demonstrated outside the Saturday conference, distributing flyers that read "monkeys are rocking the boat."

Standing around a wooden dinghy, they hurled bananas into the air, some of which were lit on fire.

God save the brave—is there a good NGO or organization fighting for Russian democracy a person could donate to? Seems like a good way to start the new year.

In the meantime, buy a copy of Taussig's The Nervous System—essays about toad infestations, jungle witchcraft, and theory—for someone you love.