w/Soviet, Cobra High

Wed Nov 20, Graceland, $10.

I divide keyboard-driven music into two types: smart or sexy. Most of the stuff on Thrill Jockey or Kranky is smart; I don't like it--it sounds sterile, and it doesn't make me hot. England's Add N to (X), however, makes me hotter than if I skipped across Hell in gasoline-soaked underpants.

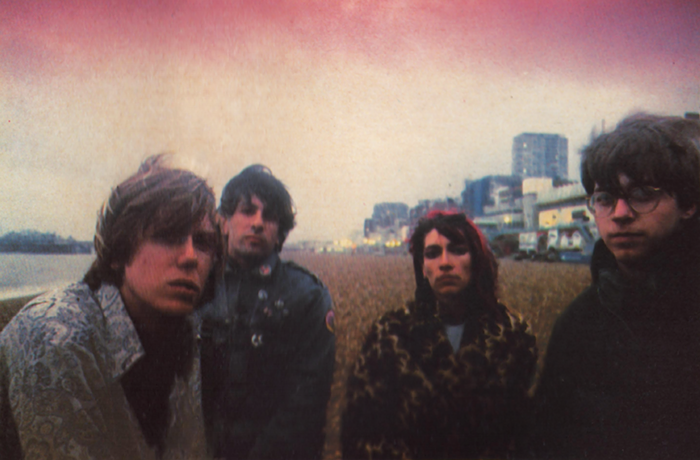

Their newest record, Loud Like Nature, is sexy, slinky-hipped rock created by a trio (Barry 7, Steve Claydon, and Ann Shenton) who'd sooner die than create sterile synth pop. This is their fourth album, and leader Barry 7 knows it's sexy as hell, even if those in his homeland, England, don't. "I've had a lot of Americans say the album is sexy, but in England, it's just not. It's really over for us there; we're too strange. In the U.S. people know who Kim Fowley is [songwriter for the Byrds, the Beach Boys, Them; creator of the Runaways] and that there's no reason why we shouldn't try to mash up different styles. In England if you're too schizophrenic and messy you're unacceptable. They much prefer an album of tracks that sound exactly the same and have the same tempo, like Coldplay, for instance. The whole thing is miserable."

One aspect that separates Add N to (X) from other keyboard-driven bands is that they use a live drummer (on this tour it's Joe Dilworth, formerly of Stereolab and Faith Healers). Is that what makes it hot? "Possibly," Barry ponders, "I think so. There is a kind of sleaziness to it, you know? I think you could strip to it quite happily and that's probably the plan. But I've never stripped to it, thank God, because it would be a very ugly sight."

The members of Add N to (X) are like scientists seeking new uses from old materials. The music expands with each album, which Barry calls "a motif." "What we've always wanted is a kind of multidimensional mind. It's not a mind that's about progressive invention. It's like you're building this really strange city and through the centuries things keep getting odder and odder--you put in weird transport systems and the routes are like being inside a pinball machine."

It's not as haphazard as it sounds, though. "There's always a visual picture first," continues Barry, "then the music comes after because we don't think like musicians. It's like Frankenstein. All these body parts stuck together. Our first album ['98's On the Wires of Our Nerves], our surgery was pretty shit. We could see all the stitches and we've got the leg on the arm and the arm on the leg. But now our surgery is fucking great. It's almost like the last album [2000's Add Insult to Injury] is Frankenstein and the new one is the Bride of Frankenstein. We got the hair right this time. It's a cut-and-paste project but we're not interested in technology."

Not interested in technology? What?

"No, we're not into it at all," responds Barry. "I think a lot of electronic music focuses on the newest equipment on the market. Using old gear is more like an investigation into what these endless machines can do. I felt shortchanged by bands like Kraftwerk and Cabaret Voltaire when they ditched their great equipment and went digital. I thought it was a cop-out on machines that deserve to be studied deeper."

I ask Barry if he's saying there's no limitation to vintage equipment. "For a start, I don't think of anything as vintage," explains Barry. "Like if you find a second-hand record, it's relevant to you now. You found it, so therefore it's current. You're investing in obsolescence. When we first found all of these machines, they were obsolete. Nobody wanted them because they were completely irrelevant and redundant based on the technology that was coming out on the market. A guy in his garage, a single mad inventor, invented these old things. They are there for you to discover what was in this inventor's mind--why he decided to put together all the circuit boards in order to make all of these kinds of sounds. These machines have all sorts of strange symbols and knobs and dials, and you become the scientist."

For those interested, Barry's favorite machine is the ARP2600, which he calls "brilliant." "I've always loved keyboards more than guitars," he says. "I think a keyboard has the ability to transport you and force you to imagine. We use them to create riffs that set the atmosphere, whether it's a murderous one or a punk one. We much prefer that than a jaunty, sing-alongy keyboard line. We do all our experiments in the studio and then when we come to play it live it's like rock and roll, supercharged, and that, for us, is the excitement."