Bobby Bare Jr.

w/Gerald Collier

Sun Nov 17, Tractor, 9 pm, $8.

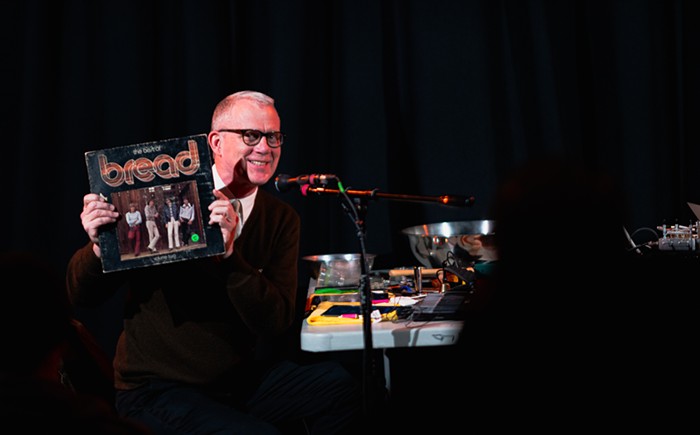

It's commonly assumed that Bobby Bare Jr. is a country musician. It's an understandable presumption, considering the influences of genetics and geography. His dad is country legend Bobby Bare, and his childhood home in Nashville, Tennessee, was a regular congregation spot for Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and many members of the Cash family. He was even nominated for a Grammy for Best Country Duet at the tender age of five ("The goddamned Pointer Sisters beat us!" he recalls with bemusement). Despite those facts, Bare--as frontman for his band Bare Jr. and most recently as a solo artist--is a full-tilt American rocker whose reckless bravado and preference for blistering volume are more reminiscent of a young Tom Petty or Paul Westerberg than anything typically associated with Nashville.

"I open my mouth and I have a Southern accent, so if people have the need to categorize me, that's fine," says Bare via cell from his perpetually touring van. "But it's hard for me to think of my stuff as having anything to do with country music."

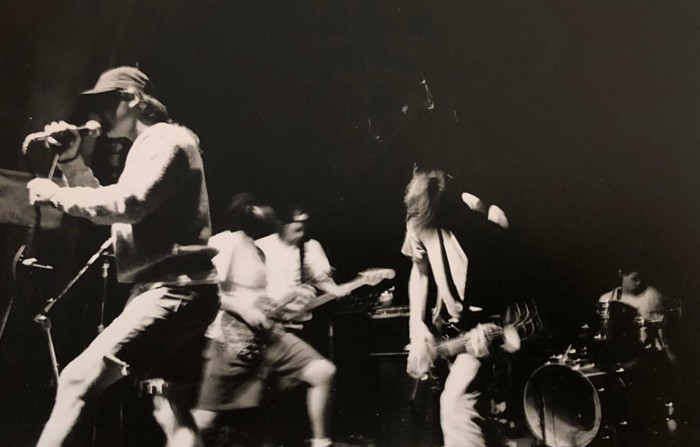

There was certainly no sign of warble or twang on Bare Jr.'s 1998 debut, Boo-Tay, a brash, solipsistic collection of clever ruminations on unrequited lust that shuddered with Bare's hoarse-throated classic-rock vocals and vicious shots of Southern-fried guitar and distorted dulcimer. The muscle of Immortal Records got the band some mainstream airplay and opening slots on Aerosmith and Black Crowes tours, and helped finance their bizarre and boisterous follow-up, Brainwasher. Produced by Paul David Hager and Sean Slade (Radiohead, Hole), Brainwasher celebrated the ridiculous philosophies road-weary musicians accumulate after years of touring ("They pay us with beer/we stole all this gear/so why do I need a job?") and echoed with Bare's running lament that he can't keep a girlfriend.

Despite his self-professed girl troubles, both albums also showed off Bare's larger talent for writing in the voices of female characters. "I just think about girls a lot--I want to know what they're really feeling, and I tend to romanticize that," he drawls, somewhat bashfully. Much like Tom Petty vividly painting from the perspectives of American girls who would listen to their hearts, Bare slipped believably into the skins of uneasy teen harlots measuring their self-worth by the strength of their flirting skills--and even older women struggling with bad taxes, drug habits, or too much wine.

His sound wasn't country, but his inspiration and ethics were clearly the result of being parented by a rebellious Nashville icon. "I just wanted to be like my daddy," says Bare. "He's on stage singing--everybody thought he was cool, and so did I. A lot of kids look up to their father as some godlike figure, and I was no different." Bare Sr. advised him to beware of the music industry's fickle attention span and stick to his own path. "He taught me not to go chasing after radio and to just do what I want."

What Bare wanted next was Young Criminals' Starvation League, a stripped-down album focusing on his growing songwriting skills--skills honed under the mentorship of family friend Shel Silverstein. "Shel's critiqued every song I've written--up till he died," says Bare softly. "He was very, very supportive."

He honors Silverstein with a cover of "Painting Her Fingernails" (sweetly augmented with backing vocals from Bare Sr.), and also pays homage to another enormous influence, Morrissey, with a cover of the Smiths' "What Difference Does It Make."

"I think he's one of the greatest lyricists ever," enthuses Bare of the Mozzer. "He has to have a sense of humor! 'I smoke because I'm hoping for an early death and I need something to cling to'--that's just funny!"

His love of Morrissey's humor reflects in his own gift for grafting tragedy onto comedy. The protagonist of "Flat Chested Girl from Maynardville" is a miserable, lonely goth girl who "trades her CDs for weed and Ecstasy," screams for someone to tell her she's pretty, and then "kicks her cat into the fan and giggles as he bleeds"--sad, but hilarious. "I think you have to find humor in the pain somehow," affirms Bare. "If you can take your tragedy, bounce it off a room full of people, and get them to laugh about what scares you, then it lightens the load a little."