Tues April 6, Chop Suey, 8 pm, $8.

Electrelane are something of a thinking person's band. Vocalist/keyboardist/saxophonist Verity Susman holds a degree in philosophy from Cambridge. On the quartet's new album, The Power Out, she sings in four languages, and woven into the lyrics are a Friedrich Nietzsche quote, stanzas from British poet Siegfried Sassoon's "A Letter Home," and a sonnet by 16th-century Spaniard Juan Boscán.

So you can just imagine what kind of a field day the UK press--still lusting after shaggy, beanpole garage-monkeys banging out Stones and Stooges riffs--has had with this Brighton bunch.

"Yeah, we've had quite a few people say that we're pretentious," says Susman. "I guess we're the kind of band that's inevitably gonna get that, but I find it annoying because I know I'd never be like, 'Oh, look what I know.' We'd never make something that's elitist or exclusionary in any way. That's rubbish to me."

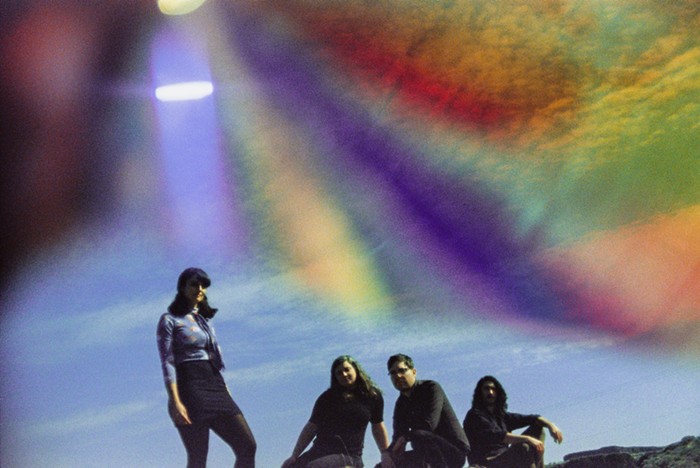

Grievance lodged, Susman sighs and laughs. She and her sisters-in-arms--guitarist Mia Clarke, bassist Rachel Dalley, and drummer Emma Gaze--have been through this before, albeit for entirely different reasons. Electrelane's 2001 debut, Rock It to the Moon, was a virtually all-instrumental, Farfisa-and-guitar-propelled affair teeming with sprawling, overtly cinematic constructions (hell, they named their first single "Film Music"). The album's dynamics earned comparisons to Godspeed You! Black Emperor and Mogwai, which, according to some music writers, meant it was too artsy-fartsy.

But critics be damned, Electrelane got loads of love in indie rock circles (college radio was especially kind) and they bolstered the buzz through two years of touring with the likes of Broadcast, ...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead, Sleater-Kinney, and Le Tigre. Eventually, Steve Albini offered to engineer the follow-up, and as they prepared to enter his Chicago studio, the foursome knew they wanted to steer away from the whole "soundtrack to an imaginary movie" approach.

"Because there was such a big gap between the first album and the second, as a band we were developing into something different," Susman explains. "We were a lot more interested in traditional songwriting structures and clearly defined vocal melodies, and we wanted to see how that would turn out for us. So this record definitely has more of a pop sensibility, although I still consider ourselves an instrumental band because the music always comes first--I add the lyrics later."

True enough, the mere presence of vocals on nearly all of The Power Out's 11 tracks--never mind what tongue they're in--will surprise anyone who's lived with Rock It to the Moon these past couple of years. Even more striking, though, are the mammoth stylistic leaps the band takes from song to song; like a Eurailpass-wielding undergrad, these gals are all over the map. "Gone Under Sea" sports a steady, hypnotic Krautrock pulse akin to prime Stereolab, while the spookily spiritualized "The Valleys" employs a 12-man choir to reach backcountry gospel fervor. "Take the Bit Between Your Teeth" is a twangy, Texas-sized rave-up; "Only One Thing Is Needed" does X-Ray Spex through an electro filter; and "This Deed" plays like the Chills' "Pink Frost" affixed to Simon and Garfunkel's "Scarborough Fair."

"If we'd latched on to one thing we thought really worked, I suppose we would have pursued that over the course of a couple songs," Susman says almost apologetically, unconvinced that the album's diversity is one of its greatest strengths. "But at the same time we always want to experiment and not make two songs that sound exactly the same or two albums that sound the same.

"We had ideas about what we wanted to write, but we didn't necessarily know what the results would be until we started playing and following the music," she continues. "You could be really conscious about it and rehash the typical chord structures that you know will evoke a certain mood, but that's kind of cheap. When you're not conscious of things is when it works. Nietzsche wrote about that in The Birth of Tragedy, being in that whole Dionysian state of dancing and being drunk and tapping into some kind of life force."

Susman pauses, then laughs sheepishly. "We did the album right after I finished up at university, so all of that was really in my head. You could look up the Nietzsche stuff if you wanted to, but honestly it's completely secondary. It doesn't matter as long as you get some kind of feeling from the songs."