When Christian Fulghum and Justin Pinder founded Gyld, they had high hopes it would benefit "emergent independent musicians" in ways that other subscription-based music streaming services have failed to do.

Given their backgrounds in music—Fulghum as a label owner, Pinder as a recording artist—it felt only proper that their upstart enterprise would be founded on principles of artist friendliness. Where Spotify, Tidal, Pandora, and their ilk were parasitic warehouses, Gyld would be more like a cool boutique, curated by musicians instead of algorithms.

It offered artists a 65 percent cut of revenues in exchange for an 18-month exclusive license. Once on Gyld, artists could invite their fans to pay a monthly $5 fee for access to the site's library, which eventually included both exclusive and nonexclusive material. The idea was to get people who've attended shows and bought merchandise to further support their favorite artists through a subscription model.

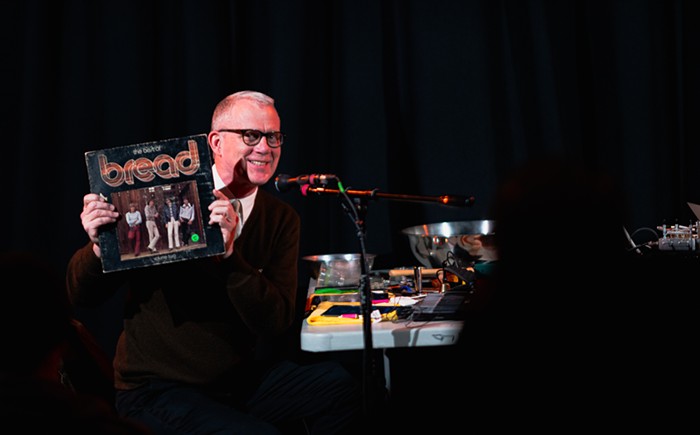

Fulghum and Pinder set about recruiting a smart, diverse team of fellow Seattle music veterans, including Stranger Genius Award winner Steve Fisk, former Chop Suey talent buyer Jodi Ecklund, and renowned hiphop producer Jake One (aka Jacob Dutton), to help recruit contributors. Thig Nat of the Physics was hired to design the website. Thus, Seattle's own music streaming service was born.

Then, after only two months of business, before it even reached the beta stage, it died.

Gyld quietly shut down operations on September 9, leaving most of its employees—and cofounder Pinder—angry and allegedly owed money. According to the disgruntled team, investment funds Fulghum had promised to secure to help launch the company never materialized. The question now is how real the prospect of that money was to begin with, and how honest Fulghum was with his partner and his employees.

"We're still not getting the full story," says Fisk in a phone interview. Though he considers Fulghum "a great friend and someone who's helped me make some wonderful music," Fisk now believes that Fulghum "never had any of the initial seed money that Gyld was going to need to pay everybody and keep the thing going for a year or two. It fell apart from him not paying people, and him not talking to anybody."

Christian Fulghum has not responded to multiple requests to comment for this article.

According to Fisk, Gyld's team would have been patient if Fulghum had chosen to put the company on hiatus while he searched for funds, but that's not how things transpired.

Furthermore, Fisk says he has heard persistent rumors of Fulghum meeting with musicians about Gyld—as if the company still exists. But with no money or employees, Fisk points out, "the Gyld is whatever [Fulghum] says the Gyld is."

Pinder adds, "One of the excuses [Fulghum] gave for his failures is that he was stretched thin and was tired mentally and physically and couldn't contribute in a way that he agreed to," so the reports of these meetings strikes him as "confusing."

With disappointment in his voice, Fisk says, "It was bad enough that Jodi and I talked our friends and associates to be part of this, but now he's still doing that. I want to say, publicly, as far as I can tell it's over with and nobody should quit their day jobs."

"I feel like the Seattle music scene is owed an apology," he adds. "And I would like to offer it on my behalf."

This is not the first time one of Fulghum's music business enterprises has gone up in smoke. Several people who witnessed the dissolution of Fulghum's label, Fin Records, in 2014, confirm that the end also came out of nowhere, without any warning to the artists signed to the label, and with very little communication from Fulghum before or after.

Fisk worked closely with Fin, producing records by the Seacats and David Hahn and doing a handful of remixes for Pinder, a respected rapper who was one of the label's first signings. Before it went under, Fin was to release the last record by Pigeonhed, Fisk's duo with Shawn Smith. "He was the ideal record-company guy," Fisk says of Fulghum. "We got to spend good money on young artists who were new to the studio. He was hands-off. He was a perfect 1980 record-company guy—Tony Wilson," he added, in reference to the beloved founder of Factory Records.

But Factory is as famous for its financial problems as for its hit records, and Fin never had any hit records. Even though Fulghum hadn't been forthcoming about the end of Fin, it's worth noting that both Fisk and Pinder, recording artists for the label, were willing to sign on with him again for Gyld.

Fulghum put out three releases by Pinder and helped him embark on a few tours. Pinder says he was working with Dr. Dre in Los Angeles when label shut down, so he didn't exactly know how it folded, but the Gyld experience lines up with what others had told him to expect.

"It's definitely a trend in behavior from Christian I was aware of," Pinder says. "Ultimately, it comes down to him not being the guy for the role he wants to see himself in. He doesn't quite understand how the music business works, nor does he understand people very well. He's a sweet guy, but I'm starting to feel like that is a front."

"At the very worst," says Fisk, who saw Fin's collapse up close, Fulghum "seemed like someone who would get depressed and need space to himself. I wouldn't call that 'crazy.' I'd call that a logical response to an embarrassing loss—Fin, another sad thing to live down, another great idea [that failed]."

But the current episode strikes him as something worse. "This kind of disconnect is not part of the Christian I know," says Fisk. "He's always seemed like a rational dude." Not all his erstwhile teammates are quite so diplomatic.

"Christian built a company on lies and allowed employees to leave their jobs," writes Ecklund in an e-mail interview. "Ironically, he's the only one of us who still has a job."

Ecklund was hired away from her Chop Suey position to join Gyld's A&R team in the summer of this year. She says she was paid for her work in July and early August. Then the checks started bouncing. "The check I received for the pay period on August 20 was NSF [not sufficient funds]," Ecklund says. "A new check was issued and that was NSF as well. I never received my check that was due on September 5, either."

Four days later, when the site went down, Ecklund was left scrambling for money and looking for work in the city's withering music economy.

"I trusted Christian and considered him a friend and ally to the local music community," Ecklund continues. But "he humiliated me and my peers. I was signing bands up to the service [and] all the while it was just a fabrication of a fictional company he believed was real."

"I guess the moral of the story is: If something feels too good to be true, it probably is," she adds, ruefully.

It's worth noting that whatever you might think about streaming services in general, Gyld was shaping up to be an interesting and Seattle-centric variant on the formula. Fisk notes that he'd convinced the Gits to upload a live show, secured the entire Maktub catalog, and lined up original material from Carrie Akre, Selene Vigil, Master Musicians of Bukkake, Mark Pickerel, and others. He was also in talks with Earth, TAD, and King Missile's Chris Xefos.

The bright side of Gyld's rapid failure, he says, is that it didn't harm any of the artists' release schedules. And Gyld's contract states that if the company failed to fulfill any of its responsibilities, all content reverts to the artists. As frustrating and embarrassing as those dealings now seem, Fisk says that the artists have been understanding and are patiently hoping Gyld can return.

Pinder has a more immediate goal: to resolve what he calls "the cofounder situation"—he says Fulghum has not been cooperative—the better to make Gyld attractive to investors. "I'm owed the company that I built, essentially, with the Gyld team," Pinder says. "It's tough to see your baby on a breathing machine."

Pinder believes that musicians and consumers are clamoring for a service like Gyld and he hopes the company can eventually revamp without Fulghum. "We're trying to detach [Fulghum] from Gyld so it can move forward and do the things it's promised to do," he says. "And while the chances of survival are not great, we're still optimistic."