It's going to be a violent summer. After three years of street shoot-outs sparked by disputes over drug turf, prostitution rackets, and disrespect between rival gangs, the Seattle Police Department is beefing up its gang unit, bringing the unit's total to 15 detectives and three sergeants in preparation for an anticipated street war.

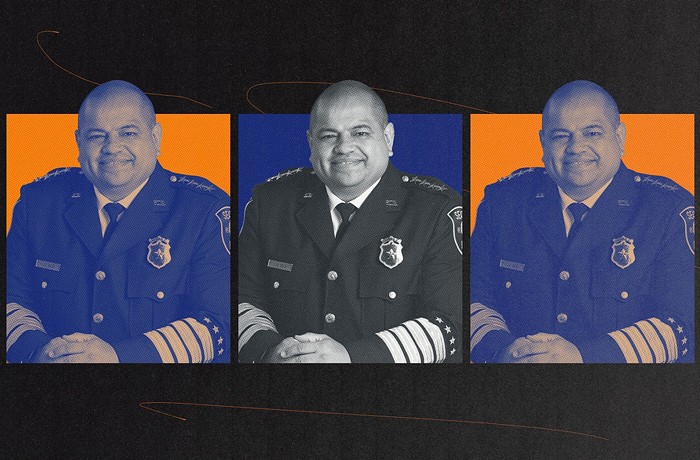

"It's been a busy three years," says SPD Gang Unit lieutenant Ron Wilson. Wilson says the gang problem—an estimated 4,600 members and counting—"outnumbers any law-enforcement resources." Wilson says gang members are now involved in just about every type of crime, including burglary, identity and auto theft, prostitution, and robbery—a major shift from the crack-focused gangs that prompted SPD to create the gang unit in the mid-1980s.

Gang detectives investigated nearly half of Seattle's 28 homicides in 2008, all young black men who died in a hail of gunfire. By now, you've likely forgotten their names. Here are a few: Allen Joplin, 17, shot to death at a high-school party on Lower Queen Anne. De'Che Morrison, 14, killed days later near his South Seattle home. Pierre LaPoint, 15, gunned down near Rainier Avenue South and Graham Street in August. And Quincy Coleman, 15, fatally shot near Garfield High School.

To keep that list from growing, Mayor Greg Nickels and the city council have trotted out the Youth Violence Prevention Initiative, a $9 million program designed to "reduce youth violence by 50 percent" and provide alternatives to the gang lifestyle, according to the mayor's office.

For all the good the program will do, there's a lot it might not. Part of the problem is in the name: Youth Violence Prevention Initiative. Prevention—cutting gang recruiters off before they can recruit middle-school kids into gangs—seems like an obvious solution, but prevention only addresses half the problem.

"Those kids in high schools have probably been around the gangs long enough that it's tougher," SPD's Wilson says. "Prevention won't work. They're already so involved." Middle-school kids aren't the ones pulling off daylight drive-bys on busy blocks or bleeding out on street corners.

And if hardened gang members are beyond the reach of prevention efforts, the city only has two other options: Count on the bigger, badder gang unit to arrest the city's way out of the problem or hope that intervention—reaching out to gang members to try to help them escape gang life—works. But that might be easier said than done.

Tom Boerman, a former cop, parole officer, and gang consultant based out of Eugene, Oregon, says that while there are working models for intervention in other cities, the wrong people are usually in charge of designing anti-gang programs. "If what you were looking at was a medical issue, the people making the decisions would be the epidemiologists," he says. "With gangs, the elected officials make the decisions and tell the law enforcement [how to deal with it]. It's kind of backwards."

According to Boerman, the gang problem isn't homogenous and members must be approached based on their individual needs. "What happens if we convince a young man to become part of an intervention program, but all the guys who used to be his rivals are still on his ass? He has no protection because he's left the gang."

Most of all, Boerman says, the city will have to overcome the hopelessness and despair found in gang-involved youth. "These gang kids will tell you, 'Fuck, man, I'm not going to live to 20 years old. There's a bullet out there with my name on it,'" Boerman says. "They feel like they're dead walking. It just hasn't happened yet."

The city has already put police resource officers into four middle schools and one high school in hopes of keeping violence out of classrooms and guiding kids away from gangs. Part of that $9 million will also go toward keeping community centers open later—hopefully giving potential gang recruits a place to go—and will pay for anger-management classes for youth and a small army of social workers to help steer young recruits and older members out of gangs. So far, the city has a list of 762 names of kids from Southeast, Southwest, and Central Seattle from court referrals.

Those resources may help keep kids from becoming gang members, but they won't help older kids who are already deeply entrenched in gang life. Which raises a question: If the city has known the gang problem has been getting worse since 2008, why did it take so long to act? "It's easy to be a Monday- morning quarterback," says city council member Tim Burgess, who worked with the mayor on the initiative. "We could've responded better. I think what we can say today is we are firing on all cylinders now, and I think our responses are good ones." ![]()