In today's Public Safety Committee hearing, Mayor Harrell's office updated the Seattle City Council on its plans to develop a team of alternative responders to handle low-level 911 calls. Though this work dates back to the protests following George Floyd's killing in 2020, so far details still remain scant.

During the Durkan administration, concerns in City Hall about a potential conflict with the rank-and-file police union stalled progress on this issue. But last week, Public Safety Chair Herbold told The Stranger that she wanted to move more quickly now regardless of those possible objections. Based on the lack of material updates from the Mayor's Office at today's hearing, however, it doesn't look like the executive branch shares that same sense of urgency.

At the hearing, the main discrepancy between the Council and the Mayor's Office centered on whether to slowly build a new non-gun-and-badge department of public safety in its entirety, or to move forward in the short term with some sort of pilot program running parallel with that development process. Councilmembers Andrew Lewis and Lisa Herbold repeatedly expressed impatience at the lack of such a pilot, which Senior Deputy Mayor Monisha Harrell met with polite nods and expressions of confidence in the "shared goals" of the Mayor's Office and the Council.

While their goals might align, the pace at which the Mayor's Office is moving to accomplish those goals didn't seem satisfactory to some members of the Council.

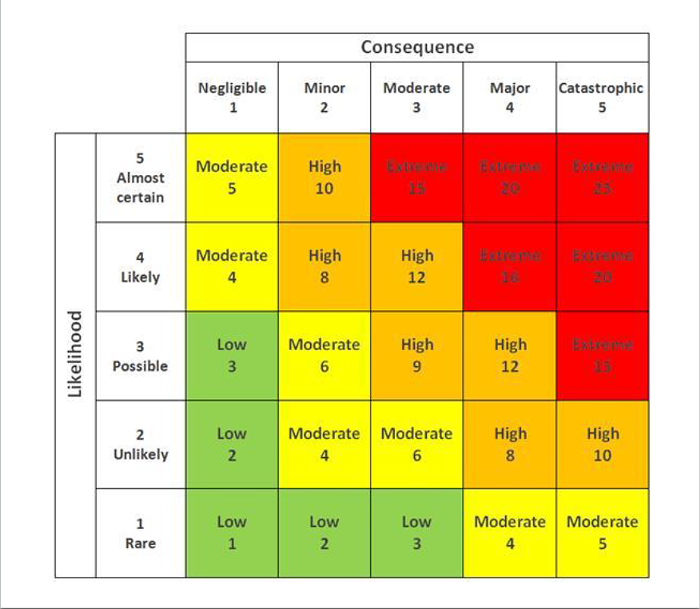

Herbold expressed frustration that Harrell didn't have the results of the Seattle Police Department's "Risk Managed Demand" analysis of 911 calls, which Harrell said she expects to receive "any day now." That analysis will classify the 911 calls SPD studied according to a matrix showing the certainty and severity of violence involved in responding to a given type of call. The report would then recommend the kind of personnel that should respond to those various classifications.

During the meeting, Herbold said the City did not need that analysis to make progress on developing alternative first-response programs. After all, she argued, 911 dispatch and SPD have been effectively triaging calls for service since 2021 due to the officer shortage.

Harrell countered that point by citing other shortages of personnel available to stand up alternatives. She noted that the existing Community Service Officer unit, where Herbold suggested finding the talent to lead a program in the short term, only has 13 people to cover the entire city.

Councilmember Lewis disagreed with that reasoning and repeatedly expressed support for a pilot program as small as a one-van team, which he said was the model used by other cities that have lapped Seattle on this issue.

Central staff for the Council chimed in to confirm that they'd conducted a cost estimate for a similar program here in town. They pegged the total budget needed at a paltry $700,000 to $1 million out of the City's $1.6 billion general fund. That bit of evidence from the Council's central staff showed cracks in the Mayor's #OneSeattle messaging on public safety: When Senior Deputy Mayor Harrell asked for a copy of the analysis, the staffer said she'd already sent it to the executive's office.

That revelation led Herbold to ask if the Mayor had invited the Council's central staff to participate in his office's interdepartmental work on police alternatives. The last update on those talks in May revealed that his office was still negotiating how and when the Council could "plug in" to that work. Central staff confirmed that those negotiations remained ongoing, and so they have not been directly involved in any policy discussions.

Lewis later chimed in to clarify that he didn't want to be perceived as blaming the entire situation on Mayor Harrell's administration. When he acknowledged that they've been more engaged on the issue than the Durkan administration, the two branches of government shared a brief moment of unity in denouncing the prior Mayor's lack of material progress in standing up Triage One, a pilot program that the Council has already funded.

But that unity proved transitory, as Lewis pressed to have his one-van pilot idea built as quickly as possible on the foundations of whatever work the Durkan administration actually accomplished. Harrell expressed doubts about the efficacy of such an idea, repeatedly falling back on the talking point of not wanting to "set anyone up to fail."

Those reservations don't seem to match the reality of the work already happening on Seattle's streets. As I reported last week, there's already an organization that's proven it can handle low-level calls for service like the welfare checks Lewis harped on during the meeting. Shifting those calls to organizations such as We Deliver Care would allow SPD to focus the limited number of police officers it has on responding to more serious emergencies and investigating violent crimes like rape.

However they decide to structure the program, supplementing the cops with some sort of an alternative should be an urgent priority. SPD Interim Chief Adrian Diaz recently blamed the need to bring down 911 response times as the reason he needed to shift officers from investigative units to patrol. If SPD only had to send officers to its most serious calls for service, the department would presumably have more personnel available to try solving crimes.

In the meantime, we’ll get even more Seattle Process™as the Council pushes the Mayor's Office to move on this issue at least at the same speed as fucking Albuquerque, that famously progressive hub of policy innovation.