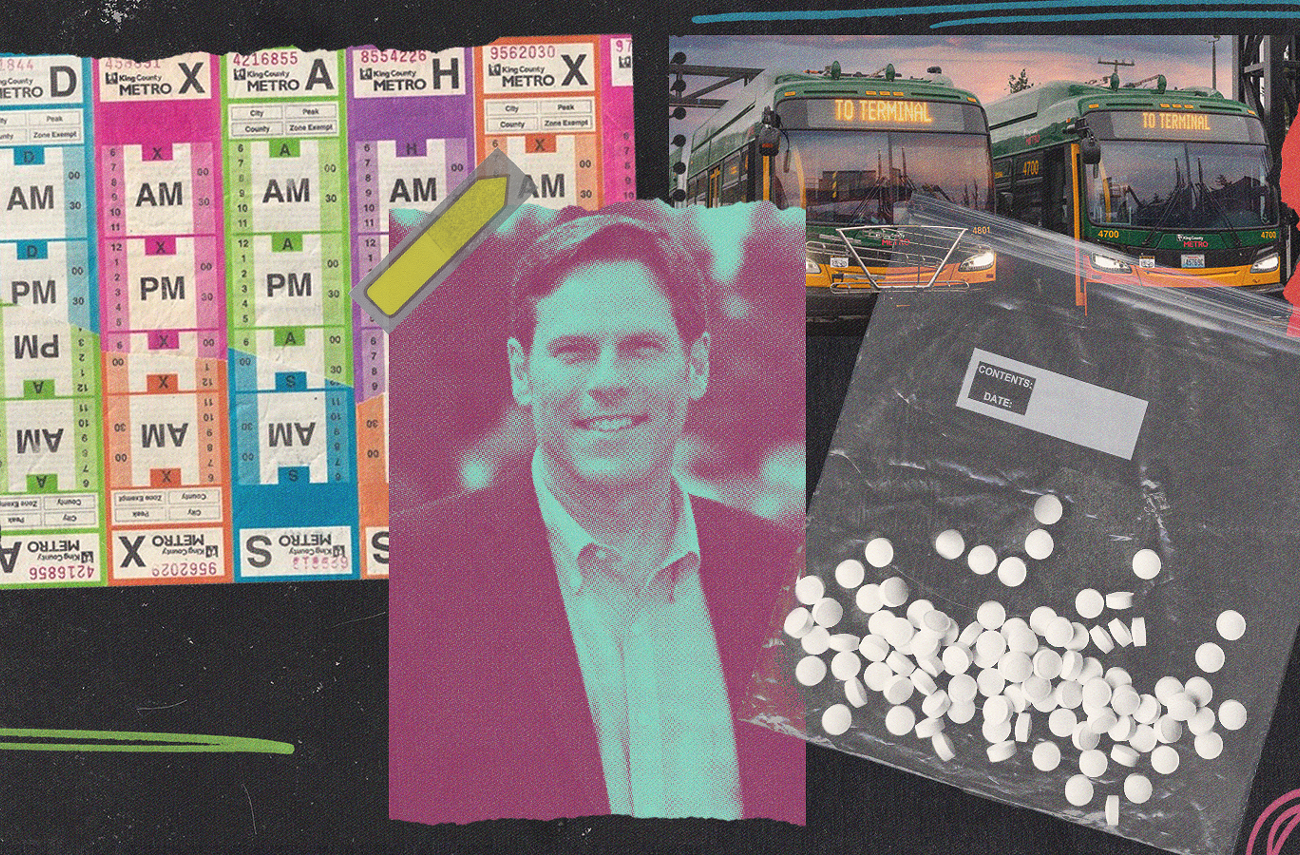

In May, Federal Way Mayor Jim Ferrell, who is also running for King County Prosecutor, signed a redundant law to prohibit smoking fentanyl in public spaces, such as in parks or on King County Metro buses. So far, the move has yielded more headlines than arrests.

According to public records, Ferrell’s cops didn’t make a single arrest for violating the new ordinance in its first three months on the books. I asked Ferrell for any additional evidence of enforcement at The Stranger’s endorsement interview last month, and then again prior to publishing this story. He has not provided any such evidence, raising questions about the connection between “tough-on-crime” rhetoric and actual results.

Ferrell’s response to the uptick in drug use on Metro buses drew criticism from the County’s leading policymaker on criminal justice reform. King County Council Member Girmay Zahilay, who chairs the Council’s Law & Justice Committee and who has endorsed Ferrell’s opponent, Leesa Manion, called the mayor’s approach “unserious.”

“Virtue-signaling might win elections, but it doesn’t solve problems,” Zahilay said in a statement.

Manion, who works as the chief of staff to current King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg, called drug use on public transit “unacceptable and dangerous” for everyone involved, but she also called out Ferrell’s proposed solution as “ineffective and unenforceable.”

Almost Comically Unenforceable

Ferrell’s law made smoking fentanyl in public places a gross misdemeanor punishable by up to a year in jail and a $5,000 fine. However, federal law already prohibits possession of fentanyl without a prescription. In council meetings, Ferrell touted the measure as a way to empower city cops to immediately intervene when people smoke fentanyl on the bus, but those cops could already do that by choosing to enforce the federal law.

Both Manion and Zahilay suggested that Ferrell simply wanted to make headlines during his campaign for prosecutor. If publicity was the goal of the policy, then it certainly did its job.

The lack of arrests over this ordinance isn’t terribly surprising once you think about how difficult it would be to enforce. Someone, either a passenger or the bus driver, would have to notice someone smoking what they believed to be fentanyl on the bus. Then that person would have to call 911 while they were still within the city limits of Federal Way, since Ferrell’s cops lose jurisdiction to enforce the ordinance once the bus crosses into the County.

If all of that happened, the cop would have to pull over the bus, take statements from everyone trying to get to work or to a doctor’s appointment or whatever, and then arrest the person accused of smoking fentanyl.

How Do We Stop Drug Use on the Bus?

As Zahilay points out, actually reducing the frequency of drug use on public transit requires a more detailed plan than simply passing a law to prohibit it.

“You can write legislation that says 'use of fentanyl on buses is a gross misdemeanor,' but who is going to enforce that law during these staffing shortages?” Zahilay asked. “[H]ow will this person with zero income pay a $5,000 fine? How is jail time going to stop rather than exacerbate this user’s addiction? And how will jail time even be likely during a time when the jails are far beyond capacity?”

Manion, by contrast, said she supports a plan from King County Executive Dow Constantine to hire additional “non-law enforcement safety officers” to address disruptive behavior on Metro’s buses. Constantine’s plan includes $21 million to hire those officers and another $5.1 million to fund a Community & Human Services Department program to connect people in crisis on Metro’s vehicles to treatment.

That approach makes practical sense, since the County has authority over its buses along their entire routes, not just within the city limits of one suburb. Prioritizing treatment for people struggling with addiction instead of reflexively locking them up will also likely reduce crime in the long term, as research shows jail has little to no effect on whether people commit more crimes.

With ballots due in two weeks, we’ll soon find out whether King County voters care more about data-driven solutions to stopping criminalized behavior, or if they’d prefer to elect politicians who pander to their basest impulses without doing anything to address the problem.