What Harrison is getting at here is the ordeal of reading. The unique and strange trial of it. The test. A turn of phrase, the piling-up narrative arabesque, convolutions, involutions, convulsions, twists of fate. There are trick questions and hieroglyphic puzzles. The solitary struggle. And only then, after slogging through, reaching the book's end, the life-altering reward, the changed mind -- and only then, just maybe.

It is not just so with Dostoyevsky -- or with Faulkner, Joyce, and Virginia Woolf. Not just the plump, stately prose of the modernists, and the narrative disinclinations of the postmodern cutters-up. Every novel, essentially, is an ordeal, and the nature of this ordeal is both proposed and actual. Fancy and fact. Which is to say, entirely existential.

The novel transmits something, in language, from one head to another. This invisible transmission is balanced ever so delicately on a fulcrum of forced understanding, of bringing what's dead and undead and foreign and familiar to synaptic, imaginative life. Reading is always, every time, an act of resuscitation: The reader exhales into the pages, the pages breathe back. If it can be granted, then, that existence itself is an ordeal, what every novel proposes to do is an illusion. An illusion predicated on an illusion -- the recombined illusion of existence's ordeal. This holds as true for Valley of the Dolls as it does for Ulysses.

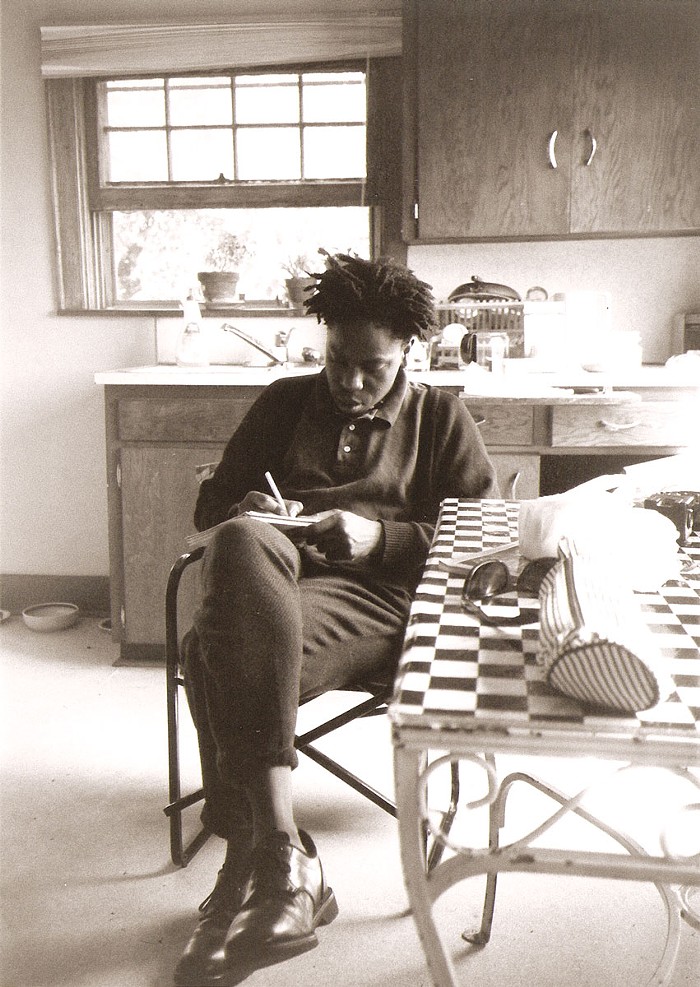

Then there's the actual ordeal of the novel, the crisis of its mechanics, which is inherent, insurmountable. The book of fiction, whether a piece of trash or a world treasure, seeks to resolve itself in an act of communication that can never truly be verified. That's literature: one-way conversation without eye contact -- though the eye is very busy. The connection is frantic, artificial, and unrequited. This statement, I know, is a bit fancy. It smacks of a pretty highfalutin smirk of futility -- but, in a most fundamental sense, there is an undeniable aura of futility surrounding the novel, something that gets at the deeply solitary nature of both its creation and its reception. Uncle Remus doesn't orate anymore; he writes in Hemingway's sparse little room. Alone. Unsupervised. Unwatched. Every new novel written (written, that is, as a novel qua novel, and not a transcribed TV drama) is just one more lovely jigsaw piece of muted, mutated desire seeking impossible reconnection to the daydream of communion.

Yes, after all is said and done, novels tell stories, too. Of course they do. Everyone tells stories -- to themselves, to each other, lovers, friends, landlords, priests, cops. But, since we're trying to get at something else, something kind of difficult, let's keep with this fancy idea of the novel as a barely viable form of art, as an artifact that is at once a symptom of and a cure for the unavoidable solitude that comes from existing in a world that is too big, too new, too anonymous, and therefore, sadly enough, too private.

That the too big, too new, too anonymous, and too private nature of our speedy world didn't always pertain is exactly why the novel struggles on, in severe default, as an arid form of civic communication. Novels are a strung-out crab-walk around loops of amphetamine time; forward and back, novelists scamper for the listener fix. So, where's the audience? Who's listening? Who cares?

Because the basic formula and structure of the novel descends, obviously, from the bygone tradition of oral storytelling, writers of novels are, on some retroactive level, approximating the conditions and features of group communication. Not too very long ago, that good old tradition was metastasized, through diaspora and alienation and a million other highbrow and lowbrow factors, into dictation, and then self-dictation. In the mind's infinitely receding house of mirrors, fiction writers search for the discernible ear, the familiar but discriminating listening of the tribe, which will also be the speaking of the tribe. Yet they can never, ever find the proper audience. The proper audience doesn't exist: They can't get there from here, and there ain't no going back, either. The audience is everyone and no one -- and, the writer. Anonymity is the sounding board confronting writers as they confront the lonely, white blankness. So novelists just blather on and on and on, transcribing themselves to the singular universe, and hoping someone, anyone, understands.

Understanding is hard to come by, if not impossible. Those sad sacks who scribble out fiction are inherently cursed to reiterate and rephrase themselves like nit-picky lunatics yammering away in a vacuum of inattention. No matter what the ostensible subject of literature, its true subject is continuous self-reflection and self-absorption transformed to public portraiture. The medium of the portrait is language, and the portraiture itself is story. Every time another author taps out "the end," every time another book goes to press, hits the book store shelf, ends up in your -- dear reader -- hands, a brand-new dialect is added to the polyglot universe. Or something like that. And given that something like that might just be the case, then it follows that within any given single language, there are an infinite number of languages -- infinite dialects spilling out from literature's limitless Tower of Babel. Which is always under construction.

In other words, every novelist is always saying, "In other words." Once in a while, the reading of these other words -- which spool out like a ticker tape in stop-time from the writer's exiled imagination -- appears impossibly difficult. Impenetrable. Obtuse. Way too cute, or clever, or Joycean, or Proustian, or Kafkaesque. What do we really mean when we say a particular book is difficult? Or too difficult? Reading, like the acquisition of language itself, demands an intense engagement of these crucial things: long spans of time, huge reservoirs of patience, the hard work of remembering, and an immaculate attention to detail. When any of these faculties are immoderately taxed by a certain writer's ambitious or overactive or rococo ticker tape readout, a book is deemed difficult. When all four are pushed to the extreme limit, we have something like this: "There would be the dim coffin-smelling gloom sweet and oversweet with the twice-bloomed wisteria against the outer wall by the savage quiet September sun impacted distilled and hyperdistilled, into which came now and then the loud cloudy flutter of the sparrows like a flat limber stick whipped by an idle boy, and the rank smell of female old flesh long embattled in virginity while the wan haggard face watched him above the faint triangle of lace at wrists and throat from the too tall chair in which she resembled a crucified child...."

"I don't know anything about style," Faulkner once told a bunch of college kids. Yet, it is only by investing yourself in the intricate way he tells the story that you will get the story. And vice versa. Almost anyone -- given (or allowing themselves) time, patience, hard work, and focus -- is granted the opportunity to learn a new language here, which is the stuff of perspective, possibilities, openings, layers upon layers of meaning. Beauty.

This requires a big bad hunger, an ambition to get inside a stranger's head, to see what it sees and think what it thinks, and it is why so-called difficult literature is predominantly the domain of the young. The young are hungry. They have lots of time. The anonymous ordeal of youth seeks the anonymous ordeal of books that permanently change the nature of one's mind. Saying a particular book is difficult is analogous to -- or perhaps the very equivalent of -- looking at someone and saying, "I wouldn't want to be in that guy's head." Really reckless or really curious or really bored people actually want to get inside other people's heads, just to see what makes them tick.

I realize I've called the novel about 14 different things at this point, but it is also this: the ticking insides of certain folks' heads, whether slowed down, sped up, folded, knotted, or generally fucked with. It's improbable that the noise inside your head, as you walk to the store, is any less convoluted or strange or rambling or fascinating than what went on in William Faulkner's. It's just familiar. And if you listened very, very carefully to that noise, and then took the long, long time it takes to get it down on paper, in a shape that suited you, which seemed honest to you, and correct, then you might have yourself a novel. Maybe even one of the so-called difficult ones -- depending on the type and volume of your noise, or the level of your ambition, or the severity of your struggle. Then I could look at your book and ask myself this: Do I want to make this unfamiliar thing familiar? Can I make it communicate to me? Do I have the time and patience?

To call the book difficult, at this point, would just be tautological.