The infamous "No Protest Zone" was established by then-Mayor Paul Schell and then-Police Chief Norm Stamper on December 1, 1999, after a turbulent day of protests (busted Starbucks windows, tear gas) had overtaxed the city's police force. The order mapped out a 25-block area between Lenora and Seneca Streets and Third Avenue to Boren Avenue that excluded anyone other than WTO conference-goers, residents of the zone, press, city officials, public safety workers, and owners, employees, and patrons of area businesses. (Chief Stamper explained, "You couldn't shut down the core of downtown during the Christmas season.")

More to the point: No protesters allowed! And, like doormen at swanky Manhattan nightclubs, the police officers on the scene got to decide who met the admittance prerequisites. (I, for one, was turned away despite my official WTO press pass.)

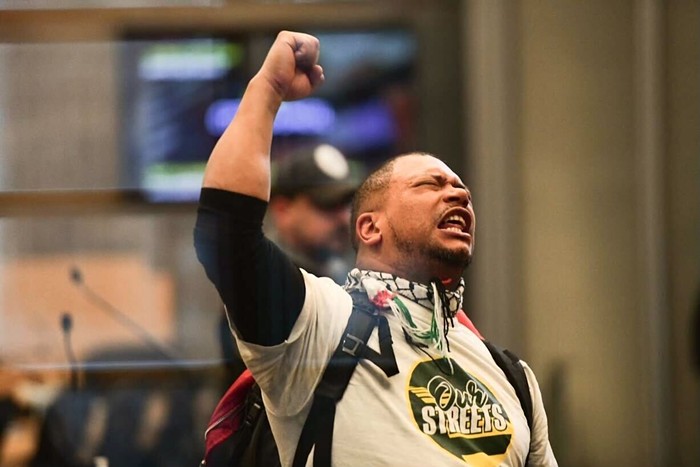

More important, others who ran into trouble with the police were Victor Menotti, Thomas Sellman, Todd Stedl, and Doug Skove--the ACLU's plaintiffs. All four were either arrested, threatened with arrest, or searched (and had their property confiscated)--for things like carrying signs or talking about the WTO within the "No Protest Zone." Sellman, for example, spent two nights in jail for distributing leaflets.

The city writes off the ACLU's complaints as childish "First Amendment platitudes": "Plaintiffs essentially assert that their right to protest however they desired trumped other citizens' right to safe passage of emergency, vehicular, and pedestrian traffic, delegates' rights to meet, and business owners' and employees' right to earn a living," the city's brief states. U.S. District Court Judge Barbara Rothstein agreed with the city in 2002, after a two-year court battle.

ACLU staff attorney Aaron Caplan, who wrote the appeal for the February 6 hearing, says the ACLU recognizes the city has the right to protect the public from unruly protest. But, he ads, there are already acceptable mechanisms to deal with unlawful protest. (Handing out leaflets doesn't exactly fit the city's characterization of bratty demonstrators who want to "protest however they desired," by the way.)

Constitutional rights shouldn't be shortchanged because the police were ill-prepared, Caplan says. "It's no fun to be in a position where you don't have enough manpower," he says of the SPD, "but that doesn't mean you can just enact an unconstitutional law that nobody could protest in a huge area of downtown."

If that law, which, for example, prevented plaintiff Stedl from handing out photocopies of the First Amendment, is upheld, it would set a scary precedent.

The ACLU brief asks, "Did the conferral of unfettered police discretion to decide which persons had 'legitimate business' inside the zone render the No Protest Zone policy unconstitutional, by affording police the power to discriminate on the basis of content or viewpoint?"

It's a good question. Hopefully the lasting effect of Seattle's WTO protests won't be a precedent-setting law that answers in the negative. The case could be headed to the U.S. Supreme Court.