What happens when a composer dies? Obituaries, encomiums, and perhaps a scholarship award or a book might appear, but what about the music? In 2001, composer Barton McLean aimed a provocative article at his peers, "What Might Happen to Your Music After You Die (and What You Can Do About It)." McLean wisely points out that the fate of a composer's life work can be unpredictable, sometimes perilously so. Fame offers no assurance of preservation, but it helps. Previously lost or unknown pieces by Moz1`art, Hector Berlioz, and Anton Webern have turned up in recent years. A gold medal awaits whoever finds Stravinsky's lost 1940s symphony or the 1908 Chant Funèbre.

Three recent releases highlight the possible fates of a composer's oeuvre. No one would mistake Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959) for a major 20th century figure; however, his Bachianas Brasileiras magnificently graft brainy, Baroque-inspired counterpoint (the "Bach" part of the title) to the folk tunes and rhythms of his native Brazil. Although other recordings remain available, Bachianas Brasileiras (Naxos) is a welcome, budget-priced luxury, grouping these nine pieces, scored mainly for orchestra as well as soprano and cello ensemble, into a convenient, well-recorded three-disc set.

By contrast, Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001) ranks among the titans of the 20th century. Xenakis pioneered granular synthesis, interactive musical games, computer-generated music, and the translation of higher mathematics (Markov chains, Brownian Motion, sieves, etc.) into music, however new recordings appear infrequently. Performers get deterred, if not intimidated, by the technical demands of his scores and may fear the audible result: an overwhelmingly loud, ferocious sound world. Xenakis: Music for Strings (Mode) collects six captivating pieces for string ensembles of various sizes, from the brief, valedictory Voile for 20 strings (1995) to the lumbering, tour de force for solo double bass, Theraps (1975–76), to the seminal 1959 electronic work Analogique A+B, which betters the version on Iannissimo! (Vandenburg). Essential.

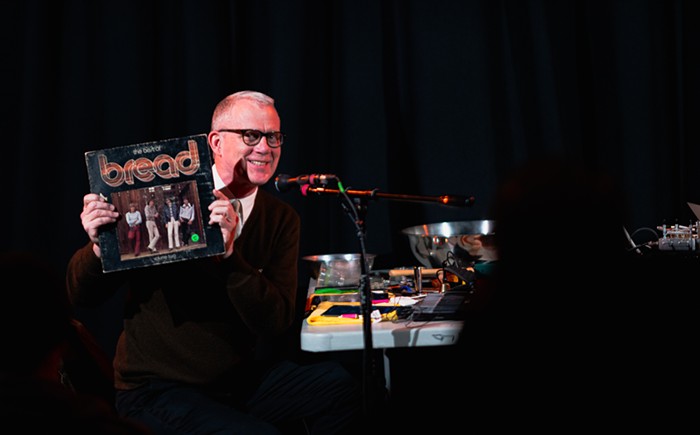

Some composers almost disappear altogether. As a kid, I adored and imitated Julius Eastman (1940–1990) for his unforgettably maniacal singing on the old Nonesuch LP of Eight Songs for a Mad King by Peter Maxwell Davies. Alas, I had no idea he was a composer who died in pitiful obscurity. Unjust Malaise (New World) rescues a composer who was gay, black, and outspoken enough ("There are 99 names of Allah, and there are 52 niggers...") to compose an evening-length trilogy for three pianos, Gay Guerrilla, Evil Nigger, and Crazy Nigger. Eastman was a minimalist with a light touch; his music bobs, pulses, flows, and rushes. The buoyantly infectious Stay on It (1973) foreshadows the frisky pop-inflected 1980s work of Michael Torke while "Prelude to the Holy Presence of Joan D'Arc" (1981) is a spectacular solo setting for Eastman's regal, stentorian voice.

I also enjoy the compilation Voices in the Wilderness: Dissenting Soundscapes and Songs of G.W.'s America (Pax). It's wildly uneven, though I gotta love pieces like "America, Fuck Your Freedom" by the United Satanic Apache Front.