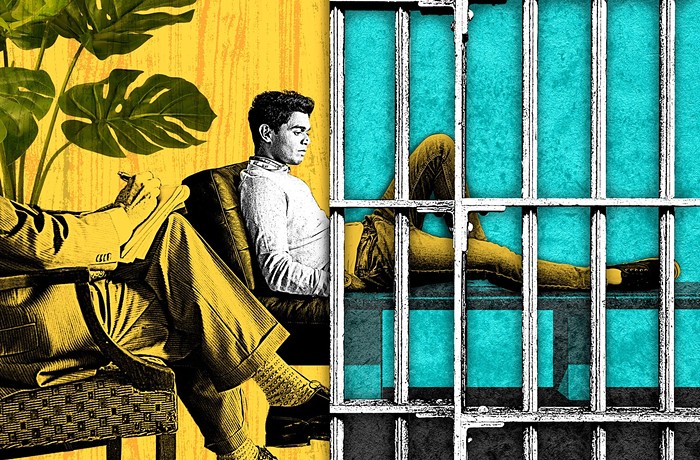

Like every labor management dispute, this one is all about money. The folks currently marching the picket line are manifestly disgusted by the corporate greed of Boeing's upper-crust officers. All that the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace (SPEEA) wants for its membership is a comparatively bigger slice of the pie. And management has told them to lump it. The workers are angry. The executives are stubborn. In this regard, the strike has all the hallmarks of a traditional labor dispute. But this time, there's a crucial difference: The people sporting class-war slogans on the picket line aren't rivet-heads. With their college degrees and intellectual free-agency, the striking workers reside in a financial and professional zone located somewhere between management and the machinists. Engineers and technical workers at Boeing earn an average annual salary of $55,000 and $45,000, respectively. Quite possibly, the comment most dreaded by the people on the picket line is this: It's really hard to feel sorry for someone making that much money.

The picketers are fully aware that their "white-collar" status creates a P.R. dilemma when it comes to drumming up public sympathy and support. Jerry Robinson, a picket captain, says, "It's hard for people to understand why a Boeing technical worker would go on strike," he says. Robinson then goes on to point out that SPEEA isn't "asking for the moon."

On paper, SPEEA's demands appear legitimate. Usually, engineers and technical workers can expect around the same annual pay increase as that given to members of the International Association of Machinists & Aerospace Workers, whose contract is negotiated three months prior to SPEEA's. When this comparative increase failed to materialize during contract negotiations in early December of this year, the shit hit the fan. This was only the final insult in a list of corporate abuses, which include discretionary individual (as opposed to collective) pay raises that are not pegged to inflation, a lack of bonuses, and negligence in providing long-term disability insurance. According to those now on the picket line, this strike was inevitable.

Robinson points to the strikers' desire to hammer out some long-term job security in the changing marketplace. Here, he speaks in terms of generations, rather than days and weeks. "We're creating a future for our children," he says. "We're in a power struggle."

But the traditional class-war rhetoric doesn't quite fit bespectacled and gleeful Robinson.

"This is a new experience for us," he says. "Many people have realized the value of a union." Surprisingly, the re-educated Robinson does not break out into a chorus of "The Internationale" at this point.

Certainly, Robinson and his colleagues are legitimately angry; however, this new working class consciousness is tinged with a certain luxury.

In the long run, it might be the strikers' own economic status that proves the greatest hindrance to union solidarity. Unlike, say, the machinists, or even the teamsters from whom they've received a show of public support, the workers represented by SPEEA garner a higher mobility on the job market: They can up and leave. With their technical skills, they have options unavailable to those on production lines. And ironically enough, one of the "success stories" in an SPEEA flyer relates that some engineers at Boeing "cleaned out their work area before they left, and plan to look for new (permanent) jobs during this strike."

In professional sports, this is known as the prerogative of free agency, which many fans feel to be a detriment to team play. This kind of ship-jumping by disgruntled Boeing employees could ultimately do damage to the general cause of the strike. It could also come back to bite them right in the ass, because the same thing that allows them to leave a particular employer makes them disposable on the free market. Many of the striking engineers and tech workers feel that it is just this professional mobility that provides them with a much-needed ace-in-the-sleeve in negotiations. However, their ability to move elsewhere destabilizes the union. As Tony Parkington, a picketing Boeing engineer, puts it, "The most employable people are the ones who are going to leave first." This overt threat to Boeing is obvious; what might not be so obvious is the threat it poses to the organization and bargaining power of the labor movement.