Through March 2.

Contemporary Northwest Women Photographers

Through Feb 23. (Also at the Washington State Convention & Trade Center, through March 27.)

Frye Art Museum, 622-9250.

The Female Aim

G. Gibson Gallery, 587-4033.

Through Feb 28.

There is plenty of very good work in these contemporaneous exhibitions of women photographers, but as a qualitative judgment, this seems somehow beside the point. As collections of photographic work by women they beg a certain question, specifically the assumption that women see things a certain way (what was boringly called, for a time, the female gaze). It assumes that a show based on the female perspective will add up to something that we otherwise wouldn't gather.

Maybe as a theme this was once true. Likely it was once true. But if it's still true, I don't see any evidence of it. These days, few people will dispute that a woman's take on things can be pretty much anything at all. Which is a lovely thing for women, but it's not much to chew on intellectually, since it means the show doesn't add up to anything except, as the museum suggests, a celebration of women. And while it may very well be true that this suite of exhibitions is not meant as an argument, it's hard to banish the argument from your mind--your cognitive apparatus, after all, wants to make connections between things.

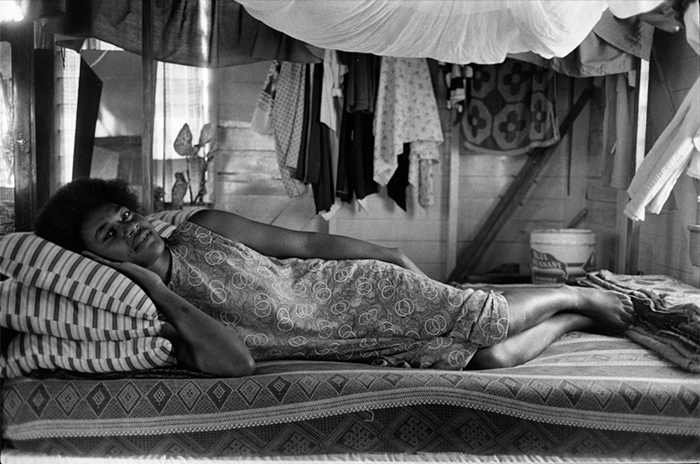

The collection of works in the Frye's Contemporary Northwest Women Photographers (there's another set at the Washington State Convention & Trade Center that I haven't seen) is various to the point of frustration, even as the work is very good: Anne Lawrence's confounding corporate landscape, with a touch of Escher; Susan Seubert's dark, dreamy, threatening waters; Ellen Garvens' photos of hands mounted on a sculpture built of surgical and hand tools (one of very few works that deals sculpturally with photography). There are plenty of images that might be called more traditionally womanly, if you are inclined in that direction--wet children in pools, disembodied hands offering an egg, a stylish hand holding a cigarette--but you only want a few minutes with a survey of the history of photography to recall Edward Weston, James VanDerZee, even Steichen's hippieish compilation, The Family of Man (and Diane Arbus, Helen Levitt, Sally Mann--all of them at the G. Gibson show) to find that as a medium, photography has always been an even-handed master.

All sorts of gender issues have grown up alongside photography--various allegations of passivity (the model, the nonintervening photographer) and unnatural aggression (the phallic, all-devouring nature of the lens). Photography hasn't been around long enough to become a firmly entrenched male art, as painting was; it was, significantly, Sherrie Levine's landmark deadpan appropriations (of, among other things, Walker Evans' photographs) that broke the concept of male authority into tiny little pieces.

As an organizing principle, then, I find the concept of "celebrating women" too loose for my taste--the use of identity politics to tell us that identity politics are no longer useful. I was more interested, as a whole, in the Frye's Pioneer Women Photographers, which features images by four women--Ella E. McBride, Myra Albert Wiggins, Imogen Cunningham, and Adelaide Hanscom Leeson--working at the turn of the last century, all of whom had some connection to Seattle. Again, it's a conceptual affiliation that doesn't quite work, in this case because of a too-light curatorial hand.

One longs for more context, to know in what ways these four were exceptional, or influenced each other--the word "pioneering," in the end, tells us very little (except in the case of Leeson, who used composite printing, etching, and manipulation to turn her photographs into seductive illustrations for a 1905 edition of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam).

But in an interesting moment, a print by Wiggins of two women languidly looking at a sheaf of negatives turns out to be an Eastman-Kodak advertisement from around 1900--which means that Wiggins was not confined to amusing herself with photos of her studio and her fellow artists, but was out working in the world. And that advertising and art began their stranglehold on each other much earlier than we'd like to believe, back in the unsullied, innocent days of the medium's beginning.