You can find O'Leary's pieces in Trouble Comes in Threes, a show at Magnuson Park Gallery that features work from three generations of artists: Elizabeth Sandvig, Erin Shafkind, and O'Leary. All work within the medium of clay, though each artist has markedly different interests. Shafkind's work revolves around shit and food, creating playful boxes with gold-covered turds perched on the lid and vases that balance veggies and hamburgers on top. Sandvig is much more interested in cats of all kinds. But O'Leary's pieces are each incredibly remarkable and distinct in their own way, unlike anything I've seen before. Especially made out of clay.

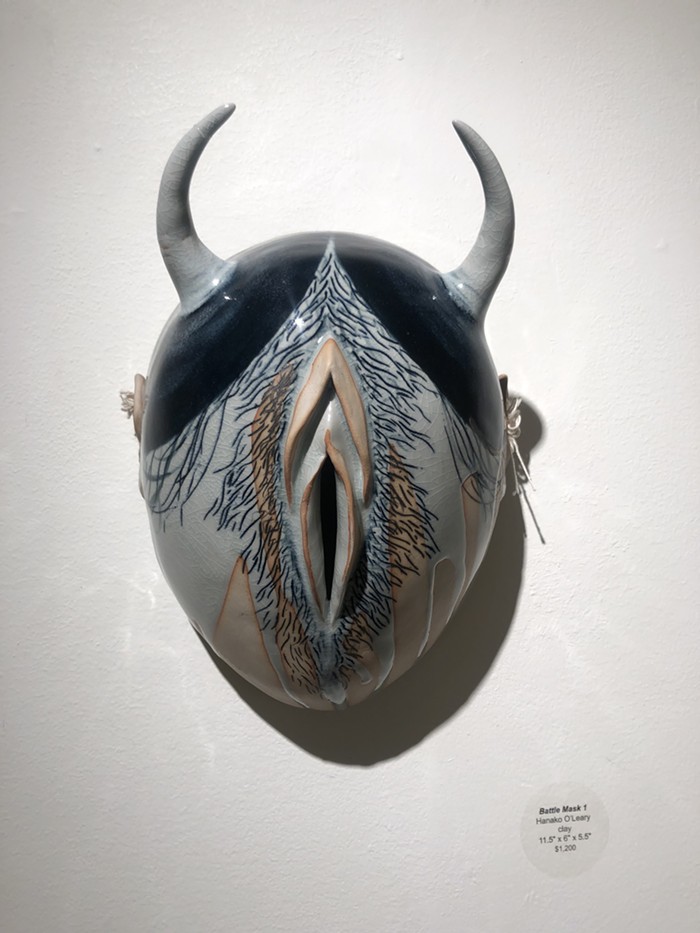

The masks pictured above are battle masks inspired by the Japanese Hannya mask and are part of a series of 12. The masks are traditionally used in Noh theater and are meant to portray the souls of women who become demons due to obsession or jealousy, their faces growing two sharp horns, metallic eyes, and an upturned mouth revealing long sharp teeth. O'Leary flips this a bit, putting a delicate and carefully sculpted vulva where the face should be, telling me it's a comparison between the two. "I believe both to be complicated, feared, deeply misunderstood, and powerful." Looking at it up on the wall, illuminated by just a single lamp, there is something compelling about it. A vulva where a face should be. Pubic hairs and all.

The other notable and impressive O'Leary piece in the show is her Utsuro-bune (Hollow Ship) in the center of the gallery. The vessel, which she refers to as a Venus Jar, is also part of a series of 12. It has no less than 20 arms rising from it—some with their middle fingers held defiantly in the air, others artfully touching the middle and ring fingers to the thumb. In the middle is another vulva.

O'Leary was inspired by a Japanese folktale from the 19th century about a strange hollow ship that washed ashore in a rural fishing village and contained a woman who could not communicate in Japanese. She had a box that she refused to open. Suspicious of the woman's motives, the villagers sent her back off to sea.

"Traditional interpretations of this story conclude that the heroine is doomed to perish at sea," O'Leary wrote me. "I understand it to mean they stood their ground and maintained their autonomy. This sculpture is a representation of the castaway and their seafaring vessel." This vessel is seriously so large and intricate, I can't imagine how big the kiln must be or how painstaking it must have been to assemble. Some of the fingers on the ship appear to have been broken off and glued back on, though it doesn't take away from how impressive the piece is. O'Leary's work really grabs your attention and reinterprets myth and tradition in a way that grounds it in the now without losing the essential tether to the past.

Trouble Comes in Threes is up until March 15. There will be a closing reception from 5 to 8pm, at which the artists will be giving a short talk on their new works. Be sure to see it before it closes!