Rioting has been an American pastime since before America existed, and it’s heartening to see patriotic Seattlites participating in a tradition that dates back to before the country’s founding. In this new series, we’ll celebrate some of history’s greatest riots, drawing inspiration from the visionaries who laid the foundation for the more perfect union we hope to one day enjoy.

Let’s begin with The Stamp Act Riots of 1765, which are often cited as the first rebellion against taxation without representation. But there’s more to the story than just discontent with the British, and a hero whose name you don’t often hear mentioned. You’re familiar with Ebenezer Mackintosh and the Boston Pope fights, right?

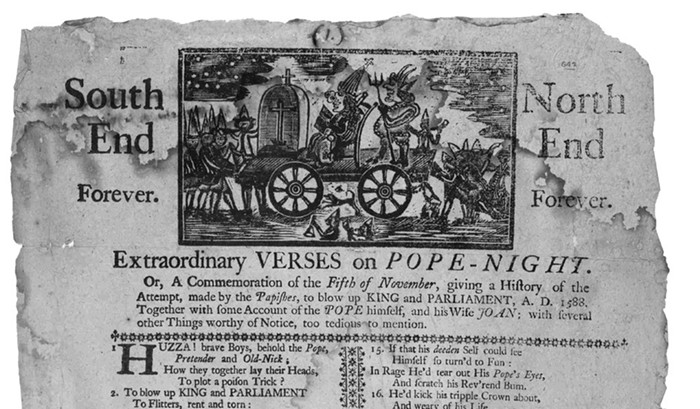

Cast your mind back to Boston of the 1760s, when gangs from the North End would gather every year to fight gangs from the South End on November 5. Pope’s Day, as the holiday was known, was sort of an American Guy Fawkes Day in which revelers would carry effigies of the Pope to a bonfire to be set ablaze, and participants tended to be “rude and intoxicated Rabble, the very Dregs of the People, black and white."

Originating in the 1600s and growing in popularity over the intervening century, the celebrations were often riotous, out of control, and sometimes deadly. In Boston, rival gangs developed an annual competition in which they would fight each other for control of the effigy, with the winner getting the honor of setting it on fire.

Authorities, as you can imagine, weren’t thrilled about this situation, and after a death one year soldiers were summoned to stop them. They were able to quell the activities in the North End, but under the leadership of a local 27-year-old shoemaker named Ebeneezer Mackintosh, the South End beat back security forces and gave the North End cover to resume their party.

Okay, so an annual anti-Catholic riot that sometimes kills people isn’t a great look for a fledgling country. But better things lay ahead: Wealthy business owners sensed that Mackintosh had the trust of common folk, and used him to lead future rebellions.

When England announced the Stamp Act—basically, the first tax on trade within the colonies, rather than on imports and exports—middle-class merchants were ready for revolt. Forming a group called “The Loyall Nine,” they arranged for Mackintosh to lead a riot against Andrew Oliver, whom the British had assigned to administer the tax.

On August 14, Mackintosh led Bostonians in revolt, bringing them to a tree where an effigy of Oliver had been hung. They cut the effigy down and led it on a funeral procession, then destroyed Oliver’s office, brought the effigy to Oliver’s home to behead it, and stoned government officials who tried to stop them. Oliver resigned the next day.

From there, the wealthy Loyall Nine and the Sons of Liberty took a larger role in leading the rebellion, and Mackintosh was increasingly sidelined.

As so often happens, it was poor and working class people who did the dirty work, with rewards reaped by wealthy men who were upset that other wealthy men weren’t letting them get wealthier fast enough.