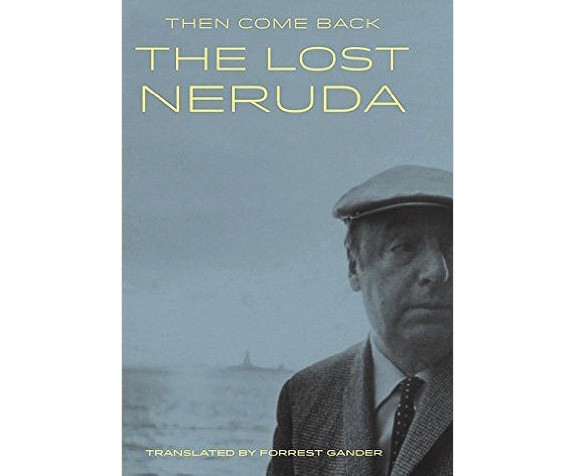

The news that Pablo Neruda Foundation archivists had found 21 previously unpublished poems by the inimitable and amorous Chilean poet did to the hearts of many readers what spring does to the cherry trees.

The worry in such situations, though, is that the poems will be bad.

A cynic considers the market. Pablo Neruda—who, according to newish reports from the Chilean government, may have been assassinated (he died less than three weeks after General Augusto Pinochet's 1973 coup)—is one of five poets most Americans can name. The foundation probably found a bunch of scraps crumpled in the back of some rolltop desk in storage—they would hardly not publish them. Even Forrest Gander, the great professor/poet/novelist/Pulitzer Prize finalist who renders the lost poems into English, admits in the introduction to having said that "the last thing we need is another Neruda translation," and he worries that a lost-poems-found edition might just be a case of "squeezing the last purple juices from the Neruda estate."

On Tuesday, April 19 at McCaw Hall, Copper Canyon Press will give these poems their full English-language debut.

Moreover, for me, Neruda is one of those poets who have always required a certain amount of forgiveness in the first place. As with his US analogues Walt Whitman and Frank O'Hara, if you're not in the mood to lust for life, then you might find Neruda's poems kinda tedious, a little drippy, larded up with bread and wine and adjectives. "I GET IT," you might say.

Even the ordinary spoon is extraordinary. Her eyes usurp the sun and yet are deeper than autumn's mysteries. Fascism is death, etc. But if you're a beer into a free afternoon and you don't have much to do the next day and you're entertaining a mild flirtation with some wonderful person for the first time in a long time and you realize that not even you can stand to live your entire life in a cloud of semi-meaningless work and self-sustaining irony, then it's much easier to roll with Neruda's more-than-occasional gush.

Luckily for us all, cynicism and skepticism prove to have been the wrong models for considering Then Come Back: The Lost Neruda. The majority of the apparently complete works included in the book are as good as Neruda poems can be, and exactly five are true shining gifts to the world. That's saying something. Having five of 21 poems be good is about the same as liking three songs on an album: a rare accomplishment.

Additionally, and to the cultural materialist's delight, many of these poems were scribbled out (in green pen, which I find affecting for some strange reason) on scrap paper, napkins, playbills, and other ephemera. Ogling the full-color scans of the original material reproduced in the book feels as if you're discovering the poems along with the archivists. (My favorite one is a love poem that uses a lot of food metaphors that was written on a piece of stationery that says "Menu.")

Covering a little over 20 years of his life, the book works like a Neruda sampler, revealing sides of the poet I hadn't seen before. We get a few odes (for which he was known), powerful political poems, melancholy poems of exile, and, of course, a gob of love poems. The poems are also formally various—some discursive and free-versey, some impressionistic, some driven by anaphora and other older forms.

My favorite new Nerudas are the Cranky Neruda Who Hates the Telephone and the Hopeful Neruda Who's Into Outer Space. "The astronauts / didn't go by themselves..." he writes in Poem 21, "something floated up like / a wedding dress / behind the two spaceships: / it was our spring earth / blooming for the first time / that conquered an intimate heaven." I wouldn't expect a poet of mud and "legs bequeathed the creaminess of perfect / oats" and anticolonial sentiment to entertain a romantic view on the colonization of space—and, indeed, Lizzie Davis, another translator who worked with Gander on the book, mentions in a note that Neruda has been critical of space travel in the book—but there it is.

While we're in the heavens, I'm glad Neruda risked this metaphysical take on the moon: "It grew swollen cruising the air unhurried, unmarked / and we didn't imagine that you and I made up one element of its motion, / that it's not merely hair, languages, arteries, ears that compose the shadow of a man / but also a thread, a fiber stronger than nothing and no one, our time coming and running down and swelling to fit this attenuated hour."

The idea that humans are made of star stuff is common, but the idea that we inherited from the big bang something seemingly immaterial—gravitational relation, celestial motion, spin—feels novel. This lost and found work unearths a philosopher-poet in Neruda, one who kisses the skull behind the lips but who isn't going to let a little memento mori overshadow the transcendent capacity of human love. ![]()