The first time I saw him was on a giant screen at a bathhouse in the summer of 1984. Sitting on a carpeted banquette, with only a white towel wrapped around me, I watched him climb a tree to rescue a skydiver tangled in a parachute. He and the skydiver had sex in the tree, of course. The room was filled with men transfixed by the screen. Their faces, illuminated by the flickering light, looked up in awe, as if they were watching a mother ship land.

"Who is that?" I asked the guy sitting near me.

"That's Al Parker," he whispered. "He's a fucking legend."

Everyone's focus was on the tan, ripped, bearded man on the screen. With his dark piercing eyes and chiseled features, he emanated an unapologetic, raw sexual charisma that I hadn't seen modeled before, not among men, not in movies or television, and certainly not in Utah, where I'd grown up. The spell in the room broke when the credits rolled. The other guys in towels returned to wandering the bathhouse.

"I'd love to paint him," I remember thinking.

It wasn't hard to find Al Parker videos. In many stores, he had his own section. I studied him, his expressions, the way he moved, the way he made sucking cock a religious experience. Maybe I thought that because he reminded me of Jesus. I wanted to be like him. I stopped bleaching my hair and got a shorter cut. I tried growing a beard, but it made me look Amish.

At this time, almost everyone in the public eye—celebrities, politicians—were still in the closet. Gay culture had just entered the nightmare of the AIDS crisis. Living in Los Angeles, I worked at the Pleasure Chest, a store that sold biker jackets, leather chaps, boots, hankies (which came with a pocket-size foldout hanky code), paddles, tit clamps, magazines, and videos. It was a different world back then. Hanky codes and most porn magazines have faded out of existence, along with the stores that sold them.

One day, I was holding a 20-inch double dildo over my shoulder when I saw someone's reflection in the glass case. "Can I help you?" I asked.

I raised my head, and it was him, Al Parker. "Poppers and one of those cock rings," he said. His close-cropped beard revealed naturally rosy cheeks, and his tight jeans accentuated his crotch.

"Size?" I stammered.

"Large," he said.

"Of course! I mean, coming right up," I said, sounding like I was serving cheeseburgers.

Or maybe that's how I remember it because later, after moving to San Francisco, I got to gaze into his dark, soulful eyes again while waiting tables at a diner.

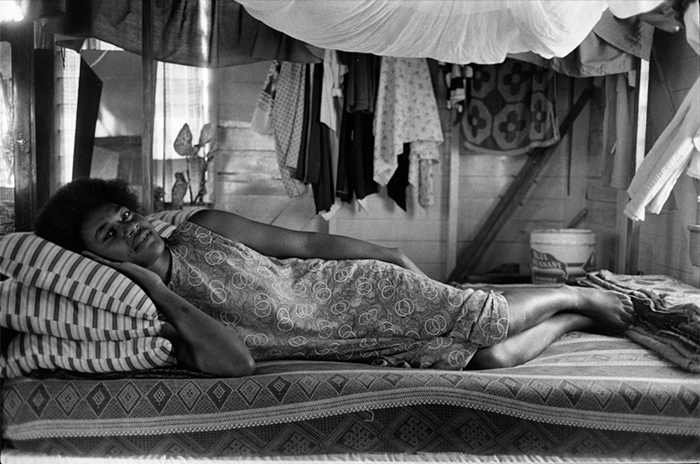

Orphan Andy's was a classic greasy diner with two window tables, a row of booths, and a long counter. The Tiffany lamps looked plastic, and the fake potted plants looked thirsty. The jukebox played everything from Edith Piaf to the B-52s. Orphan Andy's existed outside of time—or in all eras at once. It filled up after the bars closed, sometimes with a line out the door. I worked the quiet afternoon shift. Regulars told me stories about the glory days—before the acronyms and dark diagnoses. Every Thursday, the gay paper was filled with pages of the faces of newly dead men. Ruby, a retired security guard, abruptly announced one Thursday, "I don't want to hear about it. I don't want to know anymore—who died," and slammed her paper down.

"I refuse to go to another goddamn funeral," said Gary, a 76-year-old leatherman. "Just throw me over a fucking bridge."

"Right now?" said Ruby.

"My ashes, you asshole!" Gary said.

Ruby cackled. "After you die, old man, I'm not going to make any new friends. I refuse to watch another person wither."

Grief hung over the city like smog. I hadn't lost anyone close, but I grieved for how life had been—the smiles I used to get from men on the street, the lingering eye contact, the exchange of glances to the crotch. It was okay if it didn't lead to a hookup, there had at least been a connection, a mutual sense of "I see you," a measure of validation. As men were dying, I'd come to feel invisible, like an out-of-focus extra on the set of someone else's nightmare.

When the diner was slow, I'd watch the endless parade of strange and beautiful passersby. Sprinkled throughout were the walking sick: gaunt, frail, sallow-skinned men, unable to keep pace with the hurried throngs, sometimes escorted by a partner or caregiver, but mostly alone.

I got tested back in Los Angeles, but I was too afraid to get the results. I'd convinced myself that I was robustly healthy. I took vitamins and had a gym membership. Sometimes I even worked out. I rarely got sick, except for that ear infection that put me in the emergency room, or those annoying night sweats, and that weird spot on my leg that I continually obsessed over.

One day at Orphan Andy's in 1992, I turned away from a table of men who'd just placed drink orders. I froze as I realized that one of them was Al Parker. Just try to act normal, I told myself. Then I accidentally knocked down a tower of plastic glasses.

By the time their food was ready, I'd mustered enough courage to say, "Once I sold you a cock ring and a bottle of poppers." He and his friends laughed. Then Al Parker introduced himself by his real name—Drew. I introduced myself with the nickname I use among friends, Shane.

Returning to the kitchen, I heard someone call: "Shane! Come back, Shane!"

Drew was holding up his empty glass for a refill.

"Come back, Shane" became our running joke at Orphan Andy's. When anyone else said it, I grimaced. But when Drew said it, I got goose bumps. He came to Orphan Andy's often, though never alone. He was either with friends or with his partner, Keith, who had silver hair and serious crystal-blue eyes, like an Alaskan husky.

"Has anyone ever painted your portrait?" I asked Drew one day after taking his order.

He laughed: "Yes, as a matter of fact. Quite a few times." I thought of him sucking dick in that tree. Then he said, "You want me to pose for you?"

In my shock, I didn't know what to say. I'd never drawn from a live model before.

"I work from photographs," I said shyly. "I wondered if you had any pictures I could use, with your permission."

He smiled and said, "Sure, I might have something," and reached into his pocket and pulled out a business card. "Give me a call."

Thunderstruck, I took his card.

After I worked up the nerve to call him, he gave me directions to his place and told me it was the only lavender house on the street. There was loud barking when I rang the bell. The door opened, and a white dog continued to bark as Drew held his collar.

"He's friendly. He just wants to smell you."

Drew led me to the dining room where a picture window revealed a breathtaking view of the city. He was wearing a tank top and parachute pants. Even a billowing inseam couldn't disguise his massive bulge. His muscles were defined, but out of his jacket he appeared quite thin, almost frail.

"I'll be right back," he said, leaving the room. There was a book on the chair beside me: Living with Chronic Illness—A Physician's Guide.

Drew returned with a light box and hundreds of slides.

"Just pick the ones you want to use." He stood close as I put my eye to the viewer. In my peripheral vision, I saw him scoop the book off the chair and take it into another room, along with the dog.

"You know," I called out, "I'm not like a great artist or anything. I don't have any formal training, but I like to paint people."

"So," he answered, "paint me."

I looked at as many slides as I could. I wished he were still standing next to me. A lot of the photos were studio shots with other men. Al Parker oiled up at the beach, Al Parker in a truck, Al Parker in the city, Al Parker in the forest—always blissfully naked with his dick out.

After I'd made my selections, he saw me out the door. "Let me know when you're finished. I'd love to see it," he said. I was thrilled to have a built-in excuse to see him again—outside the diner.

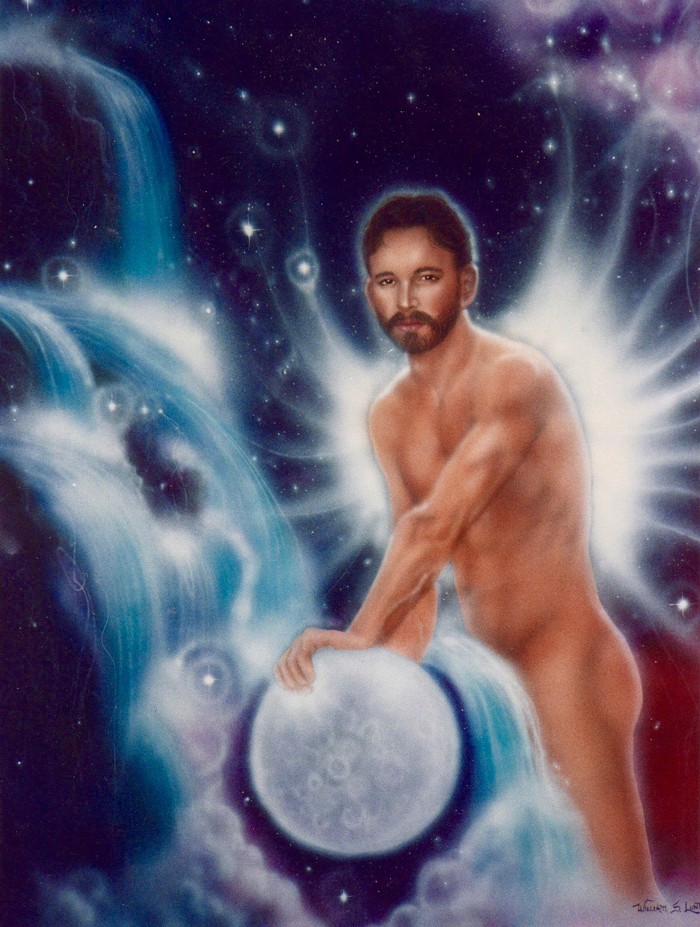

In my small apartment, I used my kitchen for a studio. After weeks of artistic performance anxiety, I turned on my airbrush and began to paint with air and ink. It didn't occur to me to wear a mask or open the windows. I thought I was channeling some divine cosmic force, but I was really just getting high on the paint fumes. Day after day, I'd return to that semi-lucid state. Time folded away. It took me a while to capture Drew's likeness.

Eventually, out of a dense fog, he appeared in focus.

"Hi," I said to his face. "Welcome to my kitchen!"

I surrounded him with cascades of aquamarine intergalactic stardust. Inspired by a card I pulled from a tarot deck, I also painted the moon. He was fucking the moon, looking like an archangel or a mythical god.

I got to Orphan Andy's that day with my fingers stained indigo, dusted with a fine splatter of white stars, just like in the painting. I was serving Ruby chicken soup when the phone rang.

"Shane, it's Keith, Drew's partner. I can't find Drew's wallet. Did he leave it there?"

I opened the lost-and-found drawer, thinking how awesome it would be if I found Al Parker's wallet. I could offer to bring it to their house and show them the portrait, too. I looked under the cash drawer. It wasn't there.

"Sorry, Keith, it's not here, but tell Drew I finished the portrait!"

There was silence.

"Shane, Drew died today. It was unexpected."

I didn't know what to say.

"Call me in a few days. I want to see your painting. You've got our number, right?"

"Yes, I do. I'll call you," I said, and hung up the phone.

I was still in shock. After telling Ruby what happened, I kept repeating, "I finished his portrait today, and now he's gone." That's how it was. Some men died suddenly. Some wasted away.

I looked at my hands.

"You've got a smudge on your cheek, too," Ruby said.

"I'm leaving it," I said. It was his sky.

A few days later, I took a cab to Drew's house to show Keith the painting. He held it against an empty wall in the foyer. A shaft of light from a window lit up the image of Drew.

"All it needs is a frame," he said. "We're having a memorial open house in a few weeks. Can I borrow it?"

I told him it would be an honor. Back at my apartment, I leaned the painting against the wall and wept as it beamed at me. The following day, I made an appointment at the clinic to get tested.

If I tested negative, I'd get a handful of condoms and be sent on my way. If I tested positive, I'd get an information packet—resources, treatment options, support groups. A slender man with curly hair entered the waiting room with a manila envelope and softly called out my case number.

He escorted me into a small room and closed the door. I'd assumed the worst, and I was right. On my way out, he gave me the number of a crisis line.

"Honey, take this," he said, reacting to my lack of reaction. "When the gravity of this sinks in, you'll want to talk with someone."

"Thanks," I said brightly. But all I could think about was how I could never tell my family. They can never know, I decided. I kept on walking, passing my apartment. I remembered a psychic lady on TV saying that they'd find a cure within three years. She must be a good psychic to be on TV, I told myself. I saw my reflection in a storefront window and was oddly comforted by the extra weight I'd gained. I don't look sick, I told myself, and 31 is too young to die. Then again, so is 40, the age Drew was.

The obituary announced the open house, and a lot of men, many dressed in leather, were lined up outside on the sidewalk when I arrived. I wasn't surprised by the big turnout. People had flown in from all over the county and even Canada to pay their respects. Inside, everyone spoke in a hushed, respectful tone, like in a chapel.

I wondered if Keith decided not to hang my painting, because I didn't see it anywhere—maybe it was too New Agey. Maybe he didn't like my frame. The line slowly proceeded into the living room. Two uniformed men stood guard on either side of a wooden box on a pedestal. It was Drew's ashes. The lid of the box was open, exposing a compartment filled with small personal items, including a cock ring and a brown bottle of poppers. Then the line funneled into the dining room, where Drew's close friends were gathered around the table. My painting of Drew was hanging on the wall behind them with potted ferns placed around it, like it was watching over them.

I eventually sold the painting to my friend Grant, who was Al Parker's scene partner in one of his last videos. Then Grant passed away.

I was still working at Orphan Andy's in 1996 when I read about the breakthroughs announced at the International AIDS Conference in Vancouver. Combination antiretroviral therapy was shown to reduce viral loads. A lot of us were skeptical after witnessing drug treatments fail so many people—drug treatments that not only didn't work but made the agony of dying worse—but over time, I noticed the obituary section shrink from several pages down to one. I've lived well past my 40th birthday. I never dreamed I'd live long enough to write a period piece about this time in our history and the important part a porn star played in my life.