That's a pretty bold statement in a city with a long and notorious history of anti-music politicians and policies. Remember the Teen Dance Ordinance? How about Mark Sidran's poster ban or his proposed noise ordinance, which club owners said was grossly punitive and would give police another tool with which to shut down their businesses? Sorry, Greg--Seattle isn't Austin. And it never will be.

Why is Austin known as the "Live Music Capital of the World"? Simple: Starting in the '90s, Austin's civic leaders made a serious commitment to put the city on the music map. And it worked: Today, Austin's civic commitment to music is not only unmistakable; it's near maniacal. Music is omnipresent in Austin--from the airport (where honky-tonk and country singers perform daily on three stages) to the Central Market grocery store (with a year-round schedule that includes bluegrass, samba, blues, and jazz), to Flashback vintage clothiers (where folkies croon outdoors on summer evenings). Whether you find it charming or irksome, music defines Austin. And it didn't happen accidentally--it took a serious civic and financial commitment, plus a regulatory structure that doesn't strangle music businesses before they have a chance to breathe.

The Teen Dance Ordinance may be dead in Seattle, but nanny liberalism is alive, well, and still stifling our music industry. Consider: Unlike in Texas, where minors can walk right into most clubs and bars, Washington State politicians "protect" kids by locking them out of clubs until they're 21. (All-ages clubs and shows are the only exception. In Austin, a hand stamp helps bartenders keep the kids and grownups separate.) The beer garden, where drinkers are corralled at outdoor events like Bumbershoot, is another bizarre Northwest innovation; in Austin, where the liquor regulations are still relatively loose, drinkers are free to wander, beer in hand, around outdoor festivals. Breweries, in fact, often provide free beer to lubricate sales at in-store performances like those at Waterloo Records, a staple of the local music scene. Dave Meinert, a Seattle music promoter who helped instigate the economic impact study, says he'd "like to see our music scene be about music," not drinking. But the fact is, drinking and music go hand in hand. Booze keeps clubs afloat; conversely, stringent liquor laws only serve to stifle the music industry.

In Austin, private groups like the Sims Foundation, which subsidizes mental-health care for musicians, and the two-year-old Austin Music Foundation (AMF), which runs a grant program called the Austin Music Incubator and an educational series, the Music Industry Boot Camp, give clubs and musicians the kind of support structure that Seattle musicians are still struggling to build. More important, perhaps, are Austin's 250 live-music venues, which are concentrated around rowdy, bustling Sixth Street and the surrounding downtown core. (In contrast, Seattle's 130 or so clubs are scattered from Ballard to Belltown to Capitol Hill, an ungainly arrangement that discourages club-hopping and keeps Seattle from organically sprouting a music district of its own.)

AMF cofounder Nikki Rowling says Austin's music industry "is based around the existence of the music venues and their owners, who are really dedicated to breaking new bands." When I told her about Nickels' bold plan to out-music Austin, Rowling could barely stifle a laugh. "[The] Austin [music industry] was built on a base of strong musicianship starting 15 years ago," Rowling says. "That didn't happen overnight." While Seattle club owners have a well-established history of promoting new and unknown bands, the sheer number of clubs in Austin does give bands more opportunities to have their music heard.

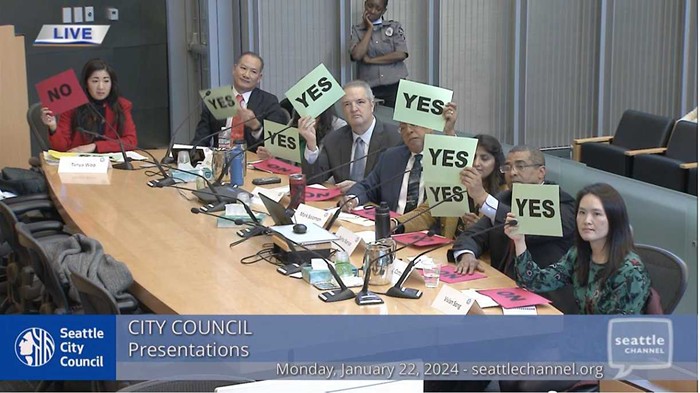

Austin's music industry enjoys another big advantage: The city government doesn't just sanction live music--it practically sponsors it. For example: Back in the 1980s, the city council created the Austin Music Commission, a nine-member volunteer organization that acts as a liaison between the music industry and city government. The commission isn't a token gesture. Despite constant budget pressure, it gets things done for local musicians. Last year, after musicians complained about unreasonable parking regulations in front of clubs, the commission convinced the city to let musicians load their equipment on Sixth Street between 6:00 p.m. and 3:00 a.m. They've also brought what music-commission staffer Brenda Johnson calls a "musicians' perspective" to an ordinance that would have banned smoking in bars and clubs and one that set noise limits at outdoor shows.

Musicians--and music lobby groups like JAMPAC--do this here, too, but their power is limited by the fact that, unlike Austin musicians, they don't have a city-appointed liaison lobbying for their interests at city hall. In fact, until recently, musicians haven't even had an office at the city devoted to addressing their concerns. (The Mayor's Office of Film and Music, which could serve a similar function, was only recently renamed to reflect Seattle's new commitment to pro-music policies.) Austin isn't a musicians' paradise (the noise ordinance passed, to the chagrin of several clubs that hold outdoor shows) but, as Johnson says, "There are lots of issues that the music community deals with that would probably just get ignored if there wasn't a music commission."

Johnson, officially an employee of the Austin Convention and Visitors Bureau, can rattle off a seemingly endless list of programs the city has backed to boost the local music scene: the $150,000-a-year Austin Music Network, a 24-hour local-music channel; the $250,000 Music Industry Loan Program, which guarantees loans for musicians or music businesses; Austin Energy's Commercial Rebate program, which helps club owners figure out ways to lower their electric bills. And then there's Johnson's pet project, the Hire an Austin Musician program, which encourages businesses to hire local musicians to entertain at meetings and business parties.

Seattle, to its credit, has done a lot since a failed mayoral bid sent Mark Sidran back to private practice in 2001. We overturned the Teen Dance Ordinance, adopted a noise ordinance that doesn't impact clubs, and kicked both Sidran and TDO queen Margaret Pageler to the curb. Nickels' study, the first official recognition of the music industry's impact on Seattle's economy, is a step in the right direction. As recently as a year or two ago, says Meinert, who helped spearhead the study, "we lived in an anti-music city. The music community organized and has turned it into a pro-music city. We kind of won."

Nickels' impulse--to encourage city policies that reduce the music industry's tax burden, improve traffic, and boost the development of more small music venues--is a good one. But whatever gains musicians make here, it's unlikely Seattle (with its outdated liquor laws and history of nanny liberalism) will ever be the new "live music capital of the world," as Austin was dubbed by city ordinance way back in 1991. As concrete evidence of that, you need only look at EMP, which has shed nearly half its workforce and slashed its operating budget since its heavily hyped opening in June 2000. Last year, the Northwest's flagship music institution announced a new focus: science fiction.