Welcome to the Ballard Bowl, part of the neighborhood's skate park. It's a small park--less than the size of a soccer field--and an even smaller bowl: taking up a 50- by 50-foot corner of the paved space, not much bigger than a modest two-car garage. But despite the bowl's small size, and immense popularity, the city may bulldoze it by this summer.

The little bowl, apparently, doesn't fit in with the neighborhood's plan for a quiet, grassy park on the site of the empty grocery store, a park that's been in the works since the late '90s, and is just months away from breaking ground. The bowl, those pro-park neighbors point out, was supposed to be temporary, until the city found a location for a larger, permanent skate park. But in the two years since the bowl was poured, the city hasn't secured a better spot, let alone opened a new, alternative skate park. Now, as the city's parks department gears up for the final approval stages of Ballard's long-awaited park, the skaters are about to lose their beloved bowl.

The bowl owes its existence to a few industrious teenage boys. Spying the empty grocery-store lot, they thought it would be perfect for a skate park--a couple of ramps, and maybe some metal rails to skid across. They were constantly being harassed for skating in Ballard's streets and sidewalks. They argued that building a skate park in the neighborhood would save Ballard's sidewalks and planters from skateboard wear and tear. Similar concerns for downtown's Westlake Center plaza prompted the city to build the Seattle Center SkatePark, also known as "Seaskate," near Seattle Center a few years earlier.

The idea soon caught fire: In 2001, the city granted the kids permission to turn a corner of the vacant Safeway parking lot into a skate park--temporarily, until a better site could be found.

Building the park, however, was no cakewalk. The skateboarders needed to come up with money to finance the construction of a concrete skate bowl--a $50,000 to $70,000 project. In DIY fashion, the skateboarders sold t-shirts and held fundraisers in Ballard venues like the Tractor Tavern; they also secured city Neighborhood Matching Fund grants. The park was nearly finished by mid-2001. Construction on the bowl, however, stopped when the city discovered a drainage problem. For a few months, the kids who'd gotten the project going were certain the bowl wouldn't be built and they'd be left to skate around a muddy hole in the ground. Luckily, through their hard work, the skateboarders won the sympathy of the parks department, which put two staffers on the project. Once the parks department got behind them, the skateboarders raised the last $19,000 and fixed the drainage problem. The bowl was finished on May 15, 2002.

Jason Harrison remembers the bowl's early struggles. A longtime skater, Harrison is now an underemployed tech guy with plenty of time on his hands. Harrison runs a popular skateboarder website, sleestak.net, where his fellow skaters know him as Bobcat. He's been involved with the Ballard Bowl for the past few years, emceeing at an early rock-and-roll fundraiser. That was about the extent of his political involvement, until this year. After a January meeting about the future Ballard park--a meeting where the skaters realized their bowl was on the chopping block--Harrison got to work, sending out a cry for help on his website. He scheduled a meeting for the following week, at a Capitol Hill coffee shop, to talk save-the-bowl strategy.

So many people showed up that Harrison had to lead his troops to a nearby bar instead. The crowd ordered a dozen pitchers of beer and spent the first half-hour ranting about what looked like an anti-skate-park mentality in Ballard. Faced with losing their park, the skaters were understandably upset--they'd always tried hard to be good neighbors, keeping alcohol, loud music, and drugs away from the bowl. They even managed to keep the park nearly graffiti-free. Now, despite all the work that went into building the bowl, and all the effort to treat the area with respect, Ballard's leaders seemed to be turning on the popular bowl.

"Let's see if we can start an organization, a watchdog force," Harrison told his supporters, who numbered around 30, at the initial meeting. That's how the Puget Sound Skatepark Association (PSSA) was born. The group set out two clear-cut goals: Save the Ballard Bowl, and urge the city to build more skate parks.

Meanwhile, back in Ballard, the neighborhood's chamber of commerce was starting to realize it had hit a snag.

The anticipated park--complete with an amphitheater, and metal sculptural elements that catch rain--had been on Ballard's agenda since the late 1990s, during the city's neighborhood planning process. "There was a lot of thought put into where Ballard [would] accept density," says the chamber's executive director, Beth Williamson Miller, from her cozily cluttered first-floor office on Market Street Northwest, two blocks from the bowl. As head of the only neighborhood organization with paid staff and an office, Miller is the unofficial spokesperson for the skate-bowl opposition.

She explains that the neighborhood designated a 12-square-block "downtown Ballard" area just north of Market as the density dumping ground. In exchange, the neighborhood wanted amenities to support the density, namely a large central park. When the Safeway relocated to 15th Avenue Northwest in 1999, leaving behind a large, centrally located property, the neighborhood pushed the city to make a bid. Developers jumped for the space, driving up the price up the price to $5.1 million when the city purchased the lot in March 2001.

Two years later, Miller is expecting 1,000 new residential units--condos and apartments--to spring up around the park site in the next few years. A new Ballard Library and neighborhood service center have broken ground. All that's left to cap off "downtown Ballard" is the park.

Miller remembers when the skate park project began: "Ballard signed off and endorsed the [city] grants, with the caveat that it was temporary," she says. But even then, some neighborhood leaders were concerned about what would happen in a few years, when it was time to build the new park. "You can say 'temporary' all you want, but the minute you try to take [the bowl] away you've got a problem."

When the parks department started holding formal meetings to design the neighborhood park, Miller says there wasn't a preemptive effort to make sure the bowl would be removed. The chamber, and other neighborhood leaders, assumed it would be. "To develop a whole park around something intended to be temporary seemed backwards," Miller says. Moreover, they argued, the bowl was loud and busy, and it put a squeeze on the already tight parking in Ballard. Plus, the owners of a QFC adjacent to the park property had just announced they'd finally go ahead with a much-anticipated redevelopment, which would include underground parking and also housing on top of a bigger grocery store. The plans call for two-story town homes to look out on the park--and the skate bowl, if it remains. Neighborhood planners feared the developer wouldn't want to build housing next to the bowl.

When the skateboarders came out full force to keep the bowl, and the parks department created two park designs that kept the bowl (and just one that didn't), Miller quickly fired off a letter to the mayor's office on behalf of the chamber and other neighborhood leaders--a letter that was published in the Ballard News-Tribune, whose offices are down the hall from the chamber in its building at Market and 22nd Avenue Northwest. Miller requested a meeting to get Ballard's neighborhood plans back on track. "The idea was, things have gotten away from the process we had with the city," she says. "Can we put on the brakes and revisit this?" They've yet to get a response from the mayor.

Skaters were happy to see that the bowl was included in two drawings. They were unhappy, however, that a handful of neighborhood representatives were insisting that Ballard preferred the bowl-free park option. Within days, the skaters were organized. Skateboarders--now joined by a volunteer public relations professional, Kelly O'Neill, who read about the PSSA's first meeting in The Stranger, lives in Ballard, and loves the skate park--drafted a rebuttal letter and sent it off to the mayor's office. They measured the noise from the bowl and found it quieter than a nearby QFC loading dock, and they argued that most skateboarders skate to the park or hop on the bus--they don't drive and park nearby. And even if it wasn't in the neighborhood's late-'90s plan, the skateboarders argued that the bowl was successful now--perhaps the plan had been shortsighted.

The battle in Ballard had officially begun.

In the middle of what will become the new park, an empty Safeway store has been the site of frequent tense meetings over the bowl's fate. The old store--empty since Safeway relocated--is falling apart. To get into the big fluorescent-lit space, which shelters everything from weekend farmers' markets to community theater, visitors have to use both hands to pry open the heavy glass doors. It was a meeting at the old Safeway in January that first riled up the skateboarders. A second meeting was held at the site on March 12--after two months of intense lobbying from both sides over the bowl.

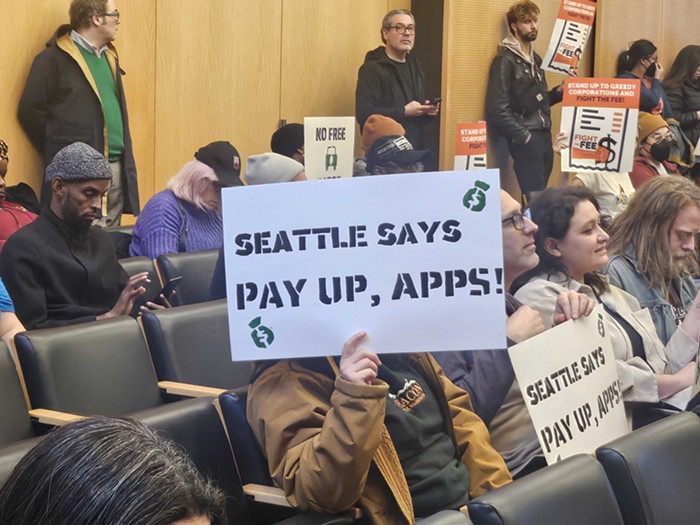

That night, city parks department staffers were slated to unveil their "preferred" layout for the new park. In the front, a few dozen people in favor of a grassy park were seated, quietly waiting for the presentation to begin. Filling the back rows of seats, and overflowing onto the sidelines, nearly 200 skateboarders and their supporters impatiently waited for the parks department to begin.

The skaters already knew which layout the parks department preferred: In a press release on February 27, Seattle Parks and Recreation Superintendent Ken Bounds announced that his staff would be recommending demolition of the bowl. The reason? A real skate park needs to be much bigger than the Ballard site can accommodate. "There's clearly a need for places to skateboard," said Bounds in the statement. "The heavy use of the temporary skate park in Ballard is evidence of that. I'm in the process of creating a Skateboard Advisory Committee to help us identify good sites to build them." He invited PSSA members to join the committee.

The PSSA agrees that Seattle should plan for more skate parks, but they didn't sign on full-force to Bounds' committee. Instead, the PSSA rallied folks to join them at the March 12 meeting.

The meeting was chaos. The cavernous room's terrible acoustics made it impossible to hear Cathy Tuttle--the parks staffer in charge of the new park--talk about the chosen design, which, she pointed out, included a small skating element with rails. It didn't help that the skaters in the back--tired of being ignored in the Ballard planning process--took every opportunity to heckle Tuttle. "Where's the bowl?" skaters yelled as Tuttle gestured to an overhead projection of a green, grassy park. At one point, a scuffle nearly broke out: A middle-aged man who said he'd spent seven years planning the new Ballard park was confronted by a mom who enjoyed bringing her son to the Ballard Bowl. Skate park supporters crowded around the pair, who argued over who had the right to decide how to design the park. A Seattle police officer--a rare sight at a park design meeting--edged in closer as skaters began firing questions at the neighborhood-plan guy. Was Ballard giving in to the QFC developers? Did the chamber realize it was out of touch with the young people in Ballard? What's his real problem with skateboarding anyway?

Seattle is notoriously unfair to its youth and hostile to the urban culture they help create and sustain: Witness the years-long battle to dump the obnoxious Teen Dance Ordinance. The TDO was finally dumped in August 2002--after a 17-year-long battle--and replaced by an All Ages Dance Ordinance, which has opened up the music landscape to teens. These days, other than music, it's hard to see what Seattle has to offer teens by way of entertainment. "We don't provide enough activities for youth and young people," Seattle City Council President Jan Drago says. She's signed the PSSA's petition to save the bowl.

"Seattle has been moving steadily away from being a kid-friendly place," says Seattle City Council member Peter Steinbrueck, who is raising two kids here--including one who begged for a skateboard last Christmas. "And that needs to change. Skateboard parks are a great amenity."

The skateboarders agree. The city, they point out, has just one other skate park besides the Ballard Bowl, Seaskate, near Seattle Center. Meanwhile, Vancouver, BC, and Portland each boast six in-city. Seattle has a lot of catching up to do.

The city's parks department admits that Seattle needs more skate parks, and crafted a policy last year to lay out the parameters for building civic skateboarder havens. Even the Ballard Chamber of Commerce and other neighborhood leaders claim to be skate-park-friendly--as long as skate parks aren't built in their neighborhood's downtown. "We feel very strongly that the skateboarders deserve something better than they were getting," says Miller, who wants to bring Harrison and the PSSA to the table to talk about supporting different sites for a bigger, better skate park, like a large space on Holman Road Northwest, near a Dick's Drive-In. PSSA members have also met with parks officials about sites near Green Lake, and under the Ballard Bridge. But the PSSA isn't willing to give up its fight to save the Ballard Bowl in the hopes that the city might build a new park in a few years. (The city has a bad track record with these sorts of promises: When the city banned postering on telephone poles in 1994, it promised to install kiosks all over town for posters. The kiosks never materialized.) Losing the Ballard Bowl before a new skate park is constructed would mean going without a park in the interim, a solution that won't work for skateboarders. At a bare minimum, the PSSA would like Ballard's "temporary" bowl to stay in place until the day the city opens a new skate park to replace it.

The PSSA has scheduled a meeting with City Council Member David Della--chair of the council's parks committee--for April 8. The group already brought Della out to the bowl to see it for himself. He asked few questions while he was there, instead letting the skateboarders make their pitch. Della hasn't committed one way or another--his aides say he's still exploring the issue--but the skateboarders hope they can sway the freshman council member. It may not matter, however: The council isn't sure it'll be asked to weigh in on the Ballard park design, unless it needs to make a final approval on funding the project. Della and Drago are both looking into the council's role. Steinbrueck hopes the neighborhood can work things out on its own.

The skateboarders also have a meeting planned with an aide in Mayor Nickels' office. Even if the park doesn't make it onto the council's agenda, Nickels can step in: He's parks superintendent Bounds' boss. After the PSSA sits down with Nickels' aide, it has plans to catch the mayor's eye at an event on March 27. The mayor will be in the area as part of a neighborhood cleanup, and skateboarders plan to show up, work gloves at the ready, to prove they're good neighbors.

Permanently integrating the popular bowl into the new Ballard park seems like the best compromise--for the skaters and the neighborhood. The skaters aren't the only ones who hold that opinion: Plenty of the neighborhood's senior citizens have signed their save-the-bowl petition, because they enjoy walking to the skate park and watching the skaters. A few dozen Ballard businesses--some of them chamber members--have signed letters supporting keeping the bowl where it is.

Keeping the bowl would enhance the "eyes on the park" idea behind building housing that overlooks the green space. Since there's almost always someone at the bowl, the constant use of the park would deter illegal and unwanted activity. As for the worry that no one would want to live right next door to the park, folks who move into a town home next to a skate bowl that the city is committed to keeping in place would know what they were getting into. Some buyers might choose to live near the bowl because they skate, or their kids skate. Retail is planned for the lower level of the housing complex--it's not hard to picture a sidewalk cafe right next to the skate bowl. People could sit at the cafe in the summer and watch skaters do their 180s and fakies, while hungry and thirsty skateboarders pop in and out all year long, spending their money and keeping the cafe afloat.

It's likely the battle over the bowl will continue into May. The parks department's board of commissioners--a volunteer panel that represents the city at large on parks issues, like design--has a public meeting scheduled for April 8 to address the Ballard park. Anticipating a larger-than-usual crowd, the board has moved its meeting to the cavernous South Lake Union Armory at 860 Terry Avenue North. In May, the board will make its official recommendation to Superintendent Bounds, who has final say (barring council or mayoral intervention). The PSSA plans to keep fighting--it held a fundraiser on March 6 that netted nearly a thousand dollars, and there's a "Skate Jam" planned for April 3, featuring bands like the Gloryholes and Me Infecto.

Back at the chamber's Market Street offices, though, Miller is starting to tire of the fight. "In a community that normally is very relaxed and everybody pretty much gets along," she says, "it saddens me that there are any feelings of animosity." She's working on a letter to the PSSA to try to find common ground. "If we would all get together, we could come up with two magnificent parks, rather than one where everybody gets a little of what they want. We really do want to work with them."