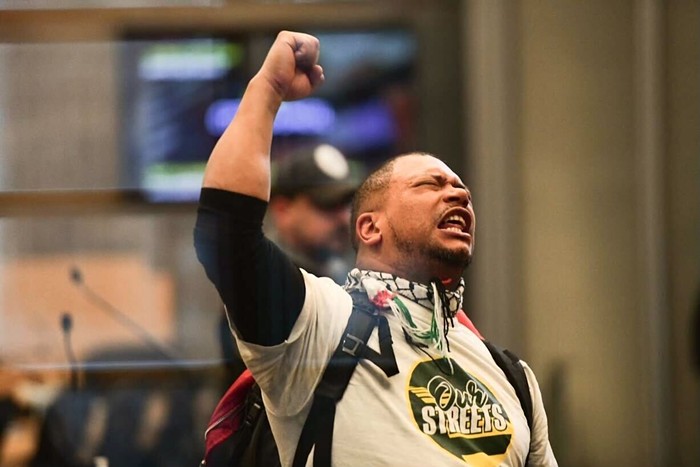

Seattle skaters are about to have one less place to grind. Four years ago, frustrated with the city's lack of skateparks and city leaders' glacial response to community demand, neighbor-hood activist Kate Martin spent over $15,000 to design and build a spot for her two sons—then 11 and 13—to skate in their own front yard [see "Skate Mom," Amy Jenniges, June 2, 2005]. The thousand square feet of cement ramps and rails that flow across the front yard of Martin's Greenwood home—with warped-but-clean lines reminiscent of a Frank Gehry building—drew throngs of neighborhood kids whenever the pavement was dry enough to ride. "People were stoked about it," Martin says. "It's something good for the kids."

But as Martin's skatepark became a hit among neighborhood kids, it also drew the attention of the city, since part of it was built on city property without permits.

In October, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) sent Martin a letter ordering her to demolish the portion of the park that sits on the city-owned planting strip. Although 80 percent of Martin's skatepark is on her property, an 18-foot-long, 2-foot-high half-moon-shaped concrete wall—which Martin refers to as a "clamshell"—covers most of the parking strip in front of her house. The city wants the clamshell gone, but removing it, Martin says, would compromise the safety of the skatepark. "The thing they want us to take out... protects kids from launching into the street," Martin says. "It's not like I can just take out the clamshell and call it good."

On May 15, the city attorney's office filed suit against Martin and her husband, Jose Chavez, slapping them with a $500-a-day fine backdated to October 6. Over the months, the fine added up to over $100,000. "It's some pretty deep doo-doo we're in right now," Martin says. "My thing is to cut my losses completely. I'm not there to make a point. I don't want to have to move out of my house."

SDOT spokesman Rick Sheridan would not comment on Martin's case. However, he was willing to discuss the city's recent changes to planting-strip regulations, allowing neighbors to make certain improvements without permits.

"Under the new rule changes, you are allowed to make improvements like gardening without a need for permit or a fee," Sheridan says. But "if you were to make hardscape improvements"—like a skatepark—"you'd need a permit."

However, SDOT seems less than stringent in its enforcement of the rules Sheridan cites: Within a block of Martin's home, two neighbors have cemented basketball hoops into their planting strips, which is illegal without a $251 permit.

This isn't the first time Martin and the city have been at odds. Over the years, Martin has butted heads with SDOT over the city's Pedestrian Master Plan—Martin says she received lots of pushback after asking the city to divert more funds to street improvements for cyclists and pedestrians—and the lack of sidewalks in her neighborhood. She's close friends with Andrea Okomski, the wife of city council member Nick Licata, who sued the city after her son, Josef Robinson, was struck by a car and badly injured at an unmarked crosswalk. Martin was widely viewed as a proxy for Okomski on the Pedestrian Master Plan Advisory Group, where she was a staunch advocate for increasing the number of marked crosswalks in the city.

Martin's advocacy work hasn't won her many friends at the city, and although she says she doesn't know whether SDOT's suit is meant as retaliation, she's resigning from the dozen or so community boards she serves on, including the Greenwood Community Council, Piper's Creek Watershed Council, and the Pedestrian Master Plan group, in the hope that the city will back down on its suit.

Martin hopes that the parks department can somehow take control of the skatepark and make it the first of the city's long-planned skate dots—small skateable parks and art features around the city. The likelihood that the parks department will assume responsibility for a skatepark that's mostly on private property seems remote, but several local skating advocates are going to bat for Martin.

"This use of space is the best way for us to get skateable elements scattered through the city," says Ryan Barth, president of the parks department's Skateboard Park Advisory Committee. "This is a model for what the city should be doing."

But Martin is not expecting a last-minute reprieve. She's already gotten the permits she needs to demolish the park. "The fine's still going up at $500 a day," she says. "I'm waiting on hearing from [the parks department] and then I'll send my husband out with a jackhammer, and that'll be that." ![]()