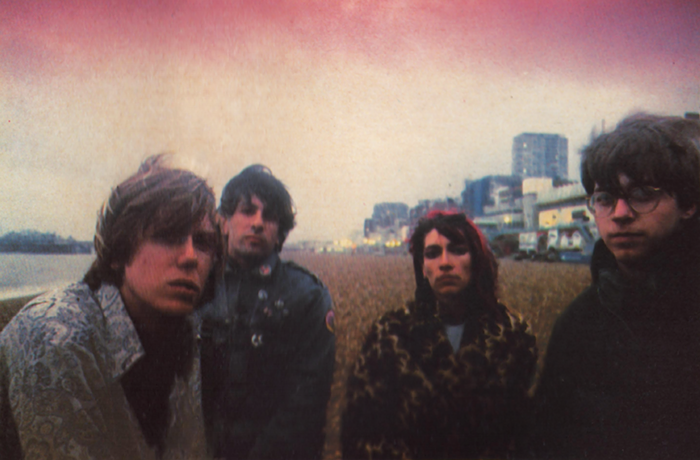

Rocket from the Tombs

w/the Catheters, Miminokoto

Sat Nov 22, Graceland, 10 pm, $10 adv.

Like many a long-lost cult band, Rocket from the Tombs' story is 90 percent myth, 10 percent hazy memories. This much is solid. One June in Cleveland, in 1974, David Thomas (later AKA Crocus Behemoth) and bassist Craig Bell refashioned their nascent bar band under a new name with guitarist/poet Peter Laughner. Then Gene O'Connor (AKA Cheetah Chrome) answered an ad, and the "classic" Rocket lineup went at it full force--for about eight months, with a few different drummers over eight gigs, ending up with a few cassettes for proof. Talk about your cometlike flameout.

Two subsequent offshoot bands--Pere Ubu and the Dead Boys--went on to some fame and cemented influence status. Laughner moved to the Big Apple and tried to join Television. But pulling a gun on their singer put the kibosh on that. "He was just showing them the thing, no big deal," explains Chrome. "Those big-city guys can't take it." Laughner eventually pulled fewer guns and way more corks, and sadly died of liver failure in 1977, at the age of 24.

But something funny happened on the way to oblivion. Those quickie Rocket recordings survived and made the underground noise aficionado tape trade rounds for decades. A notorious 1990 vinyl bootleg, Life Stinks, now fetches big bucks on eBay. Says Chrome, "It was cool to see the re-interest in the '90s. But Crocus was sick of seeing these crappy bootlegs. He tracked down the original tapes, and it turned out they were in good shape." Smog Veil Records has now finally released the first official Rocket from the Tombs CD, The Day the Earth Met the Rocket from the Tombs.

Consisting of live and 8-track recordings, this record attempts to re-create what might have been Rocket's debut album. And as the liner notes imply, if a proper debut had been unleashed in 1975, who knows what would've happened?

Certainly there was a zeitgeist floating around then, and the Rocket members had caught wind. As Chrome remembers, "Cleveland was a great place for being overwhelmed by music. We saw the Velvet Underground, then later the Stooges, Alice Cooper, MC5, Roxy Music, Bowie, alla that." But the music on The Day the Earth, while in on that séance, is a whole different spook. There's a desperate destruction that cranks through every tune, Thomas' voice squealing with a gawkish terror not found in the disaffected stance of many of the new wave singers. Laughner and Chrome's guitars don't play off as much as slay off each other, culminating in "What Love Is," with slashing guitar shards flying like shrapnel. And there are the dramatic ballads and a lyrical sarcasm about their apocalyptic visions that are pure wise-ass Cleveland.

Rocket, and in some measure their similarly dustbin-tossed Cleve-O cohorts of that era, Electric Eels and the Mirrors, have come to represent for many the match strike for the entire worldwide punk rock explosion of the 1970s and beyond. Theirs is the biographical plotline for the curious way in which rock 'n' roll's post-'60s innovators are often doomed to obscurity by their birth in out-of-the-industry-loop locations, their volatile crash-up of the genre (usually brief in existence), and a subsequently long-simmering legend born of blurry Mythic Tales.

Since he was long perceived, right or wrong, as the heart and soul of the band, any idea of a Rocket reunion without Laughner seems blasphemous to purists. Thomas retorts, "Look, don't come. I don't care. No band is any one person. Anyway, we're not re-forming. There's no new material. We're all losing money on this. We just like the chance to play the songs again." And as Chrome points out, "We did get [Television guitarist] Richard Lloyd to join us for this. He played with Peter a bit, so we're trying to grow into some of Peter's parts. He was an amazing guitarist. I loved the guy. It's a shame what happened."

It would be wrong to just simply resign such stories and sounds to a "punk forefather" asterisk. Plus it's well established that Rocket was an art project--tales of dressing up in all tinfoil and exploring Beefheartian freakouts was the norm. "That's why I describe punk rock as counterrevolutionary. Punk wanted to stop growth," says Thomas. "For us, all the bloated stadium stuff of that era wasn't incentive or disincentive, it was just another world we never even thought about entering. Our attitude was shaped by the situation we found ourselves in."