The big story about Lucas Debargue, who is performing Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 4 with the Seattle Symphony through tomorrow, is that he took last place (4th) in the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow last year, despite the fact that he split the judges and was clearly the crowd favorite. Those who loved him loved his passionate intensity at the bench, his innovative interpretations of pieces, and many were moved by his backstory, which we'll get to in a second.

The decision at the Tchaikovsky Competition ended up being one of the most controversial judgments in the competition's history.

Several of the judges wanted to give him second or third place so bad that they threatened never to judge the competition again unless they got their way. Their enjoyably snippy rebukes are delightful to read.

If you win first place in the "Tchaik," the deal is you're considered the newest best piano player in the world. Record companies give you contracts, you start making the rounds on tours, Russian dignitaries and bloggers fawn over you. Because nobody plays like him, because he's so unorthodox, all of that stuff is now happening for Debargue, even though he only took last place.

The fact that Debargue even got to compete in the first place began with a coincidence. According to the Seattle Times, Debargue had an on-and-off relationship throughout grade school and high school. He had been playing in a rock band and working at a grocery store when a famous Russian professor saw him play at small town recital in France. She scooped him up, trained him up, and in four years he was playing at a world class level. This means he only started formal training at 20, which is obscene considering that most concert pianists start playing when they're four years old.

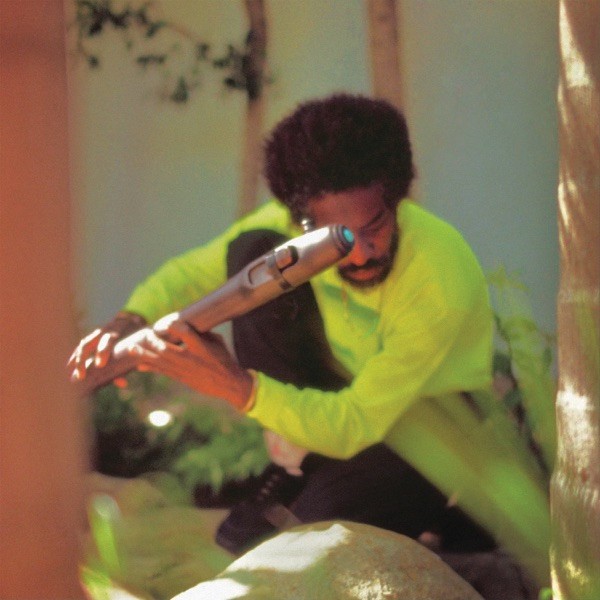

Like many who have emerged from rough or nontraditional backgrounds, I got the sense that Debargue was more interested in talking about the music he plays rather than the past he escaped. Though I didn't end up sitting for a haircut with him, I did grab a coffee with him BEFORE he got his haircut, and we had a spirited discussion about playing for dictators, and also the role of music in politics and life.

Behold the intensity:

Where do you fall on the spectrum between pianist as technician and pianist as artist?

I would prefer to see myself as an artist, a musician. Otherwise, I would feel pretty bad. Of course there is a technical part, but artistry is the greatest matter. For a musician, the music should never stop. Ideally you're always carrying the music with you. When you sleep, when you make love, when you go for drinks with friends, when you walk. Always the music has to have a part in your life.

And of course I need to feed my soul with great books of literature, paintings, cinema, and just great conversations about philosophy—I need this.

Philosophy? What kinda philosophy are you into?

I'm attracted by the baroque philosophy. In terms of the artist I like the idea that we are two beings at the same time. The social being who is walking the street and paying taxes, and then the tragic being who is looking for something beyond. God, personal achievement, whatever. It's like being on two different sides of a mirror, and we're able to swap from one place to another. This is the life of the artist.

What's your style?

Styles are defined by listeners—critics or historians of the music. For players, it's always the same story. You discover a score. And you have to manage to have some time alone with the score, to get progressively contaminated by the score. It has nothing to do with the style or the period. Style is a boundary—it would stop you from doing something. I pay attention only to what comes to my mind in the moment.

You played for Putin?

I didn't play for him privately. I was invited to play at the gala concert in the great hall of the conservatory after the [Tchaikovsky] competition ended. I was asked to perform a short piece. Putin was present. And yeah. I did my job. I did my best as I always do. There was nothing special. Of course it was special to know that Putin was there. There was security. People were excited. But me, I did what [I always] do.

From our perspective, Putin is an oppressive dictator. Did you feel weird playing for a dictator?

Not at all. In this kind of occasion, the music rules. The music is leading. Putin was in the place of the listener. He was not onstage. He listened like the others, was man like the others. Of course he did a speech before, but I didn't attend the speech. Me, I was just playing my part in the game.

What did you play?

It was a small piece of Tchaikovsky, "A Sentimental Waltz."

Does your audience change your approach to playing?

No. Music is universal. In fact, it is very important for me to be contradictory. Because for me, to reach the truth, the best way to express the truth in some ways is to find the best way to express the contradiction. Because truths always contain contradictions. I am a classical musician. Some come to see me expecting the frame of it. Part of my responsibility is to preserve this frame, which is out of my conception. But, of course, if the thing is great, then everyone is satisfied in the end: the people who are looking for the frame and the people who are waiting for true emotion. This is my job, this is why I love it, because at the same time you can satisfy Putin and you can satisfy someone that has absolutely to do with power by doing exactly the same thing.

Hm.

I cannot part myself and play for one or the other. I can only focus on the music-making.

I see. But no part of you was like, "Fuck this guy."

No.

Because the music transcends the politics?

Absolutely. This is my point. When Putin put himself in the position of the listener, at that moment he was not the master. I think it's good. It's good when the machine stops so we can take a breath of something else.

Wasn't a composer like Shostakovich using music to fight against Stalin?

It's not that easy. Even in dictatorship there's not just one man leading. It's like—there are communities spying on other communities, everyone is frightened by the other, and it's a very tense state. Shostakovich was taking all this tense energy from the people, these fears, this very strange climate, and he was taking inspiration from it.

We just elected a xenophobic demagogue to the highest office. Is there anything in the music you're playing this weekend that speaks to that?

In music like in all other arts there is a kind of catharsis. The music can help people to get wild, and to clean their soul of the shit that can remain there. The problem is that if people forget about art and the utility that art can have in real life, then they let some part of their soul rot. We all have violence inside, we're all looking for trouble, in a way. But if you deal in art that deals with contradictions, then you will be much more temperate. Populism is just one man shouting, "I WILL BRING WHAT YOU'RE EXPECTING." One note.

Hah!

But I'm sure that you cannot ask someone to clean your problems for you. If people have problems with xenophobia, they have to examine themselves. It's a personal problem. Of course people are ashamed of that. And so they ask a character—a cartoon character—to be a representation of their sins.

You know, I decided to become a professional musician because I thought it was the only honest thing I could do.

It was the only thing you were good at?

If I'm being completely honest, yes. I wanted to develop this strength instead of going toward weaker points and to say "Oh, I have to better at that." But now. I still think about it. I feel like we all have some kind of strength. We can do almost whatever we want nowadays—as soon as we can afford a living standard—but then we have a choice to go for our stronger points or to spend all our time trying to work on our weaker points. I think deciding which to pursue is the most important decision we make.

I like that. You wanna get a haircut?

Of course, if there's still time.