If you've read the stories about kids attending remote school in parking lots just for the wifi, then you know Washington fails to live up to its reputation as a tech hub when it comes to actually connecting people to the internet.

The problem remains especially salient in "unserved and underserved communities," which is the phrase politicians use when they mean rural and urban areas that internet providers refuse to serve because it's unprofitable to do so.

Though most people conceive of broadband internet as an essential service in the 21st century, and though our reliance on speedy connections will only increase in the post-pandemic future as companies continue to push their employees to work from home, the private sector's profit motive makes the goal of universal broadband impossible to reach. Running new fiber out to rural areas and offering steep discounts on reliably fast service to low-income families doesn't fatten the fattening wallets of telecoms, so rural areas will stay disconnected, and broadband will remain out of reach for the poor.

(That said, in 2011 Comcast did launch its Internet Essentials program, which offers cable internet for under $10 to people with low incomes who qualify. The company recently faced criticism about under-delivering on promised speeds. This month the company raised its download speeds, but, of course, Comcast doesn't cover everywhere, and it's unclear if consumers will really see the increased speeds.)

This year lawmakers in Olympia want to solve these problems by essentially offering a public option for broadband. State law currently prohibits public entities such as public utility districts (PUDs) and ports from jumping into the retail broadband market for dumb reasons we'll get into later, but bills from Democratic Sen. Lisa Wellman (SB 5383) and Rep. Drew Hansen (HB 1336) would grant those entities retail authority, allowing them to apply for big federal grants to fund the expensive task of transforming Washington into a gigabit state. (How expensive? Betty Buckley, executive director of the state's independent telecommunications association, put the number at $5 billion.)

The two bills, however, are not alike. For one, Hansen's bill also grants retail authority to counties, cities with populations under 10,000, and towns. For two, Wellman's bill hands private companies veto power over public entities who want to expand into their territory or build in areas where those companies say they plan to expand.

Comcast, small telecom companies, and the business lobby back Sen. Wellman's much more limited proposal. Meanwhile, ports, PUDs, rural health clinics, the Suquamish Tribe, parents, teachers, broadband activists, and over a thousand citizens who signed up to testify for the bill support Rep. Hansen's proposal. One Republican has signed on to each of the bills, which suggests some bipartisan support for the idea. Both bills currently sit in committees in opposite chambers, setting up a fight for which approach will win out.

Future-proof

Before we discuss the different approaches, let's review some terms and players, and lay out some of the relevant history, otherwise the issue becomes difficult to follow.

As with all things in America, our broadband is built on old skeletons and split into public, private, and public-private arenas.

Private cable and telecommunications companies such as Comcast, CenturyLink, and Frontier top the list of internet service providers in the state. Smaller telecoms serve places outside of town. Though multiple providers exist, the companies tend to cut out turf to minimize competition. These companies built and inherited a web of lines that deliver internet through copper wire (DSL), coaxial cable, or "glass" fiber. Companies like Viasat and HughesNet also offer broadband internet via satellite, and others provide fixed or mobile wireless broadband. (Elon Musk, a billionaire shitposter who's going out with Grimes, is exciting some with his Starlink satellite broadband technology, though we'll see if that pans out.)

Of these options, some public broadband advocates call fiber "future-proof" because it offers the fastest and most reliable service, with 1 gigabit-per-second upload and download speeds. Cable and DSL generally offer lower speed caps. You can achieve FCC-recommended broadband speeds for telecommuting or gaming or streaming amateur porn festivals through any of these modes, but advocates argue the FCC recommendations are too low given our growing data needs. Plus, consumers say satellite can be kinda spotty, and speed claims from cable and copper sometimes aren't as reliable as promised.

That's all for the private side. On the public side, we have PUDs and ports.

Ports build and operate airports, marine ports, railroads, and industrial areas.

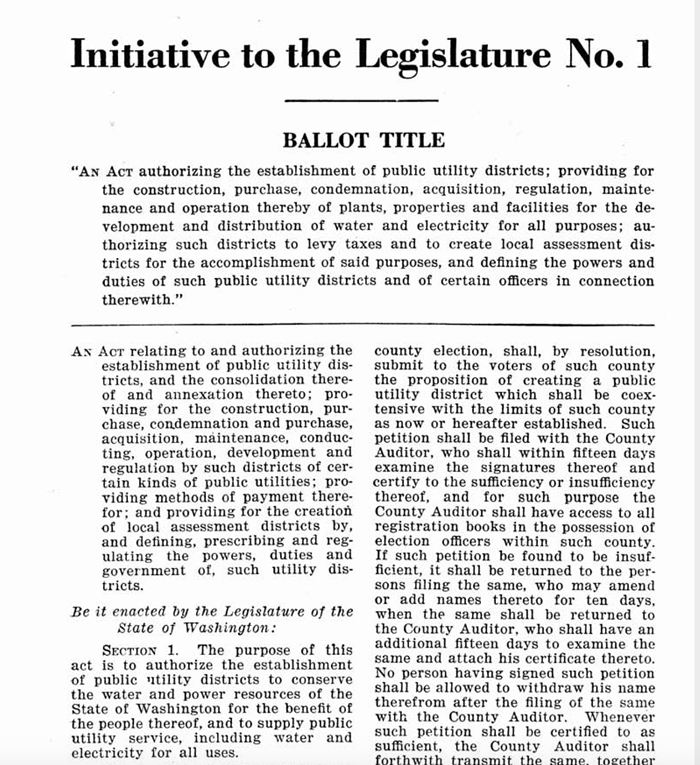

PUDs arose, as the incredible public-access-style video above mentions, after private companies failed to extend essential utilities such as electricity and water out to rural areas for the exact same reason that they're failing to extend broadband to those areas today. In 1930, the Washington State Grange, a populist and yet also kinda isolationist agricultural group, cooked up the first-ever initiative, gathered a bunch of signatures, and ultimately created the PUDs, which are utility co-ops run by elected commissioners.

The state now has 28 PUDs, and they offer whatever voters in their districts want. Most provide electricity, a lot of them provide water or sewer services, over half already provide wholesale telecommunications services, and one provides natural gas. The PUDs who provide electricity build their own poles and lay out their own lines, and they either generate the electricity through their own dams or buy it from the Bonneville Power Administration. (Energy and telecom PUDs can make a good pairing because both services require the same thing: utility poles and wires.)

A need for authority

The big difference between the public and private entities is that Washington only authorizes the public entities to provide wholesale internet services. That is, the law allows PUDs and ports to build internet infrastructure, but they can't sell directly to you, the "end user." (Selling directly to "end users" is called "retail authority.") Only private companies can run that "last mile" of wire to you, even when that last mile is only a few feet.

(One exception to this rule is the Kitsap PUD. In 2018 the Legislature granted Kitsap very limited retail authority, which means the public utility can step in to provide service if a private company drops out or fails to deliver the service they say they'll deliver. So far, they've had success expanding broadband to more affluent rural areas that petition the PUD for service and commit to paying for the build over time, but low-income neighborhoods can't afford that, so they still struggle.)

Without full retail authority, these public entities cannot apply for over 20 billion dollars in federal grants aimed at extending broadband to underserved and unserved areas. Those grants include the FCC Rural Development Opportunity Fund ($20 billion), the FCC Lifeline ($2 billion), the FCC Connect America ($1 billion), and whatever ends up in the next relief bill. Private companies, however, can already apply for these grants, which is nice for them. PUDs and ports see the ability to compete for this money as a key way to overcome the high cost of running fiber out to sparsely populated rural areas, and to building out capacity in urban areas where high costs create a barrier to access.

Washington's restrictions on public utilities and ports are dumb

A majority of states have no restrictions on public broadband, and people in those states tend to have more access to cheaper broadband as a result, according to Broadband Now. Meanwhile, a 2020 study published in the journal Telecommunications Policy found that "municipal/cooperative restrictions decrease general broadband availability by 3 percentage points."

Washington imposed its restrictions on public providers back in 2000, when the internet graduated from college and started looking to grow its networks. Back then, some PUDs and ports, especially those who already owned utility poles, started laying down internet infrastructure, but there were some legal disagreements about whether they had the authority to sell straight to homes and businesses.

Long story short, when the public entities went to the Legislature to get that authority, telecom companies lobbied to limit it in statute, ensuring the bill that passed "expressly prohibited" publics from "providing wholesale telecommunication services to end users."

Judging from testimony in the House and Senate companion bills on the issue, and from testimony in subsequent bills to offer public entities retail authority, Comcast lobbyists argued that granting such authority would make competition "unfair." Because public entities don't require quick returns on investments, they can stretch out costs over time and advertise lower costs for faster service. Private companies can't do that.

Telecom companies also don't want to pay what they consider unfairly high fees to run their internet service through public broadband infrastructure. If they don't own the poles, then they gotta pay the "pole attachment" fees, and they hate that. Back in 2007, Comcast, CenturyLink, and Charter deliberately refused to pay Pacific County PUD No. 2 after rates rose, and then just left their equipment up on the poles. The PUD sued and won, but only after a 12-year court battle.

After years of bickering and gridlock over pole attachment reform (lol), the Legislature started making some progress toward expanding broadband. In 2019, Sen. Wellman passed SB 5511, which codified internet speed goals in state law, set up a state broadband office to develop strategies to meet those goals and also to draw up a better map of current service (because the federal maps are "ludicrously dreadful"), and started the Public Works Board to provide loans and grants to a variety of public and private utility providers. They've funded over 2,000 projects already, but their $3 billion pool isn't just reserved for broadband expansion.

The question now remains: Rural and urban areas have been waiting for 20 years to log on to fast, reliable internet service. How much longer should the state keep them waiting, especially given the pressures imposed by the pandemic?

To object or not to object, that is the question

Rep. Hansen's bill simply gives the ports, the PUDs, the counties, the towns, and the small cities the retail authority they want. He views the service as a public option. If building out to rural areas and offering deep discounts in the city doesn't pencil for private companies, then, no prob! The ports and PUDs were built expressly for those purposes, so let's give them the ability to grab federal grants and give people a cheaper option, or else to build the infrastructure to increase competition in the region.

Unlike the House bill, the Senate bill gives the publics retail authority, but it also gives private companies a kind of veto power. If a PUD or port wants to build in an area where a private company already provides services, or where a private company promises to provide services within six months, then those companies can object to the public entity expanding broadband there.

Wellman argues this veto power will prevent "overbuilds" and encourage the public entities only to build infrastructure where we don't currently have it. Over the phone, Wellman argued that her bill focuses in areas with the greatest need, while Hansen's bill "just blows up the marketplace," you know, the marketplace that has yet to provide adequate internet to underserved and unserved areas despite sucking up hundreds of millions of tax-payer dollars to do just that.

She also raised questions about whether PUDs and ports would really use this authority to build into rural areas. "They say they want to. They want to be able to serve unserved areas that have wells and septic tanks? They’re not serving them now! Time after time we’ve seen people go where the market is," she said.

She continued: "I think the House bill sounds great. Who wouldn’t want everything? Broadband for all. But I don’t believe that’s what you're going to get. It’s not where the market is. There's no carrot there."

Wellman also added her bill was "well supported by the Governor and the broadband office," which suggests her bill will be easier to pass.

In his testimony in favor of the bill, James Thompson, executive director of the Washington Public Ports Association, said "we’re absolutely willing to serve unserved and underserved areas."

In an email, Kitsap PUD commissioner Debra Lester, who testified in favor of the House bill, responded to Wellman's claims point by point.

Lester first took umbrage with the fact that bringing "broadband fiber with the option of a gig symmetrical into a community where currently there are only private internet providers with DSL and cable" could even be considered an overbuild. "This is building future-proof infrastructure," she said.

Lester added that PUDs are "hardwired to serve their communities," and the private veto power would only "slow down public broadband deployment and give private corporate internet service providers the opportunity to lodge challenges against all broadband grants/loans to public entities." She pointed to conflicts between publics and privates in Alabama, where privates challenged 14 build proposals based on "overbuild" claims, some of which the publics found dubious.

Another problem is that companies base overbuild claims on FCC maps that purport to show where internet already exists. But broadband supporters argue that the FCC maps suck. First off, the FCC bases their mapping on self-reported, proprietary data from telecom companies, so it's hard to verify. Then, the FCC shows the data by census block, which often isn't granular enough to accurately map varying internet speeds in the city or in the country. During testimony on the Senate bill, George Caan, executive director for the Washington Public Utility Districts Association, said that "communities don’t agree the service they’re being told they’re getting is the service they’re actually getting."

The state broadband office, however, is working on its own mapping initiative. That project will help, but it'll take some time. (You can do your part by participating in their annual speed survey.)

Map vagaries aside, Lester said the mere existence of private wells and septic tanks in rural areas doesn't suggest that PUDs and ports won't follow through on their promises to build out broadband to those areas.

"That's simply a misunderstanding of water systems," Lester said. "Private wells were established quite some time ago. Many people like having their own well system that they do not have to pay utility costs on. Kitsap PUD, though, has taken over many failing private water systems and wells. We do so when communities petition us to do so."

At the end of the day, Lester argued, the public entities have little interest in competing with or undermining private companies, as they work with private companies within their own broadband networks and believe more competition is best for consumers. Their goal is to get full authority to "access federal funds to support all people to connect to adequate broadband services."

Both the House and Senate bills passed their respective chambers, so discussion on the issue will continue next week. The Senate Energy committee has scheduled a hearing for the House bill on March 11.

If you want "broadband for all," to use Sen. Wellman's language, then your best bet is telling Energy committee chair Seattle Sen. Reuven Carlyle and everyone else on the committee you support House Bill 1336.