On Monday, April 20, 1908, the front page of the Coeur d'Alene Evening Press heralded the arrival of a celebrity.

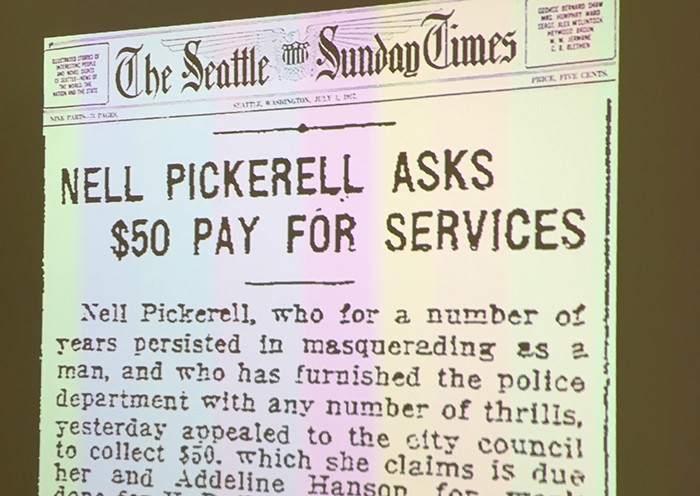

"Nell Pickrell, notorious throughout the west by reason of her escapades while masquerading as a man, together with two companions arrived in the city from Spokane today," the report went.

Then, "Shortly after her arrival in the city her identity became known to Chief of Police McGovern, who ordered her to leave town, and she departed with her companions on the afternoon boat for St. Joe."

Nell went by Harry. Harry's story is real, demonstrated in 45 newspaper clippings collected and exhibited as a projected slide show by the contemporary artist Chris E. Vargas, himself a trans man who lives in Bellingham with his cis gay male partner.

Who is trans? What is trans? Harry wasn't called "trans." The media dubbed him a "bad man" and "itself," so to find him in the archive, you have to chase down details and codes. Vargas gives him a place: Harry is trans. Vargas is trans. They face across time. I see you.

The place that Vargas gives Harry is contained in a museum within a museum in Seattle right now.

The outer museum is the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington, but it could be any established institution. Near its entrance is a doorway to another, inner place. Admission, unlike to other areas of the Henry, is free. Vinyl lettering at the doorway says MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas present: Trans Hirstory in 99 Objects.

MOTHA is the Museum of Trans Hirstory & Art, which doesn't actually have walls but rather exists as a series of events and ideas organized by Vargas since 2013. I know of no established trans museum that does have walls. In the early 20th century, the famed Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin (portrayed in the second season of the TV show Transparent) recognized and documented trans identities as central to gayness, but was raided and shut down by the Nazis. In 2004, a drag queen in Lima, Peru, founded the ongoing El Museo Travesti del Peru, which like MOTHA is ephemeral. (The "hir" in MOTHA's "Trans Hirstory" is a nonbinary pronoun.)

Creating MOTHA was a riff by Vargas on the British Museum's A History of the World in 100 Objects and the American riposte The Smithsonian's History of America in 101 Objects. After Vargas used huge novelty scissors to cut a ceremonial red ribbon on MOTHA, he began to imagine a series of shows—Trans Hirstory in 99 Objects—that would gather material for a permanent MOTHA collection.

"The process of building a museum and acquiring collections is a big undertaking requiring resources trans people are still struggling to access, along with health care, housing, and employment," Vargas wrote. "Leading the list, of course, is a top-secret, temperature-controlled bunker 7.5 miles underground in which to store MOTHA's growing and highly coveted collections."

Vargas is an artist with a sense of humor and proportion. He talks up his museum, and then shrinks it down to size. Yet he is earnest. MOTHA represents work. Research. Time spent in libraries, online, talking to people, reading books, finding contemporary artists. 99 Objects is a mix of artifacts and art.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, Vargas found for MOTHA an expansive past, present, and future. Trans is not new, not invisible, not infertile.

Trans is Storme Webber's poetic description of Seattle butch, as something neither male nor female but its own destination, as timeless as the waters bordering downtown. Trans is micha cárdenas, a Latina trans woman who writes of returning to testosterone in order to bank her sperm to impregnate a partner, of being pregnant herself with life, with "swimmers!" despite the advice of doctors and an entire society that considers pregnancy strictly in uterine terms.

Harry, Webber, and cárdenas link arms across time with the performers at the Garden of Allah, a post-1945 club in downtown Seattle where men performed as women and vice versa. In one photograph, a dainty, picturesque trans woman poses between two happy soldiers in uniform.

About the photos, someone asked Vargas, "Did they live as female or just perform as female in the club?"

Maybe the real meaning of the question was, were they really trans? How does a real transgender person act? Those are the natural questions of the creators of a museum collection. What do you put in and what do you leave out? A museum is like law enforcement. It decides and presents what something is allowed to mean. It offers community, identification, comfort, and safety. It is also monstrous if you are left out. Considering that the trans community has no museum, a museum for the trans community is a contested project right from the start. Vargas created MOTHA out of a real emotional need for belonging, yet is very clear that "I don't want to be a gatekeeper." Gatekeepers enforce gender, haul Harry to jail.

In the gallery at the Henry, the air is colored with the overhead strains of Billy Tipton's piano. A record player sits on a pedestal next to the LP of the 1957 album Billy Tipton Plays Hi-Fi on Piano. A didactic label explains that Tipton passed as a man for 50 years, even shocking his wife upon his death.

This interpretation of Tipton's story is not the only one. It's just the most popular, the one that has most fascinated media and audiences since Tipton's death. But other versions feel truer: that plenty of women in Tipton's life knew, including his wife. Or maybe there is even something less easy there, like knowing but pretending not to know, making way for all the Boy Scouts and PTA meetings the Tiptons were known to attend in their suburban lives when he wasn't playing music. What's true about Tipton is that he was a trans man. But a conventional audience might easily prefer that the "man" part, and all those scouting trips, were fraudulent. Vargas's label defaults to the popular story and uses the power of the museum to reproduce it.

No mere pride parade, 99 Objects is a serious, and pointedly small, display (there are far fewer than 99 objects, you may notice) of art and resources. There's a video interview with the founder of Seattle's Ingersoll Gender Center mounted with the actual old mirror from the center, which countless trans people have used to picture themselves anew.

Other surfaces are essentially voids. Lorenzo Triburgo photographs fabrics so dark they could be hiding anything, paired with aerial views of unpopulated areas in the Northwest where someone might hide out like a small forest surrounded by farmland. Someone might hide, or be hidden away from society and surveilled—these kinds of landscapes are where private prisons are built. The images are paired with audio from conversations the artist had with inmates he's corresponded with as pen pals.

The mere fact of a MOTHA hosted by an existing mainstream institution like the Henry is a sign of the progress in American culture at large. This is the year when the president of the United States mandated gender-neutral bathrooms at public schools. The question is always and only, how far does it go? Jono Vaughan, an artist in Seattle, makes lively patterned dresses in honor of trans women who have been killed. Vaughan designs the fabrics based on Google Earth images of the sites of their murders. The dresses are then worn and performed by living artists, reanimated (a performance at the Henry is happening November 13). Vaughan says the title of the series, Project 42, refers to the average life span for a trans woman today.

I pin much hope on the November performance of Vaughan's dress—and I suspect this duality is its point—because looking at the dress in the gallery, lifeless and unperformed however lively its colorful fabric, is a desperate and devastating experience, as nightmarish as an image of a lynching.

Performance rather than fixity is central to MOTHA, the hopelessness of pinning down an identity translated into a kind of hope, possibility. MOTHA pushes against the limitations of its form, which is a canon. Can a museum wear drag? Or will it be criticized for having it both ways? It seems yes and probably yes. Which is very trans of it. ![]()