This is a history of a hostile building, and it ends in the dark. A man in a small room is moaning. His door is open. His light is out. The door that faces his door is also open, the walls inside that room swimming in blue light, the guy on the bed riveted to the TV or asleep with his eyes open. Down the hall, in a bigger room, a black guy pushes a dildo into a white guy's spread-open butt, holds it at crotch level and pretend-fucks with it, loses interest in what he's doing, removes the dildo, hops off the bed, and walks out. In a "deluxe" room, a guy is luxuriating in the comforts of dungeon amenities. He has a sling hanging from the ceiling above his bed but apparently he doesn't have the energy to climb into it. It supports one raised leg. His body is doughy. His face is eager. He's fingering himself.

He hollers at me, "Hey! What are you doing?"

"Just looking around. You?"

"Just hanging out!"

This is a year ago, a Thursday night, minutes before midnight, hours before the 9:00 a.m. closing time, weeks in advance of the building's expected demolition. The demolition has been moved back repeatedly. Plans for this site's redevelopment keep stalling. It's a wonder the building hasn't died of its own volition. Until Initiative 901 outlawed smoking indoors a few months ago, there was an ashtray in every room—and there are no windows whatsoever. The members of Club Z spend their time standing in the dark, masturbating, having sex with one another, fisting one another, walking the hallways, walking up and down stairs, looking through holes in plywood, staring at TVs, staring at nothing. Many appear to have, in one way or another, checked out. I visited Club Z more than once in the course of working on this story, and I've seen strung-out men, and out-of-their-heads-desperate-looking men, and men who are way too attractive to be doing what they're doing to the guys they're doing it to but carry on with a kind of generous boredom, and a number of naked men of all ages and sizes fast asleep, blacked out, dreaming.

The building is at 1117 Pike Street, between Boren and Melrose Avenues, one of the most trafficked blocks in the city, but you've likely never noticed it. History has barely noticed it. It's a void. My obsession with it is personal. It haunts me. If all goes to plan, it will be destroyed this year, the year it turns 100, which feels right. It is a building that has destroyed people. This is a story of many kinds of death, and of misery's association with a building whose past is a tangled mess of war, disease, drugs, wrecked loves, and real estate.

The building is the colors of a pigeon. An asset manager for an investment real-estate company who lives one block east of it describes it as one of the "missing teeth" in a developing neighborhood. His wife says, "It's an eyesore." Since its construction in 1906, the building has had many commercial incarnations, with storefronts, but now every window on its face is boarded over.

Its horribleness is sort of captivating. One afternoon, employees of the Utrecht Art Supply store across the street were staring out at it, in full agreement.

"It looks like shit."

"Oh yeah, absolutely. Just a coat of paint would help."

One said something about the building's essence being "behind doors," and a third guy ventured, "I think actually the exterior makes you think it's worse than it is."

The building is something Jill Janow wonders about—she is the neighborhood's city liaison and knows everything about the buildings in the area—because, as she puts it, "They didn't make friends with anybody. I don't know anything at all."

It's possible Janow and the art-supply store guys don't know anything about Club Z because none of them are gay men. Among gay men, Club Z is mythic. It is known as a locus for extreme sex, drugs, and rough stuff, attracting "the leather/daddy/sleaze types," writes a user on www.squirt.org, an anonymous-sex website. Club Z attracts clientele like the "total bottom" looking "to get fucked over and over" who often posts on www.cruisingforsex.com about Monday night "fuck fests" at Club Z, giving out his room number and an enchanting, "Come on down, it's gonna get sloppy."

Club Z had developed its reputation for raunch and drugs as early as 1985. That year in Seattle Gay News, writer Joel Vincent described Club Z as "much more 'hardcore'" than other bathhouses in town and described an interaction with an employee who turned out to be tripping on acid. "I'm not certain if the AIDS problem has affected [Club Z] members who seem to be caught in a time warp, putting forth their strong 'macho' type image, cavorting like 'trash' in the unlit 'maze'/orgy area," Vincent wrote.

Almost a year ago, in advance of the demolition expected last summer, Seattle Gay News published an article by Don Paulson called "Farewell, Old Friend...: Club Z Slated for Demolition This Summer," which described the place in similar terms. This was the first paragraph:

Club Z (AKA Zodiac Social Club) is closing its doors after 35 years. If only those walls could talk! A sauna has replaced the steam room but nothing can replace the raw energy of the male sex, from vanilla to chocolate, that happened within its walls. Society has taken away everything from Gays except sex, which is the driving force on this planet. Is it any wonder that some Gays have developed into legendary proportions? It's not that Gays are so 'bad,' it's that Gays are so much fun. But such indulgence does not take away from their capacity to be sensible or to love, even through a glory hole or properly secured in a leather sling, thank you, Sir!

The "AIDS problem"—there is an object lesson in understatement. I wonder if it's coincidence that the rise of the "AIDS problem" coincided with increasingly tantalizing advertisements for Club Z. The downtown library has a full archive of Seattle Gay News, and in the first week of 1982, the front page carried the headline "Cause of 'Gay Cancer' Unclear." ("To date, 23 men from across the country have been described as having this new syndrome, and two-thirds of them have died.") Inside that issue was a small ad for Club Z—an innocuous drawing of guys in a locker room and the blasé tagline: "Join your friends for lunch at the Zodiac." (Lunch?) Three years later, when the New York Times was reporting that 6,481 people in the U.S. had died from AIDS and 13,332 people were living with death sentences, Club Z's ads had ballooned to full pages, with photographs of men on beaches, in wrestling rings, lathered in soap, beside swimming pools, glowing in the sexy bliss of life itself.

One ad that kicked up controversy was a 17-inch-tall photo, published June 14, 1985, of a stud sitting naked on a kitchen stove, drinking milk. The text reads, "Nothing satisfies like..." and then one's eye falls on "milk," printed across the carton. A Seattle Gay News reader wrote in about his "problem" with the "really, truly offensive" ads for Club Z that the newspaper was publishing, calling them "trash." Another letter to the editor called Club Z's ads "completely out of order."

The management at Club Z responded on the Seattle Gay News letters page with a bristling letter of their own. They wrote that it was "ludicrous to retreat into a medieval state of shame, given the advances we've made in exercising the right of our expression as human beings" and that "[while] we recognize and respect the right to dissent in the presentation of one's point of view, the Zodiac will not be governed by nor submit to the narrow-minded repressive venom dripping from the lips of those who emulate Christian fundamentalists or any other societal bigot who perpetrates prejudice, injustice, or Neanderthal ideology" and that "it seems pitiful and abhorrent that the knives of some gay men are always sharpest when being plunged into the backs of their brothers" and—it's a hell of a letter—that concerned Seattle Gay News readers objecting to the club's ads "have unwittingly done the work of our true enemies, and... have played the role of Judas with each finger they've pointed against the Zodiac and the SGN..."

Judas is a bold leap there—if you follow the analogy, the bathhouse is Jesus—invoking themes of betrayal, sexual jealousy, murder. But throughout its history Club Z has brought the specter of sex very close to the specter of death. Another ad in 1985 depicted a naked jock, his back toward you, with the words, "You'd better sit down for this." That's a butt-sex joke. It's also what your doctor says to you when he has really bad news—and 1985 was a big year for bad news. Another ad that year asked: "Where Have All the Real Men Gone?"

Hmm. The hereafter?

Truth is, no one knows how many fewer men would have disappeared if the club had softened its ads or closed its doors. The role bathhouses played in the spread of HIV in the early '80s—and the role they play today—is unknown. "Do unsafe behaviors take place there? Undoubtedly, yes," says Dr. Hunter Handsfield, a professor of medicine at the UW Center for AIDS and STDs. "If the bathhouse didn't exist, would the behaviors change quantitatively or qualitatively? People behave the way they behave through an extraordinarily complex set of determinates that are not fully understood when it comes to sex... As far as we know, the environment isn't all that important."

The debate currently animating the gay community is not about bathhouses—though they were a subject of debate in the '80s, and some were shut down—but about how to address men who have unprotected, drug-fueled sex with strangers, often in places like Club Z. The clinical psychologist Walt Odets told the New York Times not long ago that proposed interventions to force HIV-positive gay men to communicate about their health status to others "smacked of a witch hunt." On the other side of the debate, ACT-UP founder Larry Kramer, a proponent of such interventions, declaimed in a recent speech, "You are still murdering each other."

Bathhouses are unregulated and unstudied, which is why it's unknown how much "murdering" goes on inside them. As for Club Z, short of entering yourself, it is virtually impossible to learn anything about it. Friends of friends who frequent the place wouldn't talk to me. Carlos Adams, who runs the club, did not respond to repeated attempts to contact him. Countless phone calls to the owner of the building—who is going to replace it with a mixed-use structure of condos and ground-level retail—went unreturned. For more than two years, the architect seeing the project through, Kenn Rupard—who is listed as the contact for the project on permits and public documents—has never answered or returned any of my calls.

How else can you learn about a building if no one associated with it will talk to you? The city has some information about buildings, and the Seattle Municipal Archives website has a search function that yields a lot of historic photos of Pike Street, but not, it turns out, of this address. I visited the Seattle Department of Planning and Design, where an employee let me look through a stack of topographical maps of localized areas of the city. I looked through them all, they weren't in any particular order, and none of them charted the block in question—not that a topographical map would have been helpful. I just wanted something. The employee advised me to visit the records vault in the city's Engineering Resource Center because they had "literally millions of photos," although, as I learned when I got there, the photos in the records vault are incredibly disorganized and aerial. After some effort, and with some assistance, I located the building. I mean, I located an image of the square roof of the building.

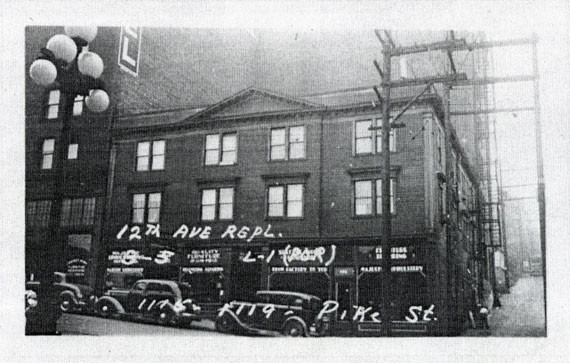

Here's the problem: No one considers 1117 Pike Street "historic." The City of Seattle Historic Preservation Program has photos of the brick hotel that borders 1117 Pike Street, but they have no photos of 1117 Pike Street. Eventually I did manage to find two good street-level photos—taken in 1937 and 1949—in Bellevue, in the state archives. I found them by calling the Puget Sound Regional Branch of the state archives, pressing buttons until I got a human, explaining my project, and providing the building's tax parcel number. Within five minutes the employee called back to "double check" that I had the right tax parcel number. "It's not a very impressive-looking building," she explained.

"That's it," I said.

Lindy West, a Stranger intern who became my research assistant that instant because she has a car, drove me to Bellevue Community College. That was where we would make our big historical discoveries, with the help of a no-nonsense woman at the front desk named Philippa Stairs. "Phil," she insisted. I sacrificed my backpack, my bottle of water, my pens, and then Phil let us into a room to see a card of information on the building comprising 1115, 1117, and 1119 Pike Street. (Now that Club Z occupies the whole building, the address has been consolidated to 1117 Pike Street.) Taped to the card of information were the 1937 and 1949 photos. In both photos, the streetlamps are cluster lights. In 1949, an out-of-focus man is walking by.

"It's not much of a building, which could be a very good thing," Phil said in an if-you-catch-my-drift way.

I didn't catch her drift.

"If it's a bathhouse and people don't want you to know it's a bathhouse," she said.

With a magnifying glass, West and I established that the building's storefront was "Majestic Upholstery Co." in 1937 and "Sweeney-Berwanger Co." in 1949. Actually, the "w" in Berwanger was a guess. I mentioned this to Phil, who told me I could check the name of the business by looking up the address in Polk's Seattle City Directory 1938. The Polk's directories, starting in 1910, were published yearly until the mid-'90s. In 1938, the volume's publishers began including a reverse directory, meaning that, instead of looking up a business and finding its address, as with a phone book, you could look up an address and find the business at that location. With a set of Polk's directories, you can reconstruct the commercial history—in a sense the cultural history—of any area of the city. We were thrilled to find names of automotive businesses, groceries, and upholsterers, and set about charting the yearly progress, from 1938 onward, of 1115, 1117, and 1119 Pike Street, addresses that no one has ever had any reason to remember.

The Polk's directories are not online—"There's a lot of things you can't find online," Phil intoned—and the earliest editions don't have reverse directories. (They also fall apart as you turn their pages.) The reverse directory in the 1938 edition indicates that in 1938 "Majestic Upholstering Co." occupied 1119 Pike Street, the "Roland Apartment Hotel lodgings" occupied 1117 Pike Street, and the 1115 Pike Street address was vacant. Since the reverse directory wasn't published any earlier than 1938, it's impossible to look up those addresses in earlier editions; however, you can use the earlier editions to look up businesses that you know existed eventually, to see when they first appear. "Majestic Furniture Upholstering Mfg. Co." first appears in 1933. "Roland Apartments" first appears in 1928.

Here's another wonder of the Polk's directories: Early on, the directories included the names, in parentheses, of the manager of every business listed. In 1930, the manager of the "Roland Hotel" is G. Nakahara. By 1938, the listing has changed to the more complete "Roland Apartment Hotel lodgings" and the manager is Yoshinobu Hasegawa.

Hasegawa is the manager in 1939, 1940, 1941, and 1942.

And then, he disappears.

Hasegawa is a Japanese name. If you were Japanese and living in Seattle, 1942 wasn't your year. That spring, the Wartime Civil Control Administration nailed thousands of posters with instructions to all persons of japanese ancestry to telephone poles around town. On a hunch that Hasegawa's 1942 disappearance from the Polk's directories was no coincidence, I called the Quick Information Center at the Seattle Public Library. I gave them what I had: a name (Hasegawa) and a place of employment (the Roland Apartment Hotel). The next day, a Saturday, I got a call from Jeanette Voiland, Senior Librarian in History, Travel & Maps, who told me that a search for Yoshinobu Hasegawa in a central database of interned Japanese Americans maintained by the National Archives and Records Administration came up empty.

The day after that I met Voiland and she showed me the database. She was right. A search for "Yoshinobu Hasegawa" turned up no records, although a search for "Hasegawa" alone turned up hundreds. Each name had alphanumeric codes next to it, each code corresponding to information about each internee: race, religion, birthplace, birth year, year of arrival in the U.S., last permanent address, etc. I searched for "Hasegawa" only among individuals whose last permanent address was in Seattle. That got 27 results. The ninth-from-the-last name was "Hasegawa, Yoshinob."

According to the codes, "Yoshinob Hasegawa"—his name apparently didn't fit—had been living in Seattle and had an occupation that fell into the category "Hotel and Restaurant Managers." This was clearly the guy. I learned from the other codes that he was born in Japan in 1887 and arrived in the U.S. in 1910. He was widowed. He had a high-school education, knew English, and had gone back to visit Japan twice since moving to America. The records showed that, after being rounded up, he was first taken to fairgrounds in Puyallup, where thousands were forced to live in temporary housing built in parking lots and horse stalls, and then he was sent to Minidoka, an internment camp in Idaho.

At Minidoka, Hasegawa lived in Block One, Barrack 7D, along with Hiroshi, Yukio, Naoko, and Yukinao Hasegawa, which I know because I subsequently found his name in The Minidoka Interlude, a book published by residents of Minidoka Relocation Center. (There are several groups of Hasegawas in the book, but only one with anyone named Yoshinobu.) Nearly 10,000 Japanese men, women, and children were imprisoned at Minidoka, "one of 10 concentration camps built on the wastelands of America in 1942," writes Jack Yamaguchi in This Was Minidoka. "In most places the sandy ground never hardened and was a never-ending source of dust and grime in the barracks. The wind often swept down upon the camp, raising suffocating clouds of dust which poured through the loose-fitting windows and doors." There were armed guards in towers, there was barbed wire, and there was a shortage of medical staff. Death, Yamaguchi writes, was "ever present."

One way to get through the barbed wire was to volunteer for service in the war. Hasegawa, in his early 50s, was too old to qualify, which maybe saved his life. In the end, writes Yamaguchi, Minidoka had "the largest casualty list of any of the 10 relocation camps." Among those casualties, according to a few obituaries reproduced in This Was Minidoka, were two young Japanese men who had previously attended Broadway High School. Broadway High School was once located where Seattle Central Community College is now, a three-minute walk from Club Z.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, in Japan, in 1944, Allied forces were preparing to bomb Okinawa. An 11-year-old Chinese girl living in Taiwan—her first language was Japanese because Taiwan had been under Japanese occupation her entire life—remembers finding leaflets dropped from U.S. warplanes warning Taiwanese civilians that the siege on Okinawa was coming. And she thought: "How wonderful these people are to warn people! That's the first impression I got of American people—they're so nice and generous."

As a young woman, she longed to move to the U.S. "At the time, for me, that was like going to the moon." When she was old enough to leave home, in 1950, she unrolled a map of the U.S. and chose to leave for Kansas, because she wanted to be in the middle of everything. Then she visited her brother in Seattle. "I really liked Seattle a lot better than Kansas." She transferred to Seattle University in 1954, and soon after met her future husband in a nightclub in what was then called Chinatown. "It was kind of a pickup place," she admitted to me. They were so embarrassed they didn't tell their kids where they'd met. They've been married since 1957.

Her name is Joyce Marleau. Thirty years ago, she became interested in investing in real estate. In the spring of 1978, she read an ad for a building that seemed within her means and talked to a realtor, who discouraged her. "He said, 'It's really hard to get in to look at this building.'" Six months later she saw the same ad and thought, "I've got to see this building, I don't know why."

Club Z, known at the time as the Zodiac Social Club, had been in business in the building for about a year. When Marleau arrived with her lawyer and realtor to see the building, the tenants wouldn't let them in. Women were not—and are still not, and have never been—allowed in the club. "So we had to make another appointment," she said. "I don't know what they did—maybe clean some places."

When she finally did see inside the building, she said, "It was horrible... I didn't realize gay people do that kind of thing. It was awful... It was horrible. I nearly vomited when I heard what they were doing, and this was before the AIDS." She bought the building because "it was in a good location."

This diminutive woman in her early 70s has owned the building housing the most hardcore bathhouse in the city ever since. I met her once, briefly, at a design-review meeting at City Hall two years ago. For months I tried to get back in touch with her. She wouldn't return my calls. Then last spring, after I'd left dozens of messages, I called again—I kept calling on the off chance that she might pick up. She picked up. She told me she hadn't returned my calls because she wants to keep the redevelopment project "low-key." She told me that the place was originally built in the 1920s. I told her it was actually built in 1906. "Wow, 100 years old," she said. "It's really bad... the way the outside looks. The surrounding neighborhood is remodeled and, our building, we never did anything."

I mentioned the boarded-up windows and she said, "Yeah, so tacky!" Then I asked her if the management of Club Z kept changing in the 1980s—something I noticed in the Polk's directory—because the managers kept dying, and she said, "Mmm-hmm!"

Marc D. Sauer is listed as manager of the "Zodiac Social Club" in the Polk's directory of 1978—the first year the club appears. In 1980, James Barrett is listed as manager, and in 1983 James Barnett (who is probably the same person, although maybe not) is listed. In 1985 it's Ron Wilson, in 1989 it's Brad Gruman, and in 1993 the Polk's directories cease publication. Similar resources published more recently don't list managers. According to the Social Security Death Index database for Washington State, a Marc D. Sauer, age 42, died in Seattle on August 9, 1989. An obituary appeared in Seattle Gay News two weeks later citing "respiratory failure and complications from a long battle with HIV" as the cause of death. Nine James Barnetts in Washington State died between 1983 and 1994, two of them, both relatively young, in King County. There are lots of Ronald Wilsons, including Ronald L. Wilson, age 48, in Lynwood in 1993; Ronald E. Wilson, age 59, in Tacoma in 1993; and Ronald D. Wilson, age 66, in Seattle in 1995. Several of these deaths received notices in the daily newspapers, but just standard death notices, which only say, So-and-so died. That's where the information ends.

Yoshinobu Hasegawa, the Roland Hotel Apartments manager who was sent to Minidoka, died in a nursing home in 1965 and got a somewhat detailed obituary in the Seattle Times. But he is also somewhat of a ghost to history. You now know all that I know. I have an acquaintance whose last name is Hasegawa, but he isn't, it turns out, related. Hasegawa's obituary mentions membership in the Japanese Apartment and Hotel Owners' Association, but that organization no longer exists. There is a picture in The Minidoka Interlude of the 130-plus residents of Block One, but it is impossible to know which one of them is Hasegawa, and he is in none of the many smaller group pictures captioned with last names throughout that book. According to Hasegawa's obituary, his body was cremated at Butterworth Mortuary, two blocks from where Club Z stands, in what is now a bar with ghost-white furniture called Chapel.

Since half the general population isn't allowed inside Club Z—including the neighborhood's liaison to the city and the woman who owns the walls in which the glory holes are carved—here's some information about how the club works and what you generally find there. Membership is required. According to a figure published last summer in Seattle Gay News, they have about 4,000 members. Memberships last one year, for $17, or six months, for $10 (although for a while last spring Club Z was offering month-to-month memberships in anticipation of the building's demolition). Paying for a membership gets you a membership card. Once you've shown your membership card and paid for either a locker ($9–$11) or a standard room ($15–$17) or a deluxe room ($28–$35)—prices vary depending on the night of the week—you are buzzed in through a heavy door and issued a towel, a key for your room or locker, and a condom.

The locker room is on the first floor, along with a shower and a sauna—both rarely used. On the second floor are dozens of small rooms, as well as a large room where several monitors play videos and men stroke themselves and smoke. On the third floor are still more rooms and a "maze" that consists of partitions set at angles from one another—many of them with holes at crotch level—in almost total darkness. In certain corners of the maze it's possible to be standing next to someone who's loudly getting fucked and not be able to see them. The rest of the building is staircases and hallways full of loiterers. Since doors are usually closed, you can't see into any of the smaller rooms, except those that have glory holes.

Sometimes doors are left open. Occasionally you walk by a room and see someone on their stomach, bare ass facing you, waiting. Or you see someone sitting up in bed, masturbating, trying to be inviting. The idea of the club is that anything is possible, that pleasure and adventure reign, that a sexual energy prevails that's not allowed expression outside the club's walls—but the truth is that a lot of these men look extremely bored. At one point I walked into a large room where a handsome guy in jeans and a baseball cap was flipping channels. A hardcore dildo scene... a pool scene... a guy getting comed on... an ass being eaten... a group scene in which some of the guys were tied up. He settled on the group scene. He watched. A few people walked by. He looked around the room. He watched some more. He looked at me. I was being standoffish. At last he said, "I want a pizza."

On a chalkboard in the bathroom down the hall, several club members had written messages:

340 FIST/FUCK PARTY

213 BB TOP

232 Piss in my mouth

233 HOT NO TEETH BLOWJOB

370 SLING MY ASS!

I was interested in the party in 340 because I wanted to see a group scene. Group scenes at Club Z seem to be exclusionary—a few guys meet, find a room, and close the door. It's rare to find groups of people having sex in any of the common areas, which is odd, because you expect the patrons of a bathhouse to be voyeuristic and confident and driven by values that run in opposition to everyday conduct, and so would be swinging naked from the rafters or whatever, but in fact most people here have sex in shabby approximations of privacy. The walls of the rooms don't always go up to the ceiling, so you hear things, but a certain level of privacy is important to most, and it's necessary if you're going to do drugs. According to posted rules, drug use is prohibited.

The door to room 340 was open, a red bandanna tied to the door handle. Inside, a huge man with studded genitals was suspended from the ceiling on his back. Another man stood between his legs, putting on gloves. There was no one else in the room. They introduced themselves. The guy in the sling was Carl. The guy in the gloves was BJ. They were not attractive.

BJ scooped some white lubricant out of a tub and began sliding his hand into Carl, whose expression was casual. A large diaper pad was spread out on the bed below Carl. On the television screen, a man was sinking a dildo into another man. BJ was plunging his hand in and out of Carl, slowly, not being too aggressive, not punching, warming it up. They did this for a minute and then BJ looked down at his hand and said, "Uh oh. Brown." He pulled his hand out. The white lubricant was tan. Carl sighed big and literally said, "It's been one of those days," and got out of the sling and went off to the bathroom, and BJ said something about not being afraid to get shit on his hands.

In the locker room, as I was leaving—I had come to see if I could get turned on; I couldn't—a sexy guy who told me he was visiting from Amsterdam asked me if I had had fun. I admitted that I'd found it boring.

"It is boring," he agreed.

My first time inside Club Z, a boyfriend, whom I'll call F., took me. Early on in our relationship he told me he had been "experimenting" with some things, which turned out to mean that he had been using crystal meth and, while on meth, getting fisted. This is more common than you might expect among men who use crystal meth. He hadn't done it much and he talked about it nervously. I was open-minded and wanted to know everything. He said he had first used the drug with a boyfriend and, after that ended, once or twice with people he met at Club Z.

Because I loved him, I wanted to see the place where he had done this insane thing. I remember thinking that it cost a lot of money to get in, more than $40 for both of us, and that I didn't want to touch anyone. I remember some grotesquely fat men in towels. (I say that as a person who was once fat.) I remember standard-issue ugly men, and lots of average men, and older men I wasn't attracted to, and muscled men who looked blasted, and a few young guys I assumed were HIV-positive—in other words, the only person I wanted to have sex with was the person I came with. It was my idea to leave the door open, to be wild, but within minutes the room filled with people who wanted to touch us. I wasn't into it, and F. kept muttering how disgusting the place was, so minutes into the adventure we put on our clothes and left.

Turns out, F. liked the place better when I wasn't with him. While we were a couple he went to Club Z four or five times, always without telling me, always when I was gone for a night or a weekend. I'd return home to a shaky, babbling version of my boyfriend. He went when he was alone and bored. And he was always bored. Work bored him, people bored him, the city bored him; he was a bored person. I guess he was bored except when on meth.

On one level, it made him happy.

I wanted him to be happy.

Crystal meth is not a sexual stimulant. It's a central-nervous-system stimulant. It was developed by a Japanese scientist in 1919 and used by U.S. and British pilots in World War II to keep them alert, and, in larger doses, by Japanese kamikaze pilots. "It makes you feel incredibly good, like you're some kind of god," says D. L. Scott, clinical coordinator for Project NEON at Seattle Counseling Service, whose programs for gay men on meth have grown exponentially in recent years. Eighty-five percent of the users who come into the clinic use the drug to enhance their sex lives. "It's a big social drug in that there are a lot of big group sex scenes. [Users] say it doesn't matter who the person [they're having sex with] is as long as they have a dick. There are group scenes where you have 10, 20, or more people engaged in sexual encounters."

And it's hugely addictive.

"It's bad news," Scott says. "Real bad news."

Within 15 to 30 seconds of it being ingested into the body, methamphetamine floods the bloodstream with dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, tons of it, raising blood pressure and body temperature, elevating sensory perception, obliterating inhibitions, and erasing pain. It makes getting someone's fist into you, a psychotic idea to most people, possible. "Some of my patients talk about how they feel on crystal meth as being akin to being robots programmed with the sole purpose of doing more crystal and having more sex," Dr. Steven Lee, a psychiatrist, told the New York Times, which has published lots of reporting about the rises in meth use and HIV transmission among gay people.

A "dangerous nexus has formed between the nation's two big epidemics: AIDS and methamphetamine abuse," writes David J. Jefferson in Newsweek, citing a 2004 study among gay men in Los Angeles County. Thirteen percent of the men in the study had used meth in the previous 12 months and "those respondents were twice as likely to report having had unprotected sex, and four times as likely to report being HIV-positive." Jefferson's article began with an anecdote about three dozen men—many of them "sweaty, dehydrated, and wired on meth," and HIV-positive—having unprotected sex in a hotel room in New York City. One of the men said, "It's completely suicidal, the crystal and the 'barebacking.' But there's something liberating and hot about it, too."

Hunter Handsfield, the UW professor of medicine, told me, "If you're a meth-using [HIV-negative] gay man who comes into the STD health clinic at Harborview, and then you show up again one year later, there is a 25 percent chance you will have become HIV-positive." There are very few populations in industrialized countries with those rates; you have to look among "subsets of commercial sex workers in Africa," he said, to find such statistics. When Handsfield was the director of Public Health, Seattle and King County's STD prevention program, he never urged the closure of Seattle's bathhouses because numbers have always shown that HIV spreads at the same rate in cities that have bathhouses as in cities that don't. He concedes that if people can find meth in bathhouses, that makes them more dangerous from a public-health perspective, but he added, "If you cracked down on that—not using 'crack' for any particular reason—would meth use change? Or just happen somewhere else? I don't know."

I have been offered meth several times in the last year, always unsolicited, both online and at Club Z while working on this story, but I've always turned it down. I am terrorized by what it did to my ex-boyfriend, who entered recovery toward the end of our relationship.

I was also offered a lot of sex at Club Z. When two guys—one of them handsome and normal, a guy I would go on a date with—offered to have a three-way, I declined. I have a mild phobia of strangers' gooey privates. I'm afraid of STDs. But I let these two guys have sex in my room because neither of them had his own room and they were willing to let me watch. The one I liked, Handsome and Normal, got on his back on the bed, and the other one held Handsome and Normal's legs in the air, and they had sex for a while in a variety of positions on the bed and on the floor without condoms. It stunned me how little they said, how absent language was. I assumed they were both HIV-positive because they both seemed to assume that about each other. In any case neither brought it up. I began thinking about—not in a patriotic way—the idea of freedom, namely the freedom to do to your body what you want. Seems like a necessary freedom. I thought about my friends who are HIV-positive, and about what it would be like to be gay and HIV-positive in this country right now, in other words to be in the margins of a margin, and how that might change your feelings about "community." It occurred to me that some people are more comfortable with the idea of living with HIV than others are, and that people smoke even though it will kill them, and that we all die somehow, and that the unlawfulness of suicide has always seemed unjust to me.

My problem with meth is that it removes reality and an awareness of consequence from experience—in other words, it makes you less free. I could never understand why my ex-boyfriend liked getting fisted, but I think it was related to a desire for intensity. The problem with that is: What's next? Are you going to stop here at the fisting level? It made me panicked for him, and sad, which probably made me love him more. I won't tell you any details of his life, because it's proper to protect his identity, but he is the kind of guy who wanted more than anything to be extraordinary.

When I watched BJ and Carl in that room, it made me wonder which rooms F. had been in and how many other people had watched him. During our relationship I used to wonder those things a lot—how many men at Club Z were involved, who they were, whether the door had been open. These questions terrorized me. So did the place, the menacing building itself. I forgave and forgave and forgave F., and then, the fourth or fifth time he went, because somehow he couldn't stay away, and then lied about it, I couldn't forgive him anymore. In that way, this building killed us.

Joyce Marleau is hoping that the ground floor in her new building will be a deli. Janow, the neighborhood liaison to the city, loves the way the Kenn Rupard–designed redevelopment will look, adding, "It's going to be a major attraction in the neighborhood." It's also going to greatly improve the value of the property. The real-estate businessman who lives a block east of Club Z speculated that the land alone is worth $750,000–$850,000, and that if the new building becomes condos the whole thing will be worth "upwards of seven million dollars."

At one Design Review Board public meeting I went to at City Hall two years ago, four people in glasses sat along a table and talked about plans for the building that's going to replace Club Z. They talked about parking, fenestration, terracing, signage, overhead weather protection, sidewalk trees, the neighboring hotel, the pedestrian zone, views that would give "a sense of openness," and shadows. One of the men at the table asked for information about sunlight at different times of the year.

"Shadow study," someone said. A shadow study would show "details and layers and shadow and context."

There were nine members of the public present, but they only had comments about future windows and future trim. No one, throughout the meeting, said a thing about the current building. Maybe its details, layers, shadows, and context are too much to bear. I found the silence kind of poetic.

I stopped last week to ask the person at the front desk when the building is expected to be torn down. "Not until the end of the summer," he said. Men who post on the web about anonymous sex have been delighting in the gift of more time, of extended life. They haven't been silent at all. Someone wrote on www.squirt.org:

I was there last night... and there was a sign saying the lease had been extended. Had a great time while I was there. Was piston fucked by this dominant guy who worked me in every position possible with him being on top. Then, this Hispanic guy slowly teased me with his cock, edging himself closer and closer until he couldn't hold back any more. Then this hot daddy stud with a really thick cock pounded me doggie style. He didn't last too long before he unloaded—boy did he bellow when he shot! This young black guy with a rock-hard cock finished off my evening there. The only thing he said to me was "thanks" as he left my room. Gives you an idea of the diversity of the guys that play there. And this was on a Wednesday night! It's going to be too bad when this place is gone.