This is a story about the summer I got drugged in North Africa. Every time I tell it, I hate it a little more—for reasons that, I hope, will become clear. In fact, this may be the last time I tell it.

One summer afternoon several years ago, when the heat was so heavy, you could feel its weight on your shoulders, I was sitting outside at a table in a medium-sized town in the Rif Mountains drinking a cloudy tumbler of atay, a sweet green tea made with spearmint leaves that is popular throughout the Maghreb.

I don't remember exactly what I was doing at the moment, but likely candidates include writing bad poetry (just to prove I'm being honest with you, here's an embarrassing stanza I recently found in my notebooks from the day in question: "Light quietly escapes from the mountains / 3 peaks torn by hooves, water, and god / bright white—& yellow—slides from the surface / flood without depth") or nursing a juvenile fantasy about meeting a smart and adventurous young lady one starlit night when it was too hot to sleep indoors and we both found ourselves sitting on a rooftop beneath the stars.

The Rif was still a wild place then—for my naive, barely-out-of-adolescence self, anyway. The indigenous Berbers, also known as the Amazigh, had been fighting off various armies and empires (from Romans to Arabs) for generations. At that time, a few years before 9/11, the region had only barely come under the taxation and census authority of King Hassan II. The long, bumpy bus ride that had brought me here passed steep hillsides covered with marijuana plants and opium poppies. The fields were guarded by bored-looking teenage boys who stood by the side of the road, leaning against trucks in the blazing sun and limply holding assault rifles. Those kids were the only people in the area with guns, as far as I could tell. I hadn't seen a cop or a soldier for days.

I was young and dumb, and had no idea what I was doing, but I'd come to Morocco with what felt like decent intentions. I'd spent the past year living as an illegal immigrant in Manresa, a fading textile town about an hour north of Barcelona, where I got an under-the-table apartment and under-the-table work as an English tutor. I lived in the cheap, crumbling section of town—my girlfriend and I boiled water on the stove to take baths and ate dinner by candlelight when we couldn't afford the electricity bill. But it was gorgeously picturesque in a cobblestones-and-feral-cats kind of way, and largely populated by North African immigrants who commuted around the region to build condos and office buildings for Catalans, many of whom loathed the newcomers. The anti-immigrant rhetoric at the time was nauseatingly familiar: According to some of my students, the moros were lazy, smelled funny, and reproduced at a frantic rate to spite the taxpayers of their host country. Those newcomers also happened to be my neighbors, friendly faces at the local markets and the corner bar where the clientele drank a little beer but mostly smoked cigarettes laced with a sweet, crumbly, light-brown hash. Like many of them, I was also undocumented—but, because I was a white American, I didn't have to worry. When anyone popped through the front door to say the police were coming down the street, and half the room bolted for the back exit, my job—as hastily explained by the barman, Adil, the first time it happened—was to sit tight, smile, and let my face lend the joint some legitimacy in the eyes of the cops, who, as predicted, never once asked to see my passport.

After a few months of living on the periphery of that racial tension, I decided to go south and see where my neighbors had come from. I saved enough money for a few aimless weeks and took an overnight ferry across the Mediterranean.

An afternoon glass of tea in whatever town square I happened to find myself in became part of my solo routine. On that summer day in the Rif, there was drumming and singing coming from a nearby casbah—the guy at the cafe said it was a wedding. As I sat, five or six youngish men materialized and crowded into the chairs around me. By this point, I was used to this line of questioning: What was my language? Where was I from? What did I want? I lied, as usual, speaking a mix of Catalan and Spanish. (Back in Manresa, Adil said that if I ever got to Morocco, I should adopt a non-American identity. The only tourists who had it worse than the yanquis, according to him, were the Japanese and the Germans—in that order.)

They smelled my bullshit. "I used to work near Barcelona," one of the older guys said and smiled. "You don't look Catalan. You don't sound Catalan."

I shrugged, thinking about an exit strategy, when a wasp stung my left bicep. At least it felt like a wasp. When I yelped and looked over, the guy to my left held up a cigarette and grinned. Apparently, he'd burned me. He didn't look that sorry about it.

Things seemed to be taking a turn for the ugly, so I gulped down the rest of my tea with what I hoped looked like calm confidence, said I had to go, and groped around in my pockets for money to leave on the table. Then it happened: an unpleasant tingling at the ends of my fingers and toes. I stood up. My legs were rubbery. My vision was getting smeary. The men looked at me expectantly. My first thought was the tea—the guy on my left had burned me so another could slip something into my cloudy drink. Or something.

I ran.

Their shouts seemed to follow me for a few seconds, but I didn't look back. Up until that point, I'd never once made it to my cheap guesthouse—which was embedded in a web of tiny, twisting, centuries-old streets—without getting at least a little lost. Not that day. I ran without thinking and did not take a single wrong turn.

I banged through the front door, up the stairs, and into my teeny room, bolted the door, whipped off my belt, and looped it around one of the bedposts and the handle to the door, which opened outward, buckling it tight. I didn't really suspect the portly stoner who ran the hostel—and who, just that morning, had insisted I sit next to him and explain the lyrics to "Hotel California"—was in on this sudden crisis. But I wasn't taking any chances.

When I woke up, it was dark, my skull ached, and my mouth felt like a lint trap. I hid in my room until dawn and took the first bus out of town. I didn't even consider telling anyone what had happened.

I kept heading south, to a bigger city, but quickly slid into full-time paranoia—every glance from a stranger felt like a threat, every interaction was fraught with panic. I was afraid of everyone and everything and spent more time than I'd like to admit squatting on sidewalks within a quick sprint of wherever I was staying, too ashamed to spend the day hiding in my room but too scared to actually go out into the world. I began collecting scraps of newsprint, pebbles, and other street trash as souvenirs. When I first got to North Africa, I was a magnet for hustlers and touts—now everybody pretty much left me alone. I'm guessing they could see I was not well. I abandoned the trip and bought a multiday bus ticket back to the coast.

The few people I forced myself to interact with were indescribably kind, offering me food, water, and assistance in a pitying kind of way. I think they also could see that I was severely jangled. The long-haul bus driver—a middle-aged man with kind eyes and a droopy mustache—insisted that I sit right behind him for the ride back north and would shoo away anyone he thought might be trying to bother me. I got back to Spain, checked into the first hostel I found, went to the bar on the corner, ate more sandwiches than I thought was possible to consume in one sitting, drank a few glasses of wine, and retreated to my room for a long, long sleep.

That's the story as I remember it, and as I tell it. But I've come to hate it because I don't like the way it sounds: Young white naïf goes to wild place, is targeted by scheming locals with some terrible intent—robbery, ransom, rape—and escapes courtesy of his quick wits and derring-do? That could've happened. I can't prove it, and it sounds like a self-centered and shitty Hollywood version of events, but it felt like what was happening at the time. Here's the other possibility: Young white naïf goes to unfamiliar place, feels overwhelmed by foreignness, is accidentally burned by a cigarette, then flees the country.

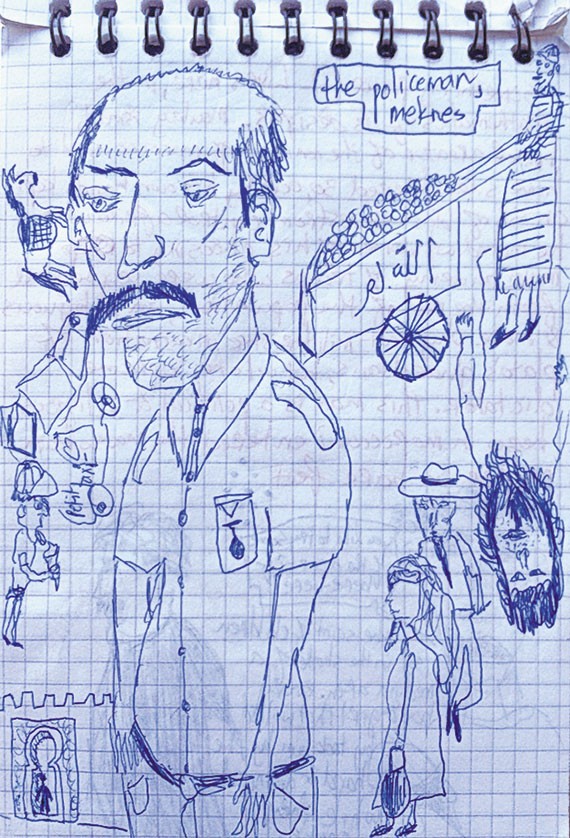

Both versions of the story are pathetic—either way, I panicked—but I'm grateful it happened. I could've larked around North Africa for a few more weeks, visiting castles and gawking at donkeys and writing bad poetry. But it wasn't until the crisis that I really noticed where I was and who surrounded me: the sad-looking cop on the corner in Meknes, the old lady who offered me an orange, the protective bus driver. Those stories aren't as exciting to tell at parties, but in retrospect I realize I only really started paying attention to the world when I was humbled and reduced—forced, for the first time in my life, to actually rely on the kindness of strangers.

Maybe that's the story I'll tell from now on. ![]()