Kate Rich has seen what happens when people get priced out of the housing market. Two years ago, she was living in Seattle and working as an advocate for homeless people when, she told me, "All my clients were like, 'Damn, I should have bought a home when I had a chance.' I realized that if I didn't do something, that was going to be me."

Rich knew there was no way she was going to be able to afford to buy in Seattle, where the median home price, at the time, was approaching $800,000. Places farther out in the county were almost as unaffordable, so she joined the flood of Seattle residents who've been priced out of the city and relocated across Puget Sound to Bremerton, the largest city in Kitsap County.

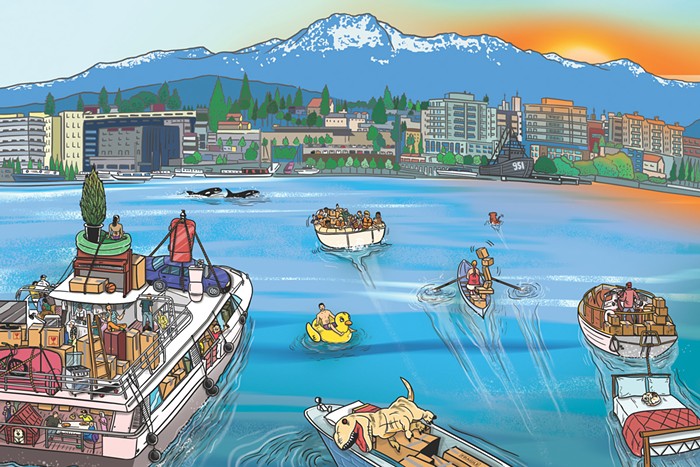

For people like Rich, Bremerton—a working-class city just 15 miles from Seattle—can feel like an oasis: It's scenic, with ample shoreline, city parks, green spaces, and a small but growing arts and food scene. But the big driver of relocation here is that it's cheap—at least by comparison. As of fall 2019, the median home value in Seattle is $714,000, which is down significantly from the peak of $820,000 in 2018, but it still means purchasing a home (or renting one) is out of reach for working-class people. In Bremerton, by comparison, the median home price is currently $312,000.

Your money goes further across the Sound, too: Bremerton homes cost, on average, about $200 a square foot; Seattle homes are nearly $500 for the equivalent. For people like Rich, who was going to have to leave the city if she ever wanted to buy a home, Bremerton was the obvious solution.

But the influx of people from across the water has not come without a cost. And while Bremerton can feel like the last affordable town on Puget Sound to those coming from Seattle—for the locals, this stream of newcomers can feel more like an invasion.

One of Bremerton mayor Greg Wheeler's first acts after being elected in 2017 was to end a marketing campaign his predecessor Patty Lent had implemented called "Move to Bremerton" (presumably a nod to the 1996 MxPx song of the same name, although I'm not sure if Lent is a fan of Christian pop-punk).

"I would like young professionals and young families to move to Bremerton," Lent said in the ad campaign over aerial shots of the city. She talked about the opportunities and affordable housing stock. While it may have attracted some of the young professionals Lent was trying to woo, many locals hated it. She lost her bid for reelection by more than 10 points.

"I don't want to speak poorly of my predecessor, but [the campaign] was ill-conceived, ill-timed, and thoughtless," Mayor Wheeler told me in an interview. "How does it feel if you are recruiting people to move to your community when there are residents just trying to make ends meet? It made no sense, and the migration was already happening. Why add to it?"

Of course, gentrification isn't bad for everyone. In addition to revitalizing blighted areas (of which Bremerton still has many), property values go up, and homes purchased 10 or 20 years ago have doubled, tripled, or quadrupled in value. Just five years ago, the median home price was less than $200,000, and the rise in values has been a welcome development to many who already own homes.

The city also has more life now: Downtown is still mostly empty after 8 p.m., but there are cafes and bars and vintage stores and two movies theaters—one for blockbusters and one that's more artsy—and there's the Admiral, a music venue that might not attract Simon and Garfunkel but did recently host The Simon & Garfunkel Story. There's also a brand-new co-op where you can buy locally foraged chanterelles and $6 gallons of milk.

Artisanal milk and hand-foraged mushrooms, however, aren't much comfort for people who have been priced out of their hometown. So instead of recruiting new residents from Seattle, Mayor Wheeler decided to focus on the people who are already in Bremerton.

And they need help: According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, more than 30 percent of Kitsap County residents rent, and the average apartment unit is now nearly $1,500 a month, a 60 percent spike from just five years ago. For those making minimum wage, it would take a 75-hour workweek to afford the average one-bedroom apartment. The city does have a rental-assistance program, but all too often, the math just doesn't work out, and homelessness has increased all over the county.

Lanette Duchesneau, owner of the Salad Shack, knows this firsthand: After 15 years of renting the same house, her landlord raised her rent from $700 to $900 in 2016, and then, earlier this year, kicked her out. Now the same property rents for $1,900. Duchesneau looked for a place in Bremerton, but nothing was affordable, even with a Section 8 voucher for just over $1,000 a month. Now she's staying with her daughter in Poulsbo. "I put my entire life in a storage unit," she said, tearing up. "It weighs on you."

Duchesneau is part of the invisible homeless, but the visibly homeless population has increased in Bremerton, too. Some locals also blame this on Seattle, assuming that transient populations are taking the ferry over and setting up camp. "We're getting the spillover from Seattle, with folks coming over that are addicted or tending toward criminal vagrancy," Mayor Wheeler said.

This may be true, but according to Nathan Sylling, program director at the Kitsap Rescue Mission, a 26-bed shelter downtown, it's a small part of the homeless population seeking services.

"We mostly serve people from Bremerton and different towns in Kitsap County: Gig Harbor, Port Orchard, Poulsbo," Sylling said. "It's often families who have been priced out or are on Social Security and are living in their cars." There is a small number of people coming from King County who may have exhausted their resources on the other side of the water, he added, but that's not the majority of the shelter's residents.

Wherever the homeless people are coming from, the population is increasing. "In 1993, we might have had three homeless people downtown and we knew them all," says Chief Jim Burchett, who has served on the police force for nearly three decades. "But in the last five years, there's been an explosion."

This "explosion" has led to the perception among some locals of increasing crime, but despite the overall population growth—as well as the increase in homelessness and the opioid crisis, which has impacted Kitsap County as it has much of the United States—crime in Bremerton is actually down.

"In the 1990s, we had a violent crime rate that was one of the highest in the state, but it's nowhere near that now," Burchett says. The data bears this out: While Bremerton, a navy town since the beginning, has been plagued by crime and violence off and on since its founding (and was particularly hard hit after the 2008 recession, when houses all over the city were foreclosed on), for the past five or so years, both property crime and violent crime have declined.

"People have short memories," Burchett said. "This is a pretty darn safe town."

For newcomers from Seattle, the idea of Bremerton as dangerous or crowded or expensive does not compute. Many of us feel secure leaving our houses unlocked, and the buses that leave from the ferry terminal in the evening actually drop passengers off on their streets. You tell the driver your cross streets, and he or she takes you right there. It's like a citywide school bus, albeit one that frequently drops people off at the neighborhood bar. How dangerous, and how crowded, could a town that adorable be?

Like Kate Rich, the impetus for my move to Bremerton earlier this year was money: My rent for a moldy one-bedroom apartment in Seattle's Central District was $1,850. And if my landlord wanted to double the rent or sell the building, I had no say in the matter. It was her property, and she could do what she wanted. Living like this wasn't just unaffordable, it was unstable. And so, after 18 years of being a renter (a period in which I moved 16 times), my girlfriend and I decided to buy a house. While I'd never particularly dreamed of owning a house, I do dream of someday retiring, which I feared would never be possible if we continued to rent in King County or anywhere else. It was time.

The problem was, like Rich and so many others, we could barely afford a parking spot in King County, much less a house. We looked at a few condos around town, but after HOA fees, they might as well have been in Bill Gates's zip code. This could change as Seattle builds more housing and prices drop, but we couldn't wait for that, so we decided to look in the other direction.

We took a first-time home-buyer's class and found a real estate agent in Kitsap County (a delightfully suburban woman who goes to Starbucks four times a day). And after a few weeks of exploring neighborhoods and checking out homes, in April we bought a 1940s bungalow with a view of Mount Rainier from one side and a view of Puget Sound from the other. We have a massive yard (by city standards), and it's so quiet that we can hear the bugle call from the US Navy shipyard every morning. We can walk to the water, the sunsets over the Olympic Mountains are Lisa Frank pink, and for all of this, our mortgage is still less than our rent was in the city.

I thought I would miss Seattle—the food, the weed, the $5 talks at Town Hall, the sense that I lived in a place where things were really happening. The idea of moving out of the city was almost a blow to my ego. What was next, a Costco membership? (Yes.) But six months after the move, I wish we'd done it years ago—and not just because our house would have been $100,000 cheaper.

It's not perfect, of course. Good luck finding food outside of Safeway past 10 p.m., and the only decent pizza place is open one night a week and stops serving as soon as the dough runs out. The skating rink got sold and turned into a storage facility over the summer, and none of the libraries in Kitsap County have the Philip Roth book I've been trying to get. (The one in Bremerton, however, does have a genealogy center, which I figure will keep me busy for at least a winter.)

And then there's the commute. There's a much-lauded 30-minute fast ferry, which former mayor Patty Lent pushed for, but reservations are nearly impossible to get and the boat bounces like a plane in a lightning storm. Most days I take the big boat (or the "slowpoke," as I've taken to calling it), which is a solid hour each way. Add in travel to and from the ferry terminal, and I'm in transit roughly three hours a day. And that's on the lower end for Kitsap County commuters. I live and work within a couple of miles of the ferry terminal on each side. For many commuters, travel time is easily more than four hours a day.

And yet, I'd rather do an hour on the ferry than 15 minutes on the city bus. You can nap or walk laps around the boat or drink beer and wine with your ferry buddies in the galley. Or you can work. There's no wi-fi, but I turn my phone into a hot spot, which sort of works, and for two hours a day, I have a mobile writer's retreat in the middle of Puget Sound.

The ferry can certainly get old—especially at night, when all you want is to be home—but on clear days, the views are stunning. I take endless photos, trying to capture the landscape and make my friends back home jealous on Instagram. Unfortunately, Mount Rainier has this strange habit of shrinking when my camera is pointed at it, and photos really cannot convey the scene's beauty. (On cloudy days, when the mountains have disappeared into the fog, there's always the rich people's houses on the south side of Bainbridge Island to spy on. They're impressive from a distance but even bigger when I remember to bring my binoculars.)

And there's the wildlife. On my very first commute home after we moved, I saw a whale breach not 20 feet from the boat. It was fucking magical, and the feeling was only slightly diminished when I woke up the next morning to the news that a ferry had hit and killed a whale the night before. That would never happen on the light rail or the bus.

That sense of magic—the feeling that I've landed someplace special—hasn't faded. Bremerton still feels like an oasis. It seems like every time I leave my house, I find something I hadn't known about before, be it some hidden park or a Filipino cafe with perfect—and cheap—lumpia and pancit. It can feel at times like I've stumbled into Puget Sound's affordable Lost City of Z, but I know I haven't really discovered anything. I'm just another gentrifier, come over from the city to claim my little slice of equity. The more people like me who move in, the less space there is for the people who were here before.

This is a problem that Joey Veltkamp and Ben Gannon think about, as well. The two artists moved to downtown Bremerton in 2017 after their building in Seattle was sold and converted into Airbnb units. Every six weeks for the past two years, they have turned their home in Bremerton into an art space and gallery they call cogean?, after the name of their street. (Veltkamp says there's a question mark in the name because the gallery "began as an inquiry: Will old art friends still visit us out here in Bremerton? What's happening in Kitsap's art scene? Will Bremerton come say hello?" He also noted that everyone pronounces the street name differently, and the gallery name is lowercase, italicized, and punctuated for "maximum artistic pretentiousness.")

I first met the couple at an art opening at the gallery in June. They'd pushed all their furniture into the back rooms for the show, and the featured artist was Izzie Klingels, a Bremerton illustrator whose intricate pointillism looked like portraits floating in space. The hosts served beer, wine, LaCroix, and little Japanese crackers, and the atmosphere was intimate and familiar.

Veltkamp and Gannon were immediately welcoming, and when my girlfriend and I told them we were new in town, they introduced us to their friends, most of whom, like us, had moved from Seattle. Everyone asked the same two questions: How long have you been here? How often do you have to go to the city?

A few months later, I caught up with Veltkamp and Gannon on the 7:20 a.m. ferry into Seattle, where they both work day jobs. The sun was breaking over Seattle and bouncing off Mount Rainier. All around us, people snoozed or stared at their phones or drank coffee and enjoyed the view. The couple was getting ready for the last show at the gallery—after two years, they are ready for a break and for their house to be just their home—and we talked about the ethics of moving to a place like Bremerton when that can mean pricing out locals.

"We try to live up to the idealized version of what a good neighbor is," Gannon said. That means developing real relationships with neighbors and not trying to impose their values on the people who were here first. If someone wants to play Pete Seeger out loud and all day, they're into it. They don't just say "hi" to their neighbors, they actually get to know them. They help them out, lend them ladders, cook them casseroles when something goes wrong. When I ask if they would have ever done that in Seattle, Veltkamp says no way: "We didn't even know the people in our own building."

Becoming the idealized version of a neighbor has been our tactic as well, as it has for Kate Rich. In Seattle, I rarely interacted with the people who lived around me. Mostly they annoyed me, which tends to happen when you share thin walls with people who snore or have loud vibrators. But in Bremerton, I go out of my way to make friends.

This means doing things I never would have done just a year ago: walking my elderly neighbor's dog, watching Seahawks games with the people down the street, and even—much to my shock—going to church. It's not about God or religion for me, both things I have little faith in, but about something much greater: finding community.

And it's happening. On the commute back from Seattle after Rich told me her story, the ferry rounded Bainbridge Island and the sun setting behind the Olympics made all of Bremerton glow. We were home. The idea isn't to change Bremerton, it's to let Bremerton change us—and it seems, somehow, to be working.