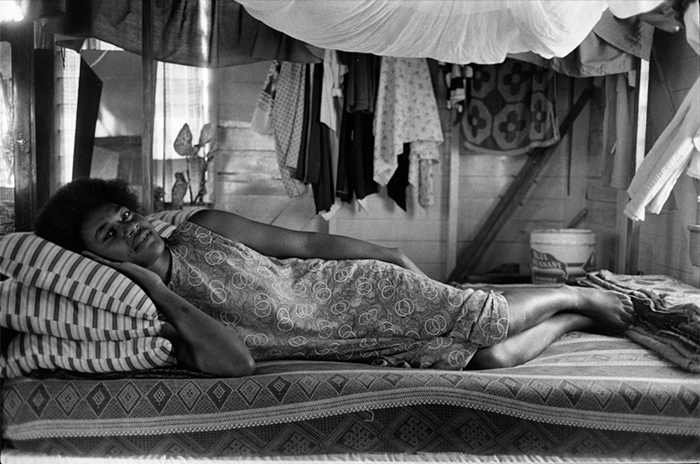

Employing a classic gambit, the film proves this by examining in depth an act of the greatest evil. In the Northern French countryside, a land seen as thick-clotted muddy fields under sheet-metal skies, someone has raped an adolescent girl and dumped her half-naked body for the ants to crawl over. Policeman Pharaon De Winter (Emmanuel Schotté) is assigned the case, but he seems helpless when confronted by such brutality. His investigation consists of doing precisely nothing; some questions get asked of potential witnesses, but De Winter mostly wanders about town, staring at the brick walls, the sea, or his neighbor Domino (Séverine Caneele) with the same bemused expression of a child puzzling out some adult mystery.

Permanently wide-eyed and tight-lipped, Schotté--like all of Dumont's cast, a nonprofessional--does not give a performance; in fact he barely registers as a presence. Several critics have praised his acting, but his work is more remarkable than just playing a part; he barely exists at all, except as a shambling, stooped-over body standing in for us. This is necessary for Dumont's ruminative, exploratory method. Dumont is not yet enough of a master to earn his numbing pace, but he's grown since his impressive but ragged debut, La vie de Jesus. Toward the end of L'Humanité, a sudden shot of flowers seems the loveliest, most colorful image you've ever seen, its vibrant reds a redemption of the bloodletting that set the film in motion. Dumont is still fumbling and obvious at times, but it took a truly great director to see that bouquet. If Dumont can nurture his talent and maintain his outsized ambitions, this could be the start of an amazing career.