"We don't say 'break a leg' in lucha libre. We say 'good luck.'"

The line comes from Cassandro, a famous and flamboyant lucha libre wrestler known as an exotico, which is a wrestler who fights in drag. He's talking to Marie Losier, the documentarian behind Cassandro the Exotico!, a brisk and shimmering 16-millimeter film about Cassandro's radical success as the "Liberace of lucha libre."

"Good luck," Losier says to Cassandro, before he goes off and kicks someone's ass wearing a sequined robe with a train that would make Princess Diana jealous.

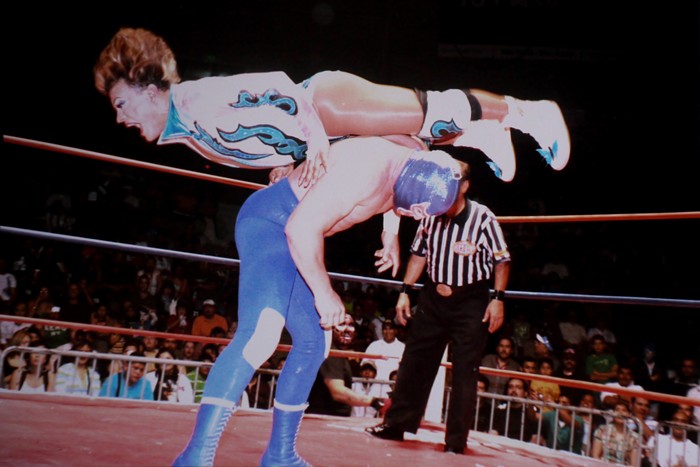

Lucha libre, as Cassandro explains, has included exoticos since the 1940s. In the past, exoticos performed mostly as clowns, but Cassandro says he's changed the game. In 1992, Cassandro won the Universal Wrestling Association World Lightweight Championship as an exotico, which he claims not only changed the Mexican sport, but also "changed the Mexican culture." Thanks to Cassandro, exoticos now get to beat the shit out of people.

Drag and wrestling might seem like two ends of a spectrum, but the practices are more siblings than rivals. The similarities are everywhere, if you think about it. Both explore hyped-up versions of gender. Both are often incredibly choreographed events meant to seem natural, heroic, even divine.

And, of course, there are the injuries. In wrestling, there's the suicide dive, a headfirst running dive outside of the wrestling ring. In drag, there's the dip (usually referred to as a "death drop" on RuPaul's Drag Race), which has famously injured queens. Cassandro himself has too many injuries, and most of the documentary is spent detailing the overwhelming toll lucha libre has taken on his body.

It should be noted that Cassandro's exotico drag is different from the drag that's become common in the U.S., largely thanks to RuPaul's Drag Race. While Cassandro doesn't wear a mask like a luchador, he also doesn't wear a wig like a traditional drag queen. Cassandro's exotico drag is mostly a femme presentation with flamboyantly colored tight-fitting fabrics and gaudy, flashy makeup. His hair is propped up like a rooster. (As he explains, "My hair is my mask.") And he uses he/him pronouns even when performing and wrestling.

This counters the common understanding of drag in America, which is often that "drag is men pretending to be women." But drag doesn't exclusively operate on a binary. Any costume or fashion that explores gender in a performative way can be considered drag. Using this framework, Cassandro is drag. His ambiguity makes him even draggier.

The novelty of seeing a drag performer wrestle is worth the price of admission, but the best moments of the film come from Losier. Known for her short films, Losier seems to have snuck a few shorts inside Cassandro the Exotico!, which frequently pivots to surreal shots of Cassandro walking through the desert in his exotico costume or being carried by a team of luchadors. These scenes are theatrical, even regal, and avoid pretension. Losier conjures the legend of Cassandro with overwhelming affection. It's a lovely, fantastic spectacle.