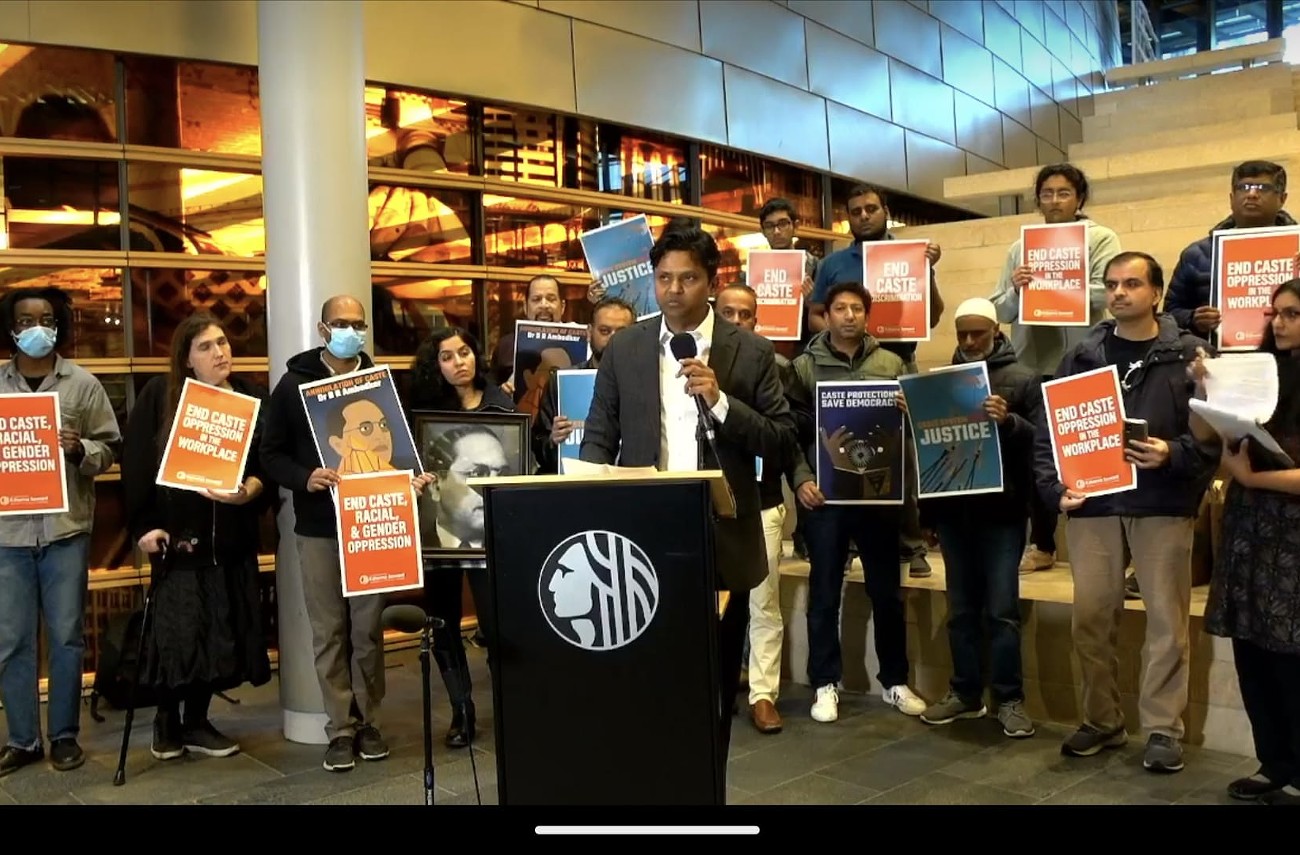

On Tuesday, the Seattle City Council will consider an ordinance from Council Member Kshama Sawant to ban caste-based discrimination in Seattle. I’m calling on the City to pass this legislation to help protect people like me and to set a powerful precedent for outlawing caste discrimination nationally and internationally.

I come from a caste-oppressed community in India commonly referred to as Dalits, one of 300 million people who suffer poor living conditions created by thousands of years of so-called “Untouchability.” The horrendous system still prevails in South Asia, remaining one of the country’s fundamental faultlines–an original sin, much like race in America.

I grew up in the midst of this society, worked my way up, and managed to migrate to the US in the hopes that I would finally be free of the chains of casteism. At a recent public comment period in Seattle, I was reminded of how wrong I was.

During the testimony, I heard people opposing this ordinance label my community as a hateful group for merely demanding protection from deep-rooted biases that are produced from a society sick with the caste system. Those comments only validated my doubts and fears that my adoptive country barely understands Caste.

Casteists believe that contacting or socializing with people like me pollutes their lives and afterlives. Almost one in three dominant-caste households in India practice untouchability at personal level.

The silent support for caste is rampant. My people are forced into ghettos through socially enforced segregation. Like my Black brothers and sisters, we also suffer from inhuman stereotypes.

The people who testified against this legislation want me to believe that such minds were magically cleansed of these heinous ideas without any efforts upon landing in America. Sorry, but I am smarter than that.

When I first arrived in Seattle, it was clear to me that the Indian community would accept me as one of their own if I fit into their standards. The (now) 150,000-strong Indian American community is completely dominated by members of the dominant castes. Even though they form about one-tenth the population in India, thanks to their inherited social and material privilege, they form ~80% of the Indian American population, making my community a minority within a minority.

There are no visible biological markers of a person’s caste, but those who grow up in a casteist society are able to identify–with good accuracy–if a person is in-network or out-of-network.

Such networks are very strong. Social networks are caste-segregated in America, too, as indicated by the 2020 Indian American Attitudes survey by the Carnegie Endowment. Moreover, a University of Michigan study of matrimonial websites showed that Indian-Americans were much less open to intercaste marriages than individuals with identical demographics in India (~14% vs 23%).

Thus, to pass as a person from the dominant caste, people like me have to erase these markers and “fit in.”

Success in my career was my only way to stay safe from falling back into the miserable conditions waiting for me back home. I decided to never talk about myself and my caste background anywhere. Twenty years of a closeted existence, of hiding from myself to avoid direct discrimination, became increasingly difficult.

Constantly guarding my thoughts, my opinions, and my actions, I thrived professionally but struggled at a human level with my contradictions. Until recently, I did not even share with my children the superhuman struggles my parents and grandparents underwent to win basic rights for us.

It was at the height of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 that I could no longer hold this contradiction inside. I wanted to express solidarity with the Black community, so I went public with my identity. Embracing my real self has been immensely liberating. It has brought me closer to my community in Seattle, whose existence I was not aware of. I constantly meet people who, like me, stayed in hiding, unable to find each other for decades.

This is why I strongly support the ordinance outlawing caste discrimination proposed by Kshama Sawant. I do not want my children to live closeted lives in America the way that I had to. I am touched by the solidarity shown by working people here who can see the connection between the fight against caste oppression and the fight against other forms of oppression, such as racial, gender and class oppression.

I am also not surprised to see that there are right-wing bigots who oppose this ordinance. This is typical of any struggle for civil rights, and it is, again, why I urge Seattle City Council members to vote for the ordinance. Voting against it would be to stand with bigotry.

Samir Khobragade is a Seattle-based tech professional who has been working in the IT industry for the past 26 years. He lives with his wife and two children. He is also an anti-caste activist working with other local and national anti-caste activists for the Seattle ordinance