Here's the argument: The younger, straight boy hates the Olympia music scene. Its strict politics are overbearing to him; they make him feel excluded. The older, queer boy lived in Olympia during the crucial years, and he believes that its rock scene flipped the mainstream on its deformed head. He also believes there wouldn't be nearly as many female rock stars these days if Olympia hadn't made the river run the other way. Ultimately, the other boy doesn't get it, and the older boy, Shaun, is pissed and frustrated, just like a woman.

That is how I came to know Shaun Surething. After the argument fell away and all you could hear again were the quiet snips of scissors, I sat for a moment, awake with new breath. Then I pummeled Shaun with questions. There is something adamant, studied, and lacking in defensiveness in Shaun's feminism. As he speaks, his feministic energy rushes like a freeway.

Never mind that feminism is going through its Third Wave--the point is how it tumbles through the individual, and perhaps most tellingly, through individual men. When I am conveying a story of sexism, even to the most liberated of men, I often feel like I'm chasing ghosts. Talking to Shaun is markedly different. In casual conversation, he doesn't doubt the tiniest detail of the experience of a woman; he bears witness to the ways women are cut off or dismissed. He wonders why women who are murdered aren't considered victims of hate crimes. We have all memorized Matthew Shepard's name as an emblem of our liberal sympathy, but what about the women who were killed by the Spokane serial killer?

The Surest Moment

"I had just taken a huge bong hit when Kathleen Hanna walked into the room," Shaun says. "It was my 18th birthday. It was 1989." He and a bunch of guys had been cavorting at strip clubs around town (never mind that he's gay) and were back home--someone's home in Wallingford--to tank up.

Shaun hadn't met Hanna before. She wasn't famous yet: no Bikini Kill and not yet the Queen Bee of Riot Grrrl feminism. "My friend started making comments about the strippers--some easy, slutty hypothesis--just to get a rise out of her," he says.

Then, in a moment that is permanent in Shaun's mind, Hanna turned to Shaun and asked him directly, "Are you like them? I just want to know right now: Are you like them?"

Instantly sober, Sean realized that no, no way was he like that. He had never been like that in his entire life.

"I think about that moment a lot," he says. "It was one of my greatest epiphanies. I realized I wasn't a part of masculine culture--homo or het. I just wasn't included in that masculinity."

Women's Lib, Lesbians, and Candyasses

"My mother tried to send me to school in this hot pink T-shirt with big red lips that said 'Women's Lib' at the bottom." Sean exhales a jet of cigarette smoke. "I'd wear it now."

His feminism began with his mother. "She opened what I believe to be the first women's shelter in Yakima," Shaun says, "and later she helped start the first gay/ lesbian center at Central Washington University. A lot of what she was doing professionally spilled over into her relationships. I was around a lot of strong women."

He and his mother lived in a trailer house in Ellensburg. His natural father was gone by the time Shaun was two. "She was very connected to the lesbian/feminist community. And so I was connected. She raised me very much inside her peer group," he says. "You have to keep in mind that this was happening inside the working-class hillbilly mentality of Eastern Washington. And that was who I had to play with: kids who had guns at the age of five. All my friends, though, were girls.

"When I was young I believed women could do anything men could do; in fact, I believed women could do more," Shaun says.

But as a teenager, his relationship with his mother, and her ideals, turned sour. "When I was 13, my mother married the most stereotypical male nightmare," he says. "He was very domineering, and I got very confused at that point. Her social life was completely irreconcilable with her new marriage. And so I became disconnected from the feminist environment when she completely turned the tables. After the marriage, I was expected to work on the Ford pickup, hunt and fish."

Shaun gets another drink. As he sips his vodka, he tells the story of a two-day fishing trip he was forced to take with his mom's new husband.

"On refusing to gut a fish and after a bombardment of insults--'pussy,' 'faggot,' 'motherfuckin' candyass'--I threw all of his Schlitz Malt Liquor ball in the lake, tipped the boat over, and swam to shore.

"I started to feel distant from males, and I became very staunchly aligned with females," he explains. "I had the gut feeling something was wrong, but I now had the cultural belief that women were lesser or not strong."

Reborn

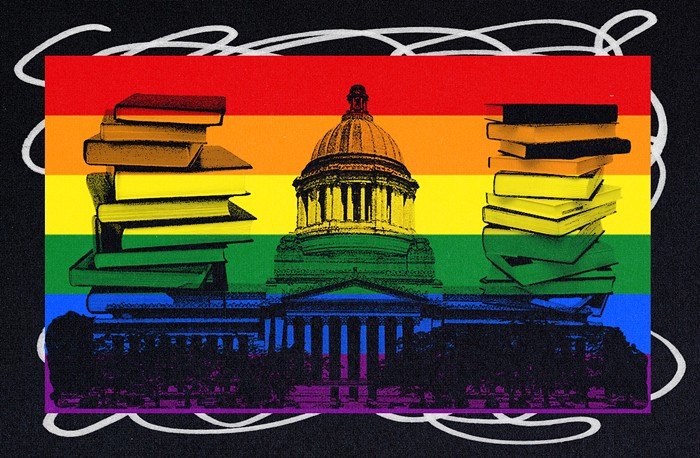

On a whim, Shaun moved to Olympia when he was 19. At that time, the Olympia scene was a wild animal bucking at the rules of mainstream society: Women were charged less for admission to rock shows, for example, as a response to the unequal economy.

"Riot Grrrl was a huge influence on me, with Kathleen being only one of a number of strong girls," he says. Finally, Shaun admitted to his friend Amy that he was still holding his mother responsible for what had happened; Amy said that was fucked up, and that he was blaming his mother for something a man had done. "She helped me understand that my mother was in an abusive situation too," he says. "It was another big epiphany. After that, everything started to fall into place."

Olympia's feminism resuscitated Shaun's childhood beliefs. "All the girls in Olympia made each other think, made me think, made everybody think--or shut the fuck up," he says. "The beauty of that scene was that it wasn't going to be derailed--even if that equaled its demise."

Down to our last pair of cigarettes and cocktails, I ask Shaun to turn to an imaginary camera and make his final plea to a captured audience filled with boys of varying ages and orientations.

"Shut up and listen for five minutes," he says.