On Wednesday, July 23, after The Stranger went to press, a city council committee met to discuss a proposal that would let developers build taller throughout the city in exchange for funding affordable housing and other public benefits.

The council probably won't decide how to divvy up those benefits until this fall, but interest groups—from historic preservation activists to arts advocates to rural conservationists—are already lining up for a slice of the pie.

One smart idea that shouldn't get shoved to the back of the line is transferable development rights (TDR), a wonky term for programs that allow landowners in rural King County to sell off the right to develop and subdivide their property to developers in cities like Seattle, enabling those developers to build taller buildings than allowed under existing rules. Once the right to develop a piece of land is sold, that land can never be subdivided and turned into suburban sprawl, which is in the process of engulfing rural King County.

Expect neighborhood groups to scream that preserving land in rural King County does nothing to compensate for added density in Seattle neighborhoods; already, community councils are gearing up to oppose height increases around the city.

"If you live in Greenwood and you get stuck with density, it's going to be hard for Seattle politicians to say, 'We made you take this density, but we saved this farmland out in Enumclaw,'" says Roger Valdez, a land-use consultant who supports TDR.

It may be a tough sell, but it's an important one. Keeping rural parts of King County from devolving into hintersprawl actually helps all Seattle neighborhoods, by reducing congestion, preserving rivers that provide Seattle's water, and reducing carbon emissions throughout the region.

And King County's rural land is disappearing fast. With farmland and forests being converted to five-lots-per-acre suburbs at a rate of between 4 and 5 percent a year, King County's rural lands could be gone within the next 20 years.

Tim Hatley, a lobbyist for the Cascade Land Conservancy, calls TDR the ideal sprawl-prevention tool because "It's a market-based solution," not a taking.

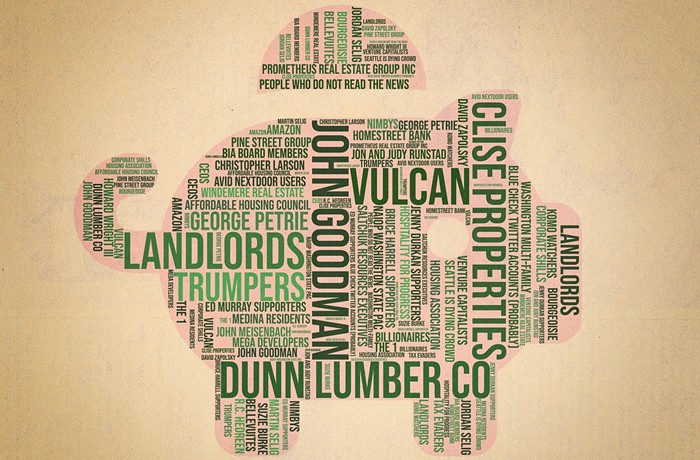

So far, Seattle has participated in just one TDR program, which enabled three developers, including Vulcan, to build above the height limit in Denny Triangle. But that program expired last week, and Mayor Greg Nickels has opposed replicating it elsewhere, preferring to invest in things like parks and historic preservation.

Those are worthy causes, of course—who would argue against preserving buildings threatened by development?—but the city has to prioritize. Once rural lands are gone, they're gone forever. That will impact all of Seattle unless the council steps up to prevent it from happening. ![]()