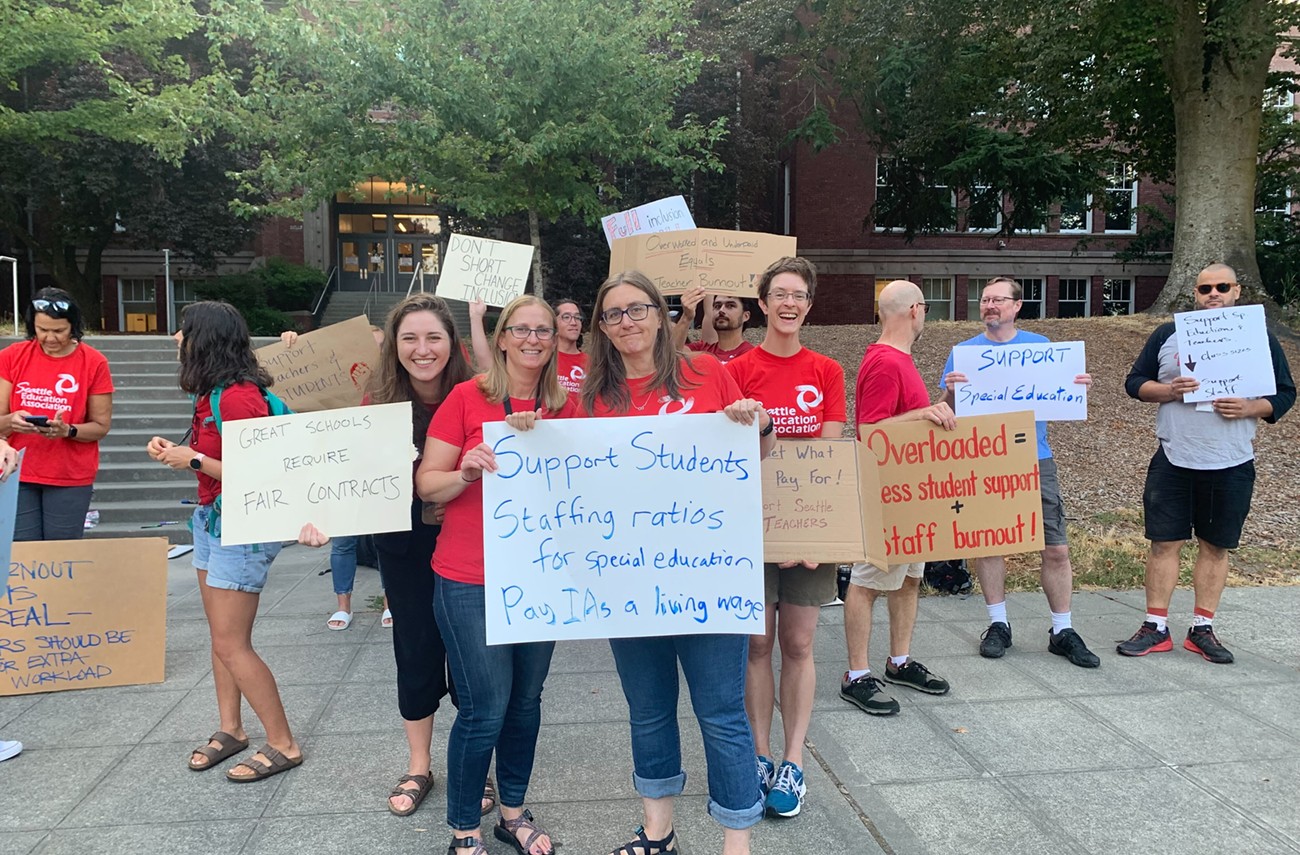

Wednesday morning, on the last day of their contract, the Seattle Education Association waved signs outside of many Seattle public schools to show the district that they mean business. With just one more day of bargaining left, the union is still not pleased with the district’s proposal for special education, which could lead to larger class sizes without the resources to accommodate students’ wide variety of needs. If Seattle Public Schools (SPS) doesn’t promise manageable class sizes, the union said a strike may be in order.

As it stands, SPS offers many special education programs, but the district’s proposal would make drastic changes to three major program models that have broad names: resource, access, and social emotional learning.

According to the district’s proposal, students in the “resource” program have “mild to moderate differences” in their instructional needs and spend most of their time in general education classes. These classes have one teacher for every 22 students. Students in the “access” program have “moderate to intensive academic and functional needs.” These students have more access to their teachers, with one teacher for every 10 elementary students or 13 secondary students. Finally, social emotional learning classes have one teacher for every 10 students.

These programs cover a wide swath of needs, from dyslexia to autism to post-traumatic stress disorder. Under the district’s new “Collaborative Teaching” service model, which will gradually roll out over the next three school years, all of those students would be in the same program with no specific cap to the staffing ratio.

“The biggest fear is that our students are going to be in inclusion classes without the support they really need for differentiated instruction, and it's going to be impossible to give them all the support that they need,” said Meredith Hoban, the Special Education department chair at Lincoln High School.

Not only would it be difficult to adequately teach students with various needs simultaneously, but the paperwork would be an absolute nightmare, making for “unsustainable” working and learning conditions, Hoban said.

SPS is on a different page. In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for the district said the proposal is “aligned” with the district’s “instructional philosophy that puts students first, creates inclusive learning spaces, and provides educators and staff with generous compensation, including professional development, career opportunities and benefits.”

The district almost convinced Summer Stinson, an education advocate and a mother of a child with special needs. Stinson said when she first saw the proposal, the language of “inclusion” and “individualization” excited her. But she quickly realized the move could allow special education students to be in classrooms with 30 to 40 kids, like general education students, which would in effect do the opposite of offering highly individualized learning.

“All students deserve smaller class sizes, but special needs students most of all,” Stinson said. “This proposal is like playing musical chairs with our kids and our limited resources. The district won’t put out enough chairs and then, when the music stops and some kids don’t have a chair–oh well!”

Hoban said that the union wants to keep caps on the caseloads of special education teachers. In some cases, the union wants those caps even lower. Hoban said they are pushing the district to lower the cap for “resource” students from 22:1 to 18:1.

Additionally, the union demands that the district pay special education teachers for the hundreds of meetings each year that they hold with students in Individualized Education Programs (IEP). Hoban said the district expects teachers to conduct those meetings outside of contract hours for no additional pay.

While the district said it “look[s] forward to bargain[ing] in good faith,” Hoban said if the district does not heed the teachers’ warnings about a proposal they describe as disastrous, then there’s a good chance the union will go on strike.

Of course, when teachers go on strike for better working conditions, they often face charges about them not actually caring about students. Hoban said that sentiment couldn’t be further from the truth. Advocating for better pay is far from selfish, she said. The union wants teachers to make enough money to live in their communities and stay at their schools as experienced educators. If the district refuses to pay a fair wage to its workers, Hoban said some of her colleagues will go to another district that will or else quit teaching entirely.

But from the signs the teachers held outside Lincoln High School, the union seemed much more concerned about their special education students. As Stinson said, the teachers union operates as the last line of defense for their students against a problem that begins far upstream with the state’s choice not to fully fund the true cost of special education.

“Teachers are the ones who have the futures of our kids in their hands right now. And they're doing what they can to say ‘No, this is a line you don’t cross,’” Stinson said.