The language of health and disease, the language of treatment, is a language we don't ever really know. We hope we'll pronounce the words right.

I was on a hospital gurney in a hallway, and I'd been there, confused, for hours. I was wheeled out there after a CT scan on my abdomen.

Am I okay, I'd asked the CT technician. She looked down at the floor.

"You're going to die," she said.

And then, animated, "Just kidding! The doctor will see you in the hall."

She patted me on the shoulder. That's the kind of person she was.

I was there after being assaulted by my boyfriend; it was the first and only time he'd hit me, and I promised myself I'd never see him again. I didn't have a job, I'd just finished grad school, and now my rib was broken and I had internal bleeding and bruised intestines that would scar up. I wasn't sure what was next for me. The CT scan was for my liver and spleen to make sure they hadn't split open.

My spleen was fine; my liver was fine.

"Your spleen is fine; your liver is fine," the doctor said. I was in the kind of pain that's not just dull or sharp but also frightening.

"The suspicion is that you have lymphoma."

I'd talked to this doctor hours ago, when I checked in for my injuries. We talked about police reports, and he checked my breathing.

What? I asked.

"Your lymph nodes are irregularly large; you'll have to get another CT scan. The suspicion is lymphoma," he said again. Suspicion. Was that a diagnosis?

A smiling nurse appeared next to us. "At least you caught it early!" she said. "Think about it! The assault saved your life!"

"You'll get that CT scan in a week," the doctor said.

The CT technician had told me more than one scan on my abdomen in a month was a cancer risk, but just one was safe, don't worry. I was 30.

Were they going to tell me they were kidding?

I shook my head. How do you know how big my lymph nodes are supposed to be? I asked them. You've never seen my lymph nodes before.

"They're too big," he said.

Could they be enlarged because of the assault?

"Lymphoma," he said. Just that one word.

"See you soon," the smiling nurse said. She handed me some forms to sign, and they both walked away.

The walls in the hospital were that hovering ghost color that makes you think you're dead, that you've been ground up and mixed into aspirin. This wasn't a dream, and neither was the "suspicion." A diagnosis hovered, demanding its shadow. Its shadow is treatment.

"Treatment" is a word made up of different words.

"Treat" is from the French traiter, derived from the Latin tractare. To handle, deal with, conduct oneself toward, tug, drag about.

"Ment" is a magical suffix that turns actions into things. To add "ment" to the end of a word is to draw it into the world.

That means treatment may be "the state of conducting oneself toward something." That's as gentle as a quiet, correct step.

It also means that treatment may be "the state of being dragged about, the state of being pulled violently."

When we're sick, or when we think we're sick, we seek treatment. Since we all get sick sooner or later, treatment is a part of being human. It's not separate from our lives, it's not a feature of certain people's experiences, it's not optional.

Writer and intellectual Susan Sontag, in her book Illness as Metaphor, wrote of this obligation to be sick in our lives. And she also wrote that to decorate our illness with metaphors and melodramas was to make matters worse. "Illness is not a metaphor," she wrote. "The most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking."

For her, stripping illness of its storytelling power was a treatment.

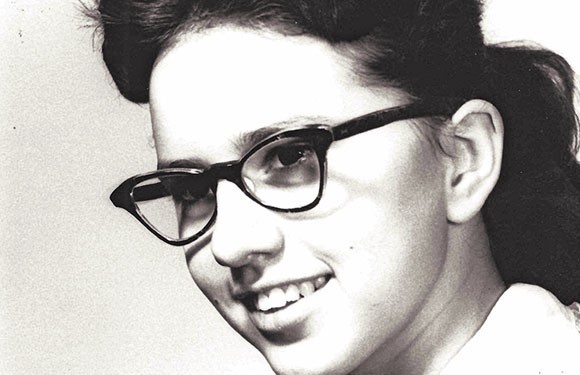

None of this will tell you enough about her, but I'll try:

Susan Sontag wanted us to live serious lives. She wrote brainy novels that I loved more than most critics did. She had a shock (and that is the right word for it) of moon-silver rushing through her black hair. She was a radical who said that for art to be relevant, it must have enemies. She made enemies. "I am aware of what a radical point of view is; very occasionally I have espoused one," she said wryly in an interview with Salon, after she was publicly attacked by pundits of all sorts for questioning the United States' foreign policy shortly after September 11. She died in 2004, and some of the obituaries were angry. They couldn't cope with her life, in which she tried to cope with her own "radical political convictions and sense of moral dilemma at being a citizen of the American empire." She wrote (desperately, she later confessed in an interview in the Threepenny Review) about the gestures and effects of a "radical will." The will was important. The will to live, to create, and most of all to disrupt. Essays by writers who are still tangled up in her work—who she was, how the world could allow someone so beautifully contradictory, so caring and angry, so joyful and serious—are still coming out all the time. We can't stop thinking about her. She would have liked this, but perhaps pretended to not have noticed.

She was diagnosed with cancer on three different occasions. First, breast cancer in 1975. She responded to it with Illness as Metaphor, a radical mastectomy, and chemotherapy, which she opted for over a "modified radical" mastectomy, which was a less invasive treatment. She viewed cancer as a growth, so radical treatment was necessary to getting to its root (radicalis from the Latin radix or "root"). An extremity of uprooting. When a friend came to her with a cancer diagnosis and fears about the pains of treatment, she told him that when he was in such terrible pain that he may have to stop, that's when he should take another treatment. Then another. She was expressing sympathy by encouraging defiance. I wonder why she didn't notice that her approach to treatment echoed perfectly her approach to living, and so was alive with metaphor.

Radical in her heart, radical just above it.

She, we, can't stop thinking of treatment as a sweeping rescue, either false or true, radical or conservative, malignant or benign. Just as we are obliged to be sick, to seek treatment, we are so obliged to find our own meanings there.

Death, like treatment, is another non-option. An unwinnable argument.

Death comes, and when it does, it sounds like a creaking door. I know this because when my mom was finished with cancer, a noise uttered its way past her teeth. Like something being crushed slowly, but there was no burst or relief at the end. She died on a bed in our house. She'd spent a lot of time before that moment disappearing. No more fat or muscle on her, no more talking; she was like a piece of paper with bones in it. Each breath was a disjointed heave and hiss, and then it stopped.

I was 24; she was 56.

None of this will tell you enough about her, nothing could, but I'll try:

My mom would tug at my sister's hair or pinch me when we misbehaved, because she was a big sister to us. Her mother died giving birth to what would have been my mom's first younger sibling. My mom corralled and held us against harm. She wouldn't let us watch violent movies. She wrote a short story about a woman who slit her wrists in a library and everyone walked by quietly, trying not to notice. She read a lot. She gave classes for women at Barnes & Noble. She told me that as a little girl, she had a dream about looking out her open bedroom window as nickels rained in from the sky until the entire room was full. Sometimes she'd make me or my sister or anyone laugh so hard that we couldn't breathe. She had a John James Audubon bird book that she'd pull off the shelf and page through with me: the colors and the brushstrokes and the scenes of struggle and beauty.

They'd told us she had cancer, bone cancer. First it was breast cancer, and then it was bone cancer. Ten years ago, they amputated her fleshy left breast. She said that on surgery day, she put a sticky note on her breast that read "Good-bye." Treatment came to a temporary halt in a curved line of black stitches across her ribs. That should be enough, but no! A breast wasn't enough for them. Not the cells, not the doctors. Ten years later, there was a tumor on her sternum, and then her leg. Then she was in pain. Constant pain. From diagnosis to death, it was a little more than two years.

For the period of time before her death, she took hold of this thing called treatment, which was an embracing bedfellow, a changeling that appeared to lie next to her until the end. If you are terminally ill or just uncomfortable, you or someone else, maybe your doctor or your family, will demand you get it.

My mother tried a few things.

She loved gardening, and it was in the garden she felt that first pain of the second cancer.

"I told myself it was from pulling the weeds too hard," she told me later, scolding herself. She waited for the pain in her chest to go away. It didn't. She went to a massage therapist who told her, "You should get this looked at." She didn't. Not right away.

The first treatment is one we administer on our own and continue to administer throughout illness. A symptom arises, and then we treat ourselves by deciding what we think about it. "It's nothing," we might say. Is a pain that we call "nothing" a metaphor? Sometimes this is enough, because sometimes—usually—the symptoms do indeed go away. The symptoms are symptoms of "nothing."

But the first treatment is like standing on the tip of a pyramid. Hope, delusion, and reasoned expectation all meet in a point. Which of the three faces will you tumble down when you lose your balance?

Of the three faces of that first treatment, hope is the most frightening. Delusion finds its end, somewhere. A doctor, a new symptom, a new pain. When you treat your illness with hope, you might never stop falling.

My mother tried hope—which she later discovered was not actually hope at all—for a long time. Too long, some people have said to me. She "should" have gone to the doctor sooner.

You hear "should" quite a bit. "Should" has for a while now been the sine qua non of treatment and, to a lesser extent, illness.

There is, first of all, the idea that treatments should work.

The radiation therapy was meant to shrink the tumor in my mother's sternum. It did, but then cancer appeared in her leg. Lymph. Lungs. While she was getting radiation, the hair brushed off her head. Her skin was burned terribly. She was constantly vomiting into a bucket she kept near her bed.

She "should" have gotten chemotherapy, doctors said, friends and family said. But since she refused, the recommendation was radiation.

That is the other should of treatment. There are treatments you should engage with, treatments you should ridicule, treatments you should be afraid of. Everyone has their thoughts and opinions. Sometimes they will keep these to themselves. Usually they will slip out in a kind, submissive tone.

After the doctor gave me a diagnosis of lymphoma, I was too broken down to go back to the hospital. I didn't want to speak in their language of smiles and forms and suspicions again.

I spent hours looking up lymphoma and its symptoms.

When you're sick, you know it because your attention shows up, unbidden, somewhere strange on your body. In your aching forehead. In your laboring lungs. In a tumbling discomfort just below your navel. But many people who end up with a serious diagnosis had no symptoms. People fear seeing their doctor because they fear an unexpected pronouncement. The word origin of "diagnosis" is "to recognize." What is being recognized is the hope or curse instilled by a way of looking and thinking. When you find out you have or may have a secret asymptomatic disease, suddenly your attention shows up in the diagnosed location. You touch that part of your body. You look at it in the mirror. You think into it.

When this is the case, panic becomes a symptom of your illness.

And education becomes treatment. Maybe, you think, information will be a curative map. It will help you quell the panic and find the right next step. Many of us know the varying degrees to which this treatment makes things better or worse.

Looking up treatment was a treatment itself. Perhaps I could calm down if there were cures.

Night sweats, itchy skin, fever, abdominal pain, cough, fatigue, weight loss, rashes, back pain. None of these are disease-specific. I found myself suddenly scratching my legs more and waking up in the middle of the night. I found myself exhausted. Was it lymphoma or just "normal" or had I been hexed?

"You should calm down," one friend said.

"You should rest before you drive across the country," said another.

I didn't go back to the doctor. I wanted to escape everything, and I had to make sure I would never interact with my boyfriend again.

I put my things in my car and drove across the country alone, from Amherst to San Francisco, wondering if my back pain was from sitting or impending death. In one of those states in the middle, the ones that are so beautiful that they blend together and make you forget their names, I stopped my car and watched pronghorn antelope grazing. I'd never seen antelope before. The only sound was the wind, which rushed up fast like the grass was exhaling. Then I remembered: lymphoma. I wondered if the states were being granted to me, one by one, showing up to say good-bye or calm me down. I'd felt my lymph nodes in my neck every day. I still catch myself feeling them. I wonder how my hands got up to my throat, searching for something.

There was a feeling of spinning.

When my mother was diagnosed, she fled, too. She got in the car and disappeared, leaving voice messages for us where she was crying, telling us she loved us all. Escape from treatment is really just escape as treatment.

I brought a small rice cooker and a huge bag of brown rice with me. I'd decided to be macrobiotic. Diets that are supposedly curative demand your identity. I am macrobiotic. I am vegetarian. I am Paleo. When I called my friend Scott and told him about the lymphoma, he cried out in despair, "But you're vegan!" (I'm not anymore; I am an omnivore. But I was vegan then.) "You shouldn't get cancer," he despaired.

Was it too much soy? I wondered. Was it too much sugar? Too much alcohol? We try to figure out the cause so we can treat ourselves by removing the offending force from our lives.

When I arrived in San Francisco, I met with a former teacher, my favorite teacher as an undergraduate, funny and forceful. I told her about the assault, about the drive, and finally about the lymphoma.

"What are you going to do about it?" she asked.

I'd been thinking about it for a while. I'd thought about it in Ohio, I'd thought about it in Idaho, I'd thought about it in all the states.

Well, I said, I'm macrobiotic now.

The principle of macrobiotic diets as treatment was something like this: Food is broken into two categories, either yin or yang, energetically expansive or condensed. Too much of one or the other causes imbalance in your own yin/yang energy, so eat for balance. I don't know if any of this is true. In the frenzy of online information, it kept appearing: people cured by eating certain foods with certain shapes. It all sounds crazy to me now, but back then, when I cooked and ate, I felt present and calm. I prepared the rice in the rice cooker and cut carrots on a certain slant, and indeed we all say now with the certainty of a revelation that food is a treatment. Would I do that again? I have no idea. Should I?

I'd done other things too. I'd gone to a woman named Althea who did something called lymphatic drainage. That is, she said she manually drained my lymph nodes with a light touch, and they did feel smaller afterward. She had a sign in her kitchen that said "It's a good day to be a witch!" It was relaxing, and she gave me a brush afterward that she said I should brush my skin with to encourage lymphatic circulation. As I was leaving her house, she said, "You really should go to the doctor, though."

And I prayed. I prayed, I was surprised to find, a lot. There were moments of desperate, unhinged confusion. My whole life was changing.

"That's bullshit," that favorite teacher of mine said. "You do not fuck around with this. You should go to the doctor. You should go right now."

You should not fall for what other people call bullshit.

There was a strange woman who came over to my mom's house and snapped her fingers in what she said was a healing gesture over my mom's body. This was just before my mom's body started to disappear and she was still walking around looking like herself.

This woman, whose name was Rain, called herself a healer. Rain said she was in contact with the "Council of Twelve," whatever that meant. My mom already had the radiation therapy, which mostly just caused pain. My sister went to the hospital with her, and doctors stuck needles into my mother's lungs, and tubes filled up with fluid. They did it again and again: punctured my mom's body, drew out the fluid. My sister sat next to her, watching, with a feeling of no escape.

So my mom was trying other treatments. She sent money to a group in California that said they'd pray for her and do vibrational healing. Thinking of this is almost unbearable to me—my mom, sending out an envelope—because I can't help seeing her as a little girl, sending a letter to Santa Claus, and then feeling the world and its unresponsiveness. The world pouring nickels into her bedroom until there was no room left to breathe, the world walking by the girl with slit wrists in the library.

Why, she must have thought, won't anyone help me? What have I done?

Treatment contains a promise that you will be helped, that the world will help you.

I watched Rain make weird, dynamic motions with her hands.

"Let me see if there's a message," this strange woman I'd never seen before said to my mom. She told us to close our eyes and then drew in a deep breath.

A bird tweeted.

"Listen to the bird," Rain said, which I thought was rather uninspired. "The bird says, just be. The bird says you're all right." She snapped and snapped again. Then she smiled and exclaimed, "The Council of Twelve! They're here!"

I opened my eyes and looked around. We were sitting on the sunporch, and I was the only one peeking. My mom, me, this interloper. My mom had her eyebrows raised over her closed eyes, as if she were trying to work something out.

"The Council of Twelve says you'll be fine, Marybeth! You'll be fine!"

It's important here to say that health isn't the absence of illness and that illness isn't the absence of health and that people are fine, yes, fine even when they're ill because ultimately everything is fine because either you believe and all the pain and the suffering and the joy and the pleasure and the silliness is a great rushing movement of cosmic beauty, or you don't believe and none of it really means anything, it's just a whirling loop or an eddy that can be described but not really experienced since it's an illusion of matter and motion so it's fine if you get bone cancer or breast cancer or lymphoma and your family watches you die.

But that's not what Rain meant by "You'll be fine!"

My stepfather walked in. That's what my stepfather did throughout all of this, which is why I don't mention him often. He just appeared from time to time; we always saw him when he was walking into the situation. It always began without him. And just a few months after my mother died, he married another woman and disappeared altogether into the house my mom once lived in.

"This is bullshit," he said to us. "I don't feel like paying for this nonsense."

It probably was nonsense.

Either way, a few months later, my mother was dead.

You are going to be blamed by yourself and others. As I write this, I fear that I'm creating a trap for myself, and in that fear is a sort of blame. Maybe if I write about not having cancer, suddenly I'll have it again. We fear illness so much that we think that if we can just not think about it, if we can just not speak of it, we'll avoid it. Silence as treatment. Don't talk about... Don't mention... Don't dwell on....

And who knows? Maybe we should be more careful.

And then I remind myself, no, that's nonsense, bullshit. I treat my thoughts, I check them, I fear them, I discard them.

This dance with your thoughts is what some people would call "superstition." If I agree with these people that it's just superstition, then the world is just a tide of forces. But there's a weird paradoxical snag: If the world is just a tide, a motion, a weight, a pull, and my thoughts aren't related to my health, then what does it matter if I worry or not?

And isn't my health, in at least one way of seeing, entirely composed by my thoughts? When I experience pain or worry, when I feel pleasure—these feelings come from me as much as anything else. I might not always be able to decide how I want to feel about everything, but these feelings are mine, or are humming through me.

There's the familiar image of the happy sick person, dying with a smile, and it's an image of someone who does not appear to be sick at all. There's also the idea that one may be confident during illness. Don't worry, it'll all get better. Is that person sick or well?

Susan Sontag's second cancer was uterine sarcoma.

She wanted treatment, and she got it in the form of chemotherapy, which the doctors said could possibly cause leukemia.

In 2004, Susan Sontag found out she had myelodysplastic syndrome, a condition related to leukemia. Leukemia was her third cancer. This is what Susan Sontag died of. She tried a bone-marrow transplant. It didn't stop the cold differentiation of cells in her blood. It was then that she admitted in a cry that she was going to die. Her son wrote about hearing her cry: "'But this means I'm dying,' she kept saying, flailing her emaciated, abraded arms and pounding the mattress."

We reach out to the hand that promises to pull us to shore. The hand is a blade. The blade cuts into our skin, and the harder we cling, the deeper it cuts. But if we don't hold tight, we'll never make it out of the water and the waves that are drowning us. If we let go, then what?

Three cancers. There was no hope for Susan Sontag, no more treatments left. But perhaps for someone else there would have been. Treatment isn't simply what "works" (if so, the cell transplant wouldn't be treatment at all, nor would my mother's radiation therapy), it's what you choose to see as treatment.

"My mother had utter contempt for complementary medicine," said Susan Sontag's son years later. "I'm putting it politely... I could use other terms."

No acupuncture, no mistletoe shots, no healers. For Susan Sontag, treatment meant an extremity of the Western worldview, its radical margin, even if embracing that extremity would later play a part in killing her. And there's that blame again: She chose a treatment for one cancer that killed her by creating another.

A question that is bound up in illness for us: Who's to blame? If the person who chooses to pray as treatment dies of cancer, is it their fault? If so, isn't the same true for someone who chooses chemotherapy for cancer and dies of cancer?

People will be quick to tell you that some attitudes toward health are "dangerous." This is true. They're all dangerous.

Between two cancers, my mother used a hormone cream to help her have sex more easily. Later, some people in my family suspected that this resurrected the first cancer. I have no thoughts either way about this. My mother was also depressed, she was constantly having dental work done, she didn't exercise often, and she ate a lot of sugar. These are all "reasons" why some people say she might have gotten cancer. Responsibility and its harsh twin, blame, are treatment for anxiety.

But what if we eat raw food? What if we drink enough water, if we take vitamins, if we sleep well, if we exercise, if we meditate, if we go on "retreats," if we take psychedelic plants, if we get massages, if we become vegetarians, if we eat more organ meats, if we force ourselves to laugh, if we take morning walks?

We try to avoid illness and treatment, and in avoiding it create a constant state of illness and treatment.

You're going to do the best you can. The choice of what kind of treatment we want is fundamental to being human. Treatment is a perspective on illness, born out of doing our best with the understanding we have of the world.

Four years after that doctor in Massachusetts told me he thought I had lymphoma, I had sex with a lymphoma and leukemia specialist.

It was a coincidence. Afterward, when we were lying in the dark room, next to but not touching each other, he told me he was a doctor, professor, and researcher. I was lying on my stomach, naked. I told him everything that happened.

"So you never checked again?" he asked.

No. I mean, I'd had a few blood tests. Not directly related to lymphoma, but they probably wouldn't have been so good if I did have cancer. I probably never had it. He put his hand on my lower back.

"No, you probably self-cured."

Self-cured?

"Yeah, it happens all the time, no one understands it really. Someone has cancer and then, you know, they're all better. Self-cure."

I told him about my grandmother. How, decades ago, when she visited from Syria, my parents took her to the doctor. The doctor said she had only months to live, but my grandmother didn't speak English. My mother and father decided not to tell her. I don't know why, or if this is morally right or wrong, they just decided not to say anything. My grandmother lived and lived for decades. It was like she was never going to die. And she didn't die of that disease she never knew she had.

The lymphoma specialist said, "Yeah."

So casually.

Sure, people just cure themselves of cancer without doing much, no big deal, doesn't everyone know that?

I'm not saying do nothing. This isn't about advice, or about what you should do if you're sick. Right now there are people at the exact moment of death. Right now there are people finding out that they are sick, that they may die, but perhaps a treatment, a new treatment, an experimental treatment could save them! And there are people who don't know they're sick and will never know. They'll just live or die, and their loved ones will find out later that there was something tumbling around in their guts or their brains. Or not.

My mother read the language of treatment in her own way: snaps and doctors and envelopes. We took care of her, my sister and I and my older brother and my mother's friends and the hospice nurse. We bathed her and read to her and watched the treatments she chose work in their own way, for a while. She told me she loved me in a haze. Then suddenly my mother couldn't speak. She stumbled over her words, and her mind was forever somewhere else after that.

Susan Sontag, who knows what she stumbled over? She tried to be as sure as she could. Cancers kept happening to her. Treatments kept happening.

Me, I didn't do much. I'm not saying do nothing. Like I said, this isn't about advice. To know that the world is baffling, to know that you're doing the best you can, so you don't have to blame yourself for your choices: I don't have any advice other than that.

I tried to walk away from treatment and I failed. Or I succeeded. I'm not sure. All I know is that I'm still alive, and one day, sooner or later, I won't be.

Treatment might save you, or maybe it doesn't save anyone. ![]()

Conner Habib is a writer, lecturer, and vice president of the Adult Performer Advocacy Committee. His Twitter is @ConnerHabib. He lives in Los Angeles.

This is the first of two essays on illness, cancer, and Susan Sontag. The second essay, by Trisha Ready, will appear next week.