James Baldwin was not a huge fan of American theater. He called it, "commercial... stale, repetitious, and timid." But for years he had an idea that he could not get out of his head. He wanted to write a play based on the tragically short life of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old who was murdered in Mississippi in 1955 after offending a white woman in a grocery store.

As Baldwin recalled almost a decade after Till's death:

I do not know why the case pressed on my mind so hard—but it would not let me go. I absolutely dreaded committing myself to writing a play—there were enough people around already telling me that I couldn't write novels—but I began to see that my fear of the form masked a much deeper fear. The fear was that I would never be able to draw a valid portrait of the murderer.

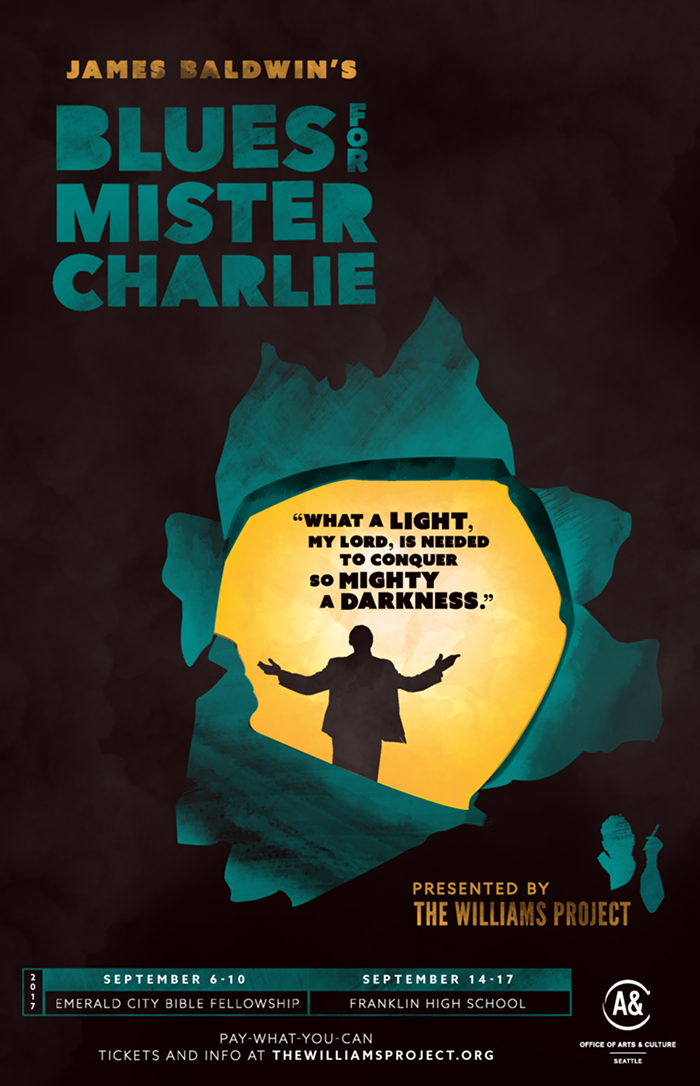

As the Williams Project proves with their new production of Blues for Mister Charlie, Baldwin mastered the challenge, and then some. In doing so, he created a play that's revelatory, compelling, deep, and shocking. It's arguably more shocking in 2017 than it was in 1964, given the nonstop use of the n-word, the then-current attitudes toward women (even the racially enlightened white folks are horribly sexist), and the relatively scant social progress made since then.

Ryan Williams French plays Richard Henry, the character loosely based on Emmett Till, with brazenness, energy, and a winning smile. Richard's confidence and his recently kicked drug habit, which would both be regarded as harmless immaturity in a white man, are interpreted by the white people in his Southern town as oversexed, cocky dangerousness. The mix of charisma and fear French brings to the part is heartbreaking.

Leicester Landon is fantastic as Lyle Britten, the uneducated, repellent white guy accused of his murder. He's one of those characters dead set on his own superiority, blind to his own ignorance, and desperate for power over anyone he can think of as lesser (including his wife, whose naiveté is played brilliantly by Brenda Joyner).

Lyle's close friend and the white editor of the local newspaper, Parnell James, played with sympathy and intelligence by Max Rosenak, tries repeatedly to enlighten Lyle about his prejudices, to little avail. At one point Lyle asks, in language I'm not going to quote directly: Isn't a certain place in town the place where black folks bury their dead?

"When the dogs leave enough to bury, yes," Parnell says.

"Dogs?" Lyle says. (Again, he is not a smart man.)

Parnell replies, "Yes. Dogs. Teeth. Barking. Lots of noise."

Horror ripples through the audience at the thought of a dead people's bodies being treated this way, but nothing like horror shows up on Lyle's face. Parnell has again failed to connect Lyle to his own conscience.

Other standout performances include Rafael Jordan as the Reverend Meridian Henry (Richard's father) and Nancy Moricette as Juanita Harmon (Richard's love interest).

Juanita delivers the most Baldwinesque line of the show when she says, striking a defiant posture on the witness stand: "I am not responsible for your imagination."

The show's director, Ryan Guzzo Purcell, has added a choir that's not in the text of the script—a choir whose voices transcend the heaviness of the show, and transform the room. (Seriously, go for the choir alone—they are amazing.)

The Williams Project's purpose is to "make theatrical excellence accessible" to economically diverse audiences "while paying artists a living wage." Using non-traditional venues helps them pull that off. I saw Blues for Mister Charlie at Emerald City Bible Fellowship, a church in the Rainier Valley, and something about the venue being an actual church, and not a theater, added rather than detracted from the effect. The simplicity of the room, its humble everydayness and lack of flash, underscored and emphasized the actors' powerful performances.

This coming weekend, Blues for Mister Charlie moves to Franklin High School, running Thursday through Sunday.

These are professional actors, and world-class singers, using simple materials and pure talent to make a profound play by one of the greatest American writers of all time. Go see it.