Given that I’m a pediatrician, you might expect this opinion piece to be about the coronavirus pandemic. It’s not. I’m here to talk about the weather. With everyone celebrating the long-awaited rainy deluge this past weekend, I’m worried that we’ll quickly put last summer in the rear-view mirror.

This was my first summer practicing medicine in the Pacific Northwest. I had girded myself for COVID, along with the usual ailments, from allergies to broken bones. But this year, with heat waves coupled with smoky skies, the hospital where I work saw a significant increase in heat- and smoke-related ailments. I wasn’t expecting that.

June 28 will stick with me forever. Over 1,000 people landed in emergency rooms across the region with heat-related illness when temperatures reached an unprecedented 108 degrees. Over 100 Washingtonians died as a result of that first record-breaking heat wave of the summer. It’s the deadliest weather event in Washington’s recorded history.

The health impacts of climate change are not routinely taught in medical school, nor are the health impacts of bad climate policy. After this summer, however, it's impossible for doctors not to recognize climate as a public health crisis and make that connection at the patient level and at the policy level. As we head into the rainy season, we need to remind ourselves that this past summer of extreme heat may not be a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly.

While there is no silver bullet to prevent climate change-driven illness and death, much to my surprise, homes and buildings turn out to be both a problem source and an opportunity for solutions.

Homes and commercial buildings are the fastest growing source of climate-altering pollution in Washington state, putting more greenhouse gases into the air in some of our cities than cars. They are responsible for over a quarter of our state’s air pollution. That’s because most of the appliances we use inside buildings run on gas, which releases carbon pollution when burned. Most of our gas also comes from fracking, which frequently releases methane – a highly potent greenhouse gas that leaks when it is extracted and transported through miles of pipelines.

Gas stoves, furnaces, and water heaters also release pollutants that can harm health, which is both a professional and a personal concern for me as a parent of young children. These pollutants that enter the air in homes and neighborhoods include nitrogen dioxide, particulates, carbon monoxide and formaldehyde, all of which can be harmful, especially to kids. Children living in a home with a gas stove have a 42 percent increased risk of experiencing asthma symptoms and a 24 percent higher risk of developing asthma in their lives. The indoor pollution impacts from stoves are worse in smaller, less-ventilated homes, which are often lower-income households. The pollutants from furnaces and water heaters that vent outside add to outdoor air quality problems that also disproportionately affect lower-income households and communities of color.

The good news is that we already have the technology to transition our buildings off gas and onto Washington’s increasingly clean electricity grid, and it will even save us money in the long run. In fact, building electrification is the cheapest way to reach the state’s climate goals. Even better news: we’re not Texas! I came to Seattle from Texas and, believe me, energy policy is a disaster there, thanks to the industry’s grip on elected officials. Climate change is a nonstarter for Texas’ professional medical associations, which makes me even more grateful to be practicing medicine in a city and state with forward-looking, climate-sensitive policies.

So far, we have been successful in fending off fossil fuel industry lobbyists who have been trying to strip Washington cities of their ability to strengthen building codes at the local level. This is part of an orchestrated nationwide industry response to cities around the country that are ensuring new buildings are fossil fuel-free. Tying the hands of city leaders eager to reduce emissions will only make our collective job harder.

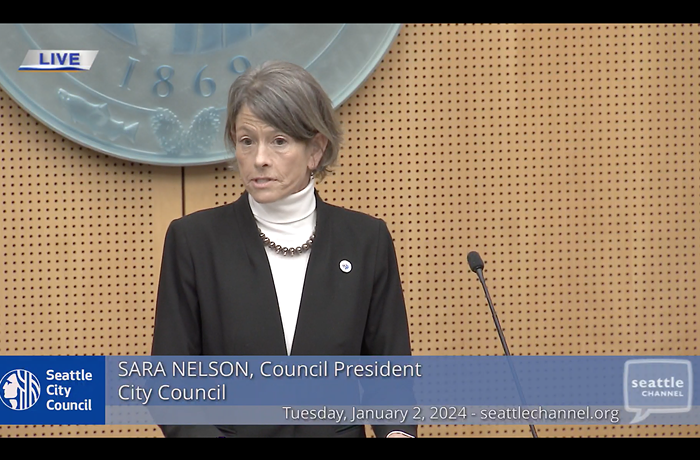

Seattle is already leading the way, requiring electric heating and cooling in new commercial and large multi-family buildings, but to be successful we need state- and federal-level policy solutions that work for everyone – homeowners, renters, and business owners alike. Strong state energy codes, financial support to help people afford upgrades, and meaningful utility incentives are key.

This summer, my hospital and too many others have been pushed to the breaking point as we jumped from COVID to extreme weather crises and back again, trying desperately just to keep people alive. We need to start treating climate change like the public health emergency it is by reducing fossil fuel pollution and investing in safer, cleaner homes. Our lives depend on it.

Dr. Mary Beth Bennett is a pediatrician in Seattle and a member of the Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility’s Climate & Health Task Force.