"This is my office," Dean Wong told me, flopping down on the corner stool at the bar of Tai Tung restaurant, where the owner called out greetings, and where a sign on the wall proclaims it the oldest remaining Chinese restaurant in Seattle. Wong grew up in a storefront down the street.

We were meeting because I saw Wong's photographs in two exhibitions and a new hardcover book called Seeing the Light: Four Decades in Chinatown.

If Chinatown is a character whose many identities unfold over a lifetime, Wong is their most devoted portraitist. He's one of those artists driven by a singular subject.

"I have this immense curiosity for this place called Chinatown," he told me. At 61, he acts the student, not the expert. He goes out to shoot every weekend.

I asked him to talk about his book and his exhibitions, and to share his streets and alleys, so we set out on two extensive walks this summer. He carried an iPad loaded with thousands of his pictures.

We hit the hardest places first. It has been a bad year.

Wong's youthful wife, Jan, died of disease. His best friend, Donnie Chin, was shot and killed in a case that's still not solved. For a while, Wong "didn't want to be here anymore."

Wong took me to Chin's two makeshift memorials, where there are photographs by Wong, paper cranes, handwritten notes of remembrance.

Chin was sort of like Batman for Seattle's Chinatown-International District.

Chin and Wong cofounded the International District Emergency Center in 1968, and Chin was its leader until the moment of his death, responding to emergencies at all hours before paramedics or police even arrived.

"He is our angel in a ghetto package," Wong said at Chin's memorial, which I watched later on video. The Seattle Times ran a photograph of the Seattle Fire Department extending and crossing the ladders on a fire truck, a ceremony usually reserved for one of their own.

Standing in front of his memorial, Wong told me that when Chin was going on vacation, he'd call the nonemergency dispatch number and say, "This is International District," and give them his return date. (A police spokesman couldn't positively confirm this story but had heard the same thing.) "I said 'motherfucker' at the memorial," Wong told me, looking at a large photo of Chin in the alley, sitting watch. "It's what Donnie would have said."

When they started IDEC, they wore orange and red jumpsuits and the police eyed the two young guys "with long-ass hair down to our shoulders."

Today, Wong's hair is shorter. He's still got the mustache and scruffy sideburns, now salt-and-pepper. He wears a gold chain, orange sneakers, and a rotating array of drugstore sunglasses. He comes across as a gruff and gritty sweetheart.

The first time I met him, he was wearing a shirt he had printed special. It boasts: "Made in Chinatown U.S.A."

When I asked him about it, he told me sometimes when people see his photographs, they compliment him and ask him when he's going back to China to take more. To which he blurts, "I've never been to Asia!"

"Do I want to go stand on the Great Wall of China? Sure, maybe someday," he told me. "But I want to go to all the Chinatowns in the US, and maybe that's more important."

It would seem so. Seeing the Light includes photos and stories from Chinatowns in San Francisco, Vancouver, BC, and New York as well as Seattle, where he was a photographer and reporter at the International Examiner. He's traveled also to Los Angeles and Oakland but hasn't been able to afford to see other Chinatowns. Portland has a Chinatown in decline, so active partisans are starting a small museum, and Wong is the first scheduled artist there in the spring.

"If you google 'Chinatowns in decline,' you'll get a whole bunch of stuff," Wong told me, and later I did, and it was worse than I'd thought. First hit: "The Slow Decline of Chinatowns" (BBC). Next: "The End of Chinatown" (the Atlantic), "Mapping the Alarming Decline of America's Chinatowns" (Wired).

Also on Wong's mind last week: an alarming e-mail sent to supporters by the Wing Luke Museum, the cultural heart of Chinatown-International District, which holds many of Wong's photographs documenting the neighborhood.

The museum cited the encampment under the nearby freeway (since removed) and "the recent loss of the neighborhood's beloved protector Donnie Chin" as reasons why "in July the Museum board came close to closing down operations."

The Wing Luke is back at full confidence but in need of visitors and love, the museum stressed to me in a phone interview.

If Chin was Chinatown's protector, Wong is its interpreter, and Wong's interpretation is that the kernel of Seattle's Chinatown is intact. In its e-mail, the museum described the neighborhood's "vulnerability," but to Wong that's part of its DNA as a place originally created out of need.

He walked me to a concrete basketball court. "We never had grass," he said. "Never." What they always had: cockroaches that Wong suspects are still there. "People are living like shit up there," he said, and yet poverty in Chinatown has been the other side of the coin of solidarity, of being a community that sticks together, he said.

He was present in the late 1960s and early 1970s at the founding of many of the grassroots aid organizations, like IDEC, that he said are the reliable safety nets that have prevented fates like Portland's from happening here.

"This Chinatown's doing good," he said. "There's a lot of Chinatown left."

As an artist statement, that would be a little one-note: I'm just here "Seeing the Light." But Wong's photographs are not PR. Individual pictures can be stunningly plain, almost neutral, embodying the hesitations, courtesies, and contradictions of a documentarian painfully aware that his pictures are also self-portraits. These are high-stakes shots for Wong, who so thoroughly identifies with them.

But he pulls it off. The Chinatown that develops cumulatively across the span of his pictures is steadfast and enigmatic, a public place that's also private, where men, women, and children go about their everyday lives navigating individual dramas and layered public identities. That could be said of anywhere. It's universal, and he captures it in specifics.

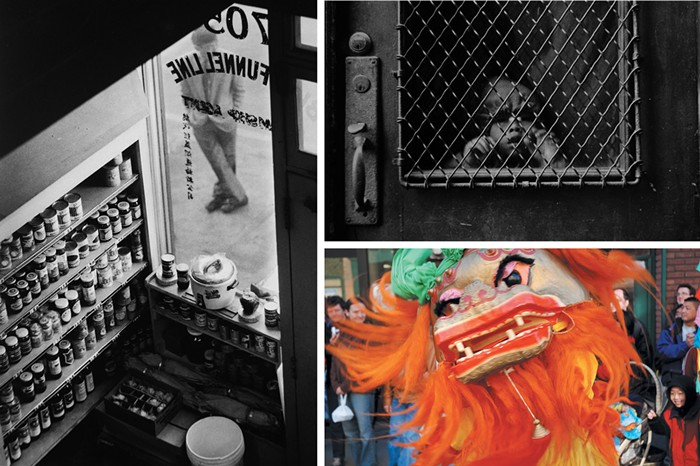

On the street, Wong's style is to blend in, to wait for moments and not get too close. Stories are implied in small details. An older man near a doorway is eclipsed by a younger man with a spangly costume thrust over his head in a parade going by, but it's the older man who is in focus, undistracted by the younger man's wild exertions of tradition.

In another picture, an old nisei woman's hands press down a little too hard on her lap as she poses for the camera while Cary Grant plays on the TV next to her. Is she wondering what this younger Chinese American photographer wants with her and Cary Grant?

Without appearing in his pictures, Wong doesn't try to cut himself out of them.

But what I discovered this summer is that Seeing the Light only scratches the surface of Wong's vision. As we wandered the streets, I kept gasping at his discoveries, seen on iPad. They need culling, arranging. There is a large exhibition here.

One of his folders contains a portrait of the interiors of the former Louisa Hotel. The building nearly burned down a few years ago. Wong went in afterward and excavated hidden murals of old Seattle among the ruins, the equivalent of cave art for a young city. Those present according to what Wong found included sailors from the USS Medusa, Chinese immigrants longing for a bucolic home, and African Americans in jazzy top hats and furs.

Wong said his father, a restaurateur and gambler with a reputation as an enforcer, probably hung out at the gambling den in the Louisa. His father died when Wong was in the fifth grade, and he never explained giving his young son what was an extravagant present for a large working-class family: his first camera. Wong always assumed his father won it in a game, by chance. Maybe he got it at the Louisa. ![]()