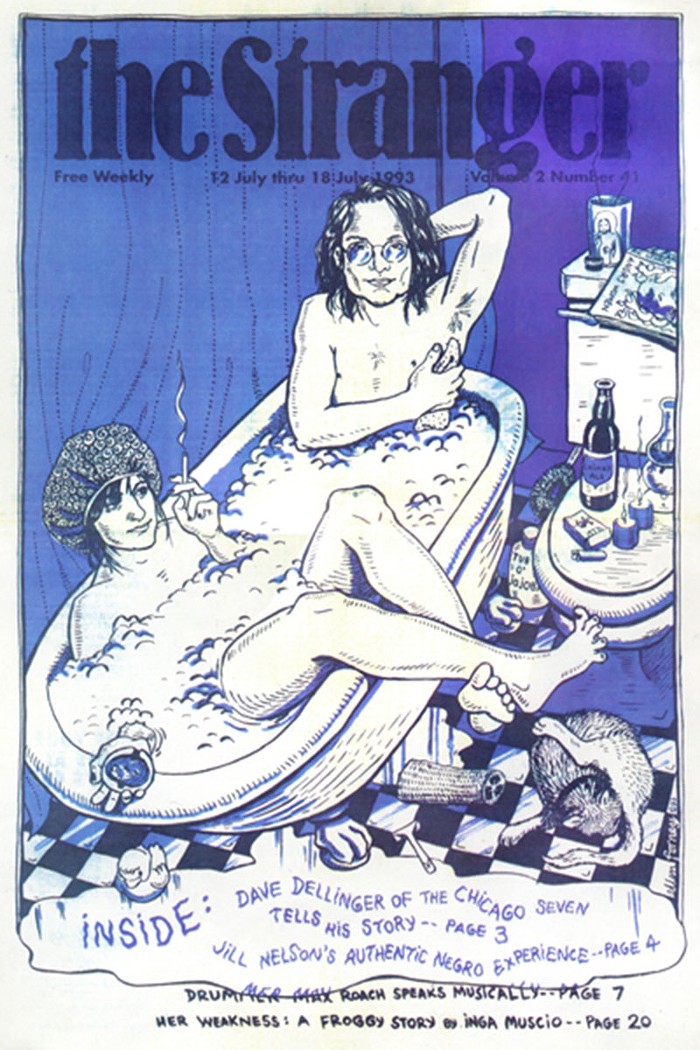

Ellen Forney's first Stranger cover was also her first big break. It was 1993.

Ellen Forney's first Stranger cover was also her first big break. It was 1993.

Using a brush on thick bristol paper, she painted a portrait of relaxation, liberation, and cool: two friends chilling and smoking in the bubble bath next to the cat licking its butt.

Carefully, she carried the painting to the upstairs of the Wallingford house acting as the "office" of the paper. Gingerly, she handed her fragile, proud creation to James Sturm, now an acclaimed artist whose work adorns the New Yorker, who was then the first art director of the paper.

Making fun, he bobbled her art from hand to hand, joking that he would drop it. Except then he did drop it. And on its way down, trying to get it, he accidentally kicked it.

It was the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

Forney, as well as countless other artists, has commandeered the cover of The Stranger many times. Every week, The Stranger picks a work of art. The Stranger puts that work of art on 66,500 pieces of paper and distributes those papers to 2,100 locations—to every corner, counter, and cafe in the city.

It is a cumulative group art exhibition larger than many museums could ever show.

For that week, the artist sees her work everywhere she turns. "And I love it even in the gutter," Forney, who is now a teacher and the author of a celebrated graphic novel, told me when I asked her how it felt.

I don't know of any other weekly newspapers in major American cities that do their covers this way. They prefer to illustrate what's inside with a topical graphic or a news photograph. The Stranger's cover has nothing directly to do with what's inside. It might echo a tone of voice, or the mood of a subject, but that's all. It represents itself, and art itself. (There are a few exceptions, but this is the general rule.)

It's always been my take, as the paper's art critic, that the point is not to judge individual covers but to consider the cover as a free surprise gift every week. As I write this, I have no idea what will be on the cover of the paper you're now reading.

The Stranger also remains the only weekly newspaper in the nation to employ a full-time staff art critic (hi), and the only paper I know of that gives out $5,000 each year, no strings attached, to a local visual artist in the annual Stranger Genius Awards.

Why does it do all these art-related things? There is one beautifully simple and undemocratic reason: because publisher and cofounder Tim Keck thinks it's important.

A fan of old newspapers and magazines, Keck once brought huge stacks of his dead grandfather's The Ring boxing magazine (Keck's grandfather was a boxer, so that tells you something about how Keck perseveres in the news business) to the offices of the Onion, the satirical publication that Keck also cofounded.

Keck had loved Joseph Pulitzer's the World, which at the turn of the 20th century was the most beautiful newspaper around, with hand-lettered headlines that curled like party ribbons and huge full-color drawings and halftone photographs of automobiles and orcas and Mark Twain's face pushing aside gray seas of text on the front page like luxury ocean liners.

At The Stranger, Keck wanted to "paint the city with artists," he told me, plus "we were playing the opposite game." It helped that nobody else in weekly newspapering published stand-alone art out front. Graphics and news photos are hard to make interesting every week without a budget, anyway, and artists want their work seen.

The first cover was creepy. It was a black-and-white drawing of a woman emerging from a dark forest with a man slack in her arms. Facing them was a mirror couple, genders reversed. These were the days when everything was meta. One of the women held The Stranger, its cover a miniature of the actual cover, as if the paper had also come out in a different universe, somewhere weirder. A toddler with an ancient face grimaced at the reader and pointed to the forest.

"I was probably just discovering Dan Clowes and wanted to do something creepy and alternative," Sturm told me. "I'm a little embarrassed of it now."

Sturm is a household name in comics today, but as the first art director of The Stranger, he was a fresh grad of the School of Visual Arts in New York with his first Fantagraphics book coming out. He brought connections that established the early Stranger as a bastion of alt-comics with covers by heroes like Peter Bagge, Chris Ware, Roberta Gregory, Pat Moriarity, Jim Blanchard, and Jim Woodring.

Jason Lutes, another in that line, was art director after Sturm, followed by Dale Yarger of Fantagraphics, who continued the experimental comics style. Stand-alone comics inside the paper were a hallmark, too. They told stories—how to have anal sex, by Dan Savage and James Sturm, 1992!—that were sometimes pointed and sometimes entire universes of their own, excerpts from forthcoming books or works that would eventually be compiled into books. The Stranger was a comics engine.

Over time, the cover imagery broadened to include vintage collages, the art of the "lowbrow" movement, and contemporary photography, painting, and drawing under art directors Joe Newton, Corianton Hale, Aaron Huffman, interim Mike Force, and, today, Tracie Louck (the first woman).

I have my favorites. There's a Venn diagram detailing all the possible crossovers between people who sing, dance, and steal things by the funny, shaky-handed drawer David Shrigley, commissioned by Hale ("One of the best things about the paper was writing to my heroes and having them actually write me back," Hale told me).

On November 11, 2004, The Stranger coached Seattle through the devastating reelection of George W. Bush with a cover that became a collector's item. After the election results were in, editor Dan Savage typed up a quick manifesto and e-mailed it to Hale. Hale designed the phrases in a stack of colored arrows that began, in huge type across the top, "DO NOT DESPAIR." We no longer had to think of ourselves as citizens of the United States, Savage wrote. We were citizens of the United Cities of America now, a place where John Kerry took 61 percent of the vote.

No exhibition of the art of American progressivism would be complete without this cover.

On March 30, 2006, also under Hale and following an idea from then-editor Christopher Frizzelle, The Stranger removed all text from the cover except the whited-out masthead at the top of a wall of robin's-egg blue, the dreamy blue of children's rooms. The wall was interrupted by horizontal lines, like a piece of notebook paper enlarged. It was a completely abstract cover, with no words. But that was the week when a man opened fire at a party and killed six people inside a sweet blue house on Capitol Hill. (Jimmy Clarke went to the house and took the photograph.) The cover reminded me of the way Maya Lin's Vietnam Veterans Memorial in DC reflects the blue sky on a sunny day, abstract, terrible, and peaceful at the same time.

"Nutty but ambitious" is how Sturm described the early Stranger's visual philosophy. Built into The Stranger's DNA are subtly enraged humorists and absurdists like David Schmader (Savage and Schmader were behind the cover when The Stranger dressed children in the actually scary Halloween costumes reenacting Abu Ghraib) and Kelly O, whose flamboyant and eternally off-kilter photography is a completely stealthy critique of pretension, wealth, and power.

You could do worse than "nutty and ambitious" in choosing two adjectives to describe Keck, the publisher. For instance, he invented the masthead. Those plump, almost silly, yet somehow noble letters that form the words The Stranger have never changed.

Keck got them in 1991 at the grocery store, the Food Giant that became QFC, specifically. As an outsider, he was struck by the store's generic brand—Western Family, with its "fake corporate homeyness"—so he disguised his outsider newspaper as the generic brand and also called it "America's Hometown Newspaper."

He lifted the Western Family font right off a can. A can of what, he does not remember.![]()