The first inquest hearings in over a year will commence next month as King County restarts the process of publicly investigating instances where police have killed people while in the line of duty. County Executive Dow Constantine halted the inquest hearings, a form of public fact-finding tribunals, last year to reform the process. Constantine said at a news conference on Thursday that the reformed hearings are a nationwide model for confronting instances of deadly police violence.

“We are certainly among the few jurisdictions [in the country] that have adopted a process that is this transparent and can seek to identify what can be done to prevent law enforcement-involved deaths in the future,” Constantine said Thursday.

The first tribunal, which the county officially calls inquest hearings, will concern the death of Damarius D. Butts, a 19-year-old black man who was killed by Seattle Police Department (SPD) cops during an armed standoff downtown over two years ago. Robert McBeth, one of the new administrators of the inquest hearings, said Thursday that the first pre-hearing conference meeting in the Butts case will take place in the next two weeks. McBeth did not give hearing dates for any of the more than a dozen other instances in the last two years of cops killing people, including not addressing when the high-profile Charleena Lyles inquest hearing would proceed. Lyles, a pregnant black woman, was killed by two SPD cops in her North Seattle apartment in June of 2017.

Inquest hearings are not trials—they do not hand out any criminal charges or civil settlements. Instead, they seek to establish the facts surrounding a death at the hands of law enforcement. Constantine put the hearings on hold in January of 2018 after community advocates complained that the inquest hearings were slanted in favor of clearing cops of any wrongdoing. The new inquest hearing process makes several key changes, most notably expanding the scope of the hearings to include if police followed their training and if their training should be changed.

Constantine’s reform also included hiring dedicated staff for administering the hearings. Before, the hearings were administered by the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office and overseen by a King County Superior Court judge. The hearings now have their own staff to coordinate the hearings, a staff attorney will assist the proceedings of the trial, and a rotating list of retired judges will serve as the “administrators” of the hearings.

Robert McBeth, one of the retired judges who is acting as an administrator, declined to comment on Thursday about how long it will take the county to work through the backlog of cop shootings that still need inquest hearings. Constantine’s office supplied reporters with a list of 12 names that need inquest hearings but advocates have questioned that list. My count shows up to 16 names that still need hearings.

While the hearings are not trials, the information uncovered in them can be used in future civil and criminal cases. The county’s prosecuting attorney waits to decide if they want to seek criminal charges against a cop who kills until after the inquest hearing. Larson confirmed after Thursday’s press conference that his office reviews the facts presented in the hearings before deciding if they want to file criminal charges against officers who kill someone.

Constantine said Thursday he called for inquest hearing reform in response to an apparent increase in the frequency of cop killings. Constantine said the number of inquest hearings increased from two in 2015, to seven in 2016, to 13 in 2017.

“That is what really made us want to know not just what happened in that moment but also what could be changed institutionally so we would not have this kind of pattern continue into the future and have fewer fatal interactions between police and civilians,” Constantine said.

More Transparency

When Constantine set out to reform the inquest hearing process last year he convened a group of both members of law enforcement, police reform advocates, and families of people killed by officers. He said Thursday that he took many of their recommendations into the new law.

“Ultimately, the coalition and law enforcement were not able to reach a final agreement but my executive order embraced a lot of the ideas that emerged during that process,” Constantine said.

The reforms updated the inquest policy in several key ways:

• Hearings will be recorded and shared online,

• families of the deceased are provided legal counsel,

• the cops involved no longer need to be present during the hearings, but the chief of police or head of their law-enforcement agency is required to be present,

• attorneys for the family can now make opening and closing statements and call their own expert witnesses, and

• the scope of the hearings will expand to ask not only the facts of the case but also whether changing law-enforcement policies could have prevented the death.

McBeth declined to say Thursday how quickly the hearings will be posted online or if they will allow reporters to record audio of the hearings. Previously, judges would frequently bar the public from streaming video of the hearings and stop reporters from even recording the audio of the hearings. I covered the Che Taylor inquest in 2017 and Superior Court Judge Garrow blocked all audio recordings of the hearings, which seemed intentionally designed to limit the transparency of the hearings. It’s hard to understand why audio recording should be barred during a public hearing dedicated to transparency.

SPD Might Further Delay Inquests

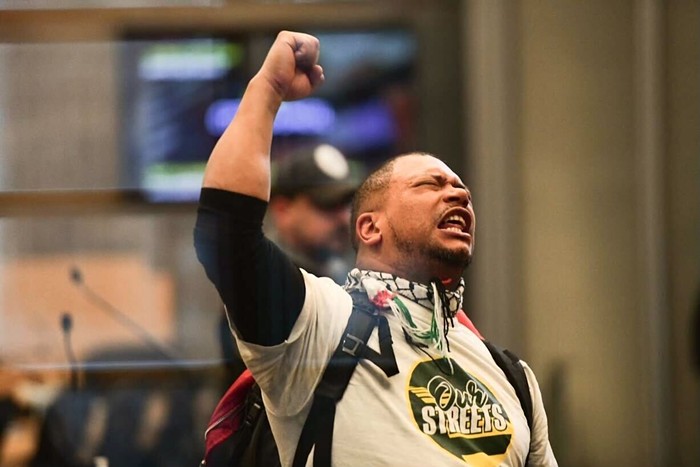

Thursday’s announcement was mostly attended by members of the media but members of at least one family preparing for an inquest hearing were in attendance. Katrina Johnson, the cousin of Charleena Lyles, attended the announcement and said afterward that she was happy with the reforms.

“We appreciate the changes that have been put in place,” Johnson said. “I think we have a better inquest process than we did before these changes were put into place.”

But Johnson added that she and her family are growing increasingly concerned that their inquest hearing might be further delayed because of the SPD. The family is trying to build their inquest hearing case with documents related to police training, but SPD has refused to release those documents, according to Corey Guilmette, an attorney that is representing the Lyles family.

“The city of Seattle has taken the position that they will not turn over any additional information to the family despite numerous requests,” Guilmette said.

Guilmette, who also represented Che Taylor's family during their inquest hearing in 2017, said the city is waiting until an inquest hearing is called before they will release more of the request information, but Guilmette said they are worried that will cause even further delays because the amount of information they are requesting could amount to over a thousand pages of documents. It could take weeks or months to hand that information over. Johnson said the city should not further delay the inquest considering Lyles was killed nearly two years ago.

“That’s my concern that we are going to be waiting for a really long time and we have already waited patiently for a long time,” Johnson said. “It’s unacceptable to continue to make families wait. It’s disheartening to continue to ask for something that you have within your grasp to give to us, and it just further makes me frustrated and angry.”