The great black American writer Ta-Nehisi Coates turns out not to be a great novelist. And this isn't a bad thing. It happens. We can't be good at everything.

Coates, the celebrated essayist who is often compared to James Baldwin, clearly thought that, like Baldwin, he could write fiction as gripping as his nonfiction. He tried, he gave it a decade of his life, but he definitely failed.

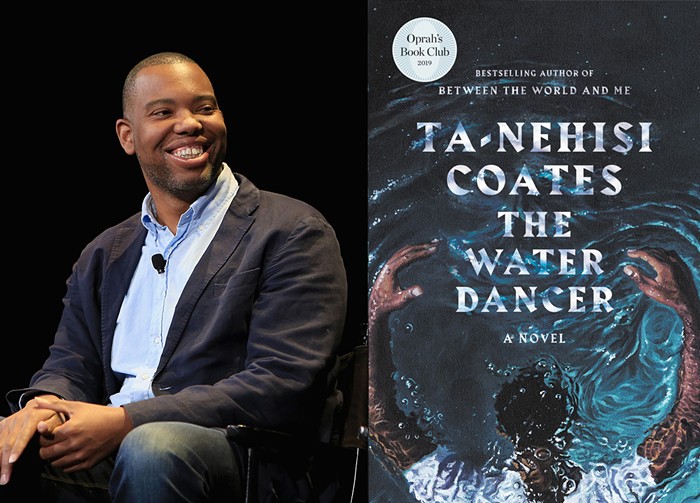

Yes, the novel, The Water Dancer, was picked by Oprah Winfrey for her much-prized book club, and it has received rave reviews in a number of places, but the truth is it's pretty much a mess from beginning to end.

I wanted the novel to be great, because Coates is not supposed to fail. He is on the right side of the fight, the right side of history. The argument he presented for reparations for black Americans in 2014 in the Atlantic is impeccable. His memoir Between the World and Me is a 21st-century masterpiece of American literature. How can this writer do anything wrong?

Well, this is how. The main flaw with the novel The Water Dancer is Coates wrote it to sound and feel like a novel. The story—which is set in Virginia, and is narrated by a young man, Hiram Walker, who has a photographic memory (one of the two superpowers he possesses)—is told with the deliberate gravity of a writer who believes he's writing a major work of fiction.

It's as if Coates did not want the reader to be uncertain about the status of the work. It's not an essay, nor a historical document; it's a serious American novel. Page after page, the language insists on this. That villain has "deep set eyes." This man is looking with "sidelong glances." The room is "flooded with light." There is in the distance "the last orange breath of a dying sun."

The only "respite" from this stiff, stilted, novelistic language is when Coates switches to his essayist mode and describes (in a monologue, of which there are too many in this book, or in exposition) an aspect of American slavery that clearly throws light on an aspect of the culture of our times. Or when Coates describes the narrator's superpowers, which include "conduction," the ability to collapse time and make quantum leaps. (Hiram shares this superpower with Harriet Tubman.)

When I completed this book, which is too long and often too slow, I found a real appreciation for Colson Whitehead's 2016 novel The Underground Railroad. Now that book, which covers almost the exact same ground as The Water Dancer, is a novel that does not sound like it's trying to be important. It gets out of its own way. It has real narrative force. The pages move on their own. While reading The Water Dancer, I could feel my hand turning every one of its 400 or so pages.

Also, Whitehead is much more masterful when dealing with his novel's fantastic element—the underground railroad that is really an underground railroad. Colson's fantasy has the right combination of being very true and very ridiculous at once. In The Water Dancer, the fantastic element (conduction, which is connected, in a very complicated way, to Hiram's photographic memory) always feels like it should be in another book (a comic book), one without the ambition of being a Great American Novel.