Well, Karuna Long is nothing if not resilient.

Since buying Oliver’s Twist, a neighborhoody Phinney Ridge cocktail spot, in 2017, he and his crew have faced a string of setbacks that would have knocked just about any other new restaurant owner out for the count.

First, it was COVID tribulations, like everyone else in the restaurant industry, and the resultant staffing issues, like everyone. Then he got pushback from some in Phinney Ridge for his sidewalk seating, along with major grief for requiring vax cards after other restaurants had dropped the restriction. Amid long closures and inconsistent hours, he stayed in the game.

But the biggest issue with Oliver’s Twist, since the very start, has been the kitchen.

“It’s smaller than a food truck kitchen!” Karuna laughs. “I know I always say this, but it literally is!” When he bought the restaurant, the only food that cocktail-focused Oliver’s Twist served was bar snacks, e.g., truffled popcorn and cheesy flatbreads. So when Karuna and his crew decided to add his mom’s Cambodian recipes after seeing immense success as a popup in 2018, there was still only so much they could do with their flatbread-sized kitchen.

Sure enough, the redux cleaned up. “We did great,” Karuna recalls. “With the dining room closed, it was fine! We had portable burners on each counter. Plenty of space.” But since Oliver’s Twist has reopened for dine-in, they’re back to the original problem: a postage stamp of a kitchen, and ergo, a much smaller menu than Karuna would prefer.

This impacts the staffing situation too. Karuna’s had no trouble finding applicants to cook, but their tune invariably changes when they come in. "They’ll all say something similar to ‘Please keep me in mind when you get a bigger kitchen.’ So, hey, that’s what we have to do.”

Easier said than done, and again, Karuna’s had to employ his creativity and resilience to move forward.

The first plan was to expand into the empty slot next to Oliver’s Twist, formerly Johnson & Johnson Antiques, and build out a full kitchen from scratch. A Kickstarter campaign was launched to help fund the project, but the campaign took forever to get approved, the Kickstarter platform was a struggle to work with, and it was an all-or-nothing model, so they didn’t get a dime if they didn’t make the goal. Then, the space itself turned out to be a bust too. “Would’ve been so perfect to have the space right next door,” Karuna says, “but after working with a design team, it just isn’t gonna pan out.”

So the Oliver’s Twist team is creatively pivoting. The new plan is to take over the former Martino’s space, four blocks north on Greenwood Avenue North, with its gorgeous open kitchen—and start a whole second restaurant, leaving Oliver’s Twist to shine as the cocktail bar it was designed to be. Everyone’s Kickstarter donations were refunded, and now Karuna’s starting anew with a new website, an indie fundraising campaign, and a fresh gleam in his eye.

“Even if we don’t meet our goal,” he tells me cheerfully, “I think of the resilience I learned from my parents. I know we’ll find a way to make it work!”

***

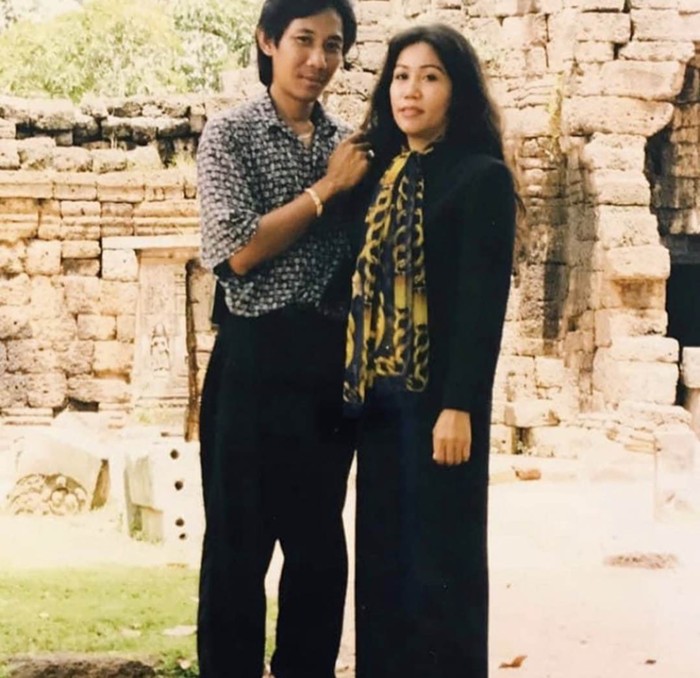

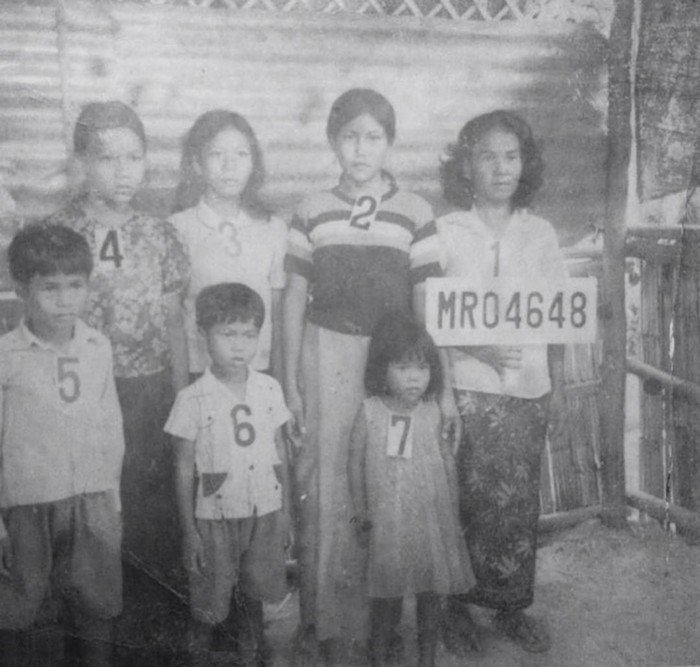

Karuna was born in Seattle’s Mt. Baker neighborhood, the child of a dancer and a working musician both from Battambang, Cambodia’s third-largest city. After surviving the four-year dictatorship of Pol Pot that saw the murder of nearly 25% of Cambodia’s population, first via a bloody civil war and then the even bloodier rule of the Khmer Rouge, Sophon Long and Vichan Chea joined family members in the US, becoming Kimberly Long and Richard Chea. After Karuna was born in Seattle, they bopped around the country, throughout suburban Boston and Atlanta, eventually settling in the Long Beach area of L.A.

"When I moved back to Seattle in 2010,” Karuna says, “after coming up to visit every other summer… it was the best decision I ever made in my life. I really found myself here, thanks to my family.”

Karuna says he gets his can-do attitude from his mom. “My brothers and I witnessed her resilience as she took on her new life in the US, watching her transfer all these survival skills she’d learned as the eldest of seven siblings in Srok Khmer—which Americans call Cambodia.”

The civil war, the widespread famine it caused, and the holocaust that followed forced many Khmer people to reinvent their traditional recipes in times of scarcity—a skill that Kimberly utilized later in 1980s Los Angeles, where not every ingredient she needed was always available. In this way, Kimberly began a fusion cuisine of her own, swapping in local meats and produce and creating Khmer-based dishes that were uniquely hers and passing them along to her sons as she taught them to cook.

There’s just not enough kitchen room to cook them all for us. Yet.

***

As it stands, tiny baby kitchen and all, Oliver’s Twist still has a pretty compelling menu, both the legacy section and the Khmer section! The curry (kar-i) vermicelli noodles, available with tofu or chicken, and the hot and sour beef stew (samlar machu kroeung sach ko) are obvious standouts—and honestly, the white-people grilled cheese sando is bomb as all hell, served on Macrina como bread with giant frico edges, lookin’ like a stained cheese window. Both halves of the menu are notably studded with vegetarian and vegan dishes, featuring jackfruit and taro, and everything appears at your table heaped with a colorful riot of cucumbers and fresh basil and pickled carrots and radishes and so on.

View this post on Instagram

“Yeah, in Cambodia, there are way more vegetarian and vegan options,” Karuna comments, “and keeping things veggie and vegan in this mini-kitchen has been tough. That’ll be huge for us, to be able to offer more of a vegan and vegetarian-friendly menu.”

Although I’m thrilled with all the veggie dishes, I’m personally infatuated with the innocuously named “braised pork bowl,” or kha sach chrouk in Khmer. Here, it’s done with pork belly, sauteed bamboo shoots, coconut milk, and bird’s eye chili over jasmine rice with a flawless jammy fried egg on top.

It’s everything you want from pork belly: the meat itself is so tender it’s heartbreaking, with that barely contained, bacony crystallized fat that’s quick to dissolve in your mouth. Then it’s got this delirious-making soy sauce/star anise glaze with a dash of sweet Cambodian fish sauce, thuk threy, and a little note of cinnamon that rides high in your nostrils. For a week after I first got the braised pork bowl, it was the very first thing that popped into my mind every morning when I woke up. A life-changing dish.

(Fun fact: I'm told the fried egg is actually an American modification to an old Khmer dish—traditionally, kha sach chrouk includes hard-boiled duck eggs, not fried hen eggs. Folks around here reportedly find it more appetizing this way, not to mention easier to eat.)

Also on the current Oliver’s Twist menu, the twa ko, a fermented brisket sausage, is something really special. They grind it and ferment it in-house, and the texture’s not what you’d expect if you grew up eating Western sausages. This one’s highly pixelated, made of minced beef brisket, jasmine rice, garlic, and galangal in a rough natural casing, with big bits of rendered fat and a sweet grilled-on sauce reminiscent of char siu. Twa ko seems to appear and disappear from the OT menu in different permutations, and sometimes it cameos on a charcuterie board with a radiant halo of cucumbers and green onions and basil and carrots and pickles around it—my favorite incarnation of the dish.

***

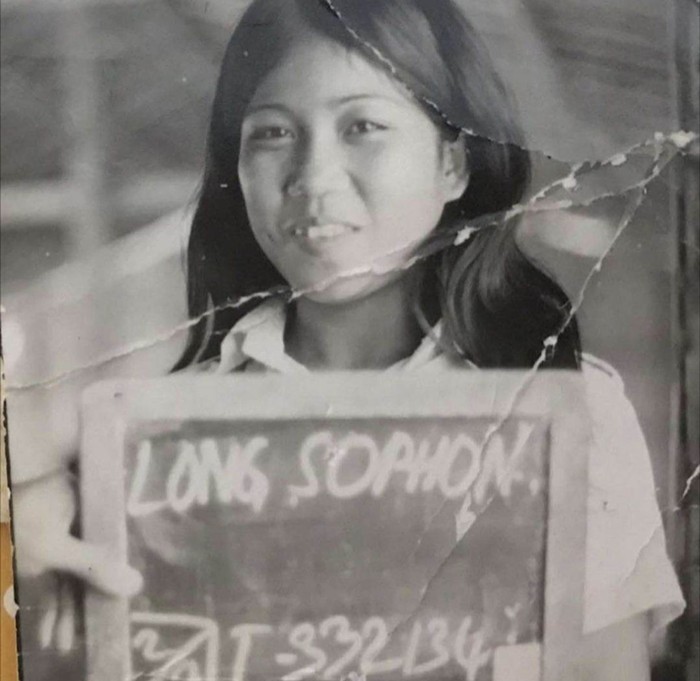

Okay. So. Seattle’s newest Cambodian restaurant, Sophon, is slated to land just up the road, ideally in the summer of 2023. The plan is set.

“Of course, I’m naming the new restaurant after my mom!” Karuna exclaims. “It’s perfect because in Khmer, the word sophon means ‘beauty.’ Our mom embodies that and so much more—she’s a songstress, a classical Khmer ballet dancer, a mom, a nurturer, a healer… She is beauty!” Karuna pronounces her name with a silent H, by the way, if you too wish to pronounce Sophon beautifully.

Karuna’s a dreamer, he tells me—this is already obvious when he’s fresh off a culinary research trip to Cambodia, and it’s a straight-up joy to hear him speak about what he has in mind for Sophon. When asked to name some dishes he’ll be able to offer once he has this magnificent new kitchen, he waxes deliciously.

“Okay! Well, we’re excited to do a play on a traditional dish called pleauh sach ko. It’s essentially a ceviche with thinly sliced lemongrass, bright julienned herbs, and a little umami from fresh-squeezed lime juice and fish sauce. Usually, it’s tossed and marinated like ceviche, but we’re thinking about doing a contemporary plating on it, similar to beef carpaccio. We’d offer a vegan iteration with king trumpet or portobello.

"Oh, my god, another item I can’t wait to offer is giant fire-grilled river prawns, which they call river lobsters! Butterflied and served with a garlicky Cambodian citrus-herb sauce and kroeung curry butter! Umami, bright, rich, herbaceous. Or how about banana-leaf-wrapped whole fish that’s grilled with tons of fresh veg and herbs? Very family-style and community-oriented.”

Another favorite dish from Karuna’s childhood that’ll be at Sophon is samlar kako, a hearty curry stew with kabocha squash, winter greens, and catfish, with toasted rice powder added to thicken it up, cooked in a clay pot. He’d also like to do a Khmer-style brunch program, including a garlicky pork broth with noodles called kuyteav, which is a common breakfast in Cambodia.

"Oh, we also want to do Cambodian hot pot called yao hon as a family option on Sundays. The broth is made with a house recipe, and we’d serve it with all the accoutrements, fresh veggies, and a choice of meat or vegetarian protein. So then everyone can experience what my brothers and I did when it was our birthday or whatever, and my mom would bring out the hot pot!”

As he talks, it’s clear that Karuna kinda lives for these community dinners—as evidenced by the fundraiser barbecue held in the driveway of Oliver’s Twist last month. This guy was just in bloom, a natural party host. Again, he was on the floor greeting everyone by name, and they all got a som pas, the traditional Cambodian greeting of prayer hands and a slight bow. Even behind the grill, Karuna was still kibitzing with guests and cracking wise.

God, by the way, the memory of these grilled egg noodles they had at the Cambodian barbecue, dressed with parmesan, garlic, sesame, and lemongrass, is still razor-sharp for me, weeks later. These things disappeared the very second they were tonged into the little cardboard boats; people could not get enough. Reminded me of the famous garlic noodles at San Francisco’s Thanh Long, but lord, so many noodillions of times better. The kroeung curry smashburgers, spiced with ginger and lemongrass and topped with American cheese, made a deep impression on me too. Karuna’s cousin Darwin was both the noodlemaster and the burgermeister at that station, so all credit goes to him.

I snapped a photo of the grill for Instagram—and four different people DMed me before the day was done, asking where they can get hooked up.

“Well, we’re having another Cambodian barbecue on the second of April,” Karuna tells me, “so tell them to come through.”

In addition to opening the floodgates on culinary inspiration, the recent Cambodia trip really opened Karuna’s eyes, he says, about his family’s origins. “I was a little brat the last time I had the chance to visit Cambodia. I was a teenager, was hanging out with gangs in Long Beach, getting in trouble. So I didn’t appreciate the opportunity then, seeing where we come from. But going back in January, I don’t think there was a moment on the whole trip when I wasn’t, like, welling up with tears. Just seeing how courageous and resilient everyone is. How they lived through it all.”

He regales me on all the culinary research he did while he had boots on the ground in Cambodia. “Dude, there were dishes that I’d never ever been introduced to. My aunt, my dad’s older sister, was there as well, and also my great aunt, who lives there, and I was picking their brains. Asking, ‘What is this, why do we do this, why is it only available in this region?’ I learned a TON from these women. So, basically, I want to be able to tell the story of the dishes and change the narrative on them, where the story doesn’t have to be, ‘We eat this because we’re so poverty-stricken,’ anymore. I can serve a version of it where we aren’t, and adapt the dish to be more full, more luxurious.”

***

When asked how the Khmer Rouge-led genocide ties into the concept behind Sophon, Karuna says, “Well, it’s kinda the whole point, to tell this story. I want this space to be filled with love, light, and life to honor our mom, all the matriarchs in our culture, and all of our Khmer ancestors lost during the Khmer Rouge era and its aftermath. I want Sophon to serve not only us but the whole community, so we can tell the story through food and culture. I think it’s actually something that frequently gets left out of the conversation when talking about Khmer cuisine in the US.”

The Khmer Rouge era can be difficult for non Khmer-icans to comment upon because we’re taught so very little about it, and that’s on purpose. Until a few weeks ago, the bulk of what I personally knew about the Khmer Rouge was learned from watching The Killing Fields decades ago. We know all about the simultaneous Vietnam War, since Americans were dispatched there to fight and returned home to tell the tale. But there are no Alice in Chains songs or long-running TV dramas about the atrocities performed in Cambodia.

However! One thing that I did know, and that it’s impossible not to think about when considering any facet of Khmer culture, is Anthony Bourdain’s quote about how you’ll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death once you visit Cambodia. Bourdain was referring, of course, to the US-led bombings between 1969 and 1973 meant to prevent Cambodia from being used as a sanctuary by the People’s Army of Vietnam, with which the US had been at war for a decade. These airstrikes killed as many as 150,000 Cambodian people in total—with the US government assiduously denying it all the while. We’re not supposed to know about what happened in Cambodia, because then we’d know our nation is complicit. It’s by design.

A grim turn from a fun article about yummy dinner, yeah, but since we were already talking about genocide… it seems delinquent not to point this out. The Nixon Admin bombed Cambodia for four years, then refused to help them during the subsequent holocaust and struggle to rebuild—as did the UN and the rest of the world, and then everyone all silently watched for decades as the shadow of the war in Cambodia grew longer. In the way they teach little German children all about Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen, Americans should know this stuff. It’s American history as much as it is Cambodian.

On top of that, the subject of food as it relates to Cambodia historically is a complicated and intensely emotional one. Americans may be aware of the labor camps and mass slaughter led by the Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979, but most of us don’t know that severe famine killed at least half a million Khmer people, and probably twice or thrice that amount.

“Yeah, as we learned early on,” Karuna says, “food is a gift. Considering what our parents and so many other Khmer elders went through during the dictatorship, too many succumbed to starvation for us to take the gift of food for granted.” He says this factors heavily into the Sophon project as well, into the story he wants to tell.

***

The Sophon project has a home at last, but Karuna and his crew still need to fund-raise to make it a turnkey situation. “At this point, it’s just cash flow that’s keeping us from moving in,” he says. With the Kickstarter scrapped, the new donation platform has some cute prizes: a gift of fifty bucks gets you a handwritten thank-you note with a Khmer recipe, $100 gets you a Khmer barbecue sampler OR a 175-dollar gift card, and $200 gets you two tix to the Sophon housewarming bash. Or you can just no-strings donate via PayPal.

Seattle needs Sophon. We have, at last count, only two other joints that offer Khmer food—that’s Angkor Wok and Phnom Penh Noodle House, unless you also count Apsara Palace and Theary Foods, in White Center and Tukwila respectively—and while all are important, they all serve pretty traditional Khmer stuff. What Sophon will be bringing to the table is much broader, not only in the classic-meets-contemporary Khmer menu but also the physical building itself, as a true community space. Seattle doesn’t have ANYTHING like this. It will fill a void for the Khmer community—as well as a void in Seattle’s bellies, both Khmer and non-Khmer.

Karuna’s a dreamer, and he’s dreaming big on this one, but it’s hard to doubt him for a second. These dreams are innovative, clever, exciting, and attainable, and this guy’s as resilient as they come. The saga of Karuna, his mom, his brothers and his cousins, and their tiny-ass kitchen overcoming the odds and still persevering on their dreams is the stuff of those over-auteuristic food shows on Netflix with the Vivaldi soundtracks. I found myself getting emotionally invested just from reading about this shit, long before I’d ever met the guy.

“Look, here’s the thing,” Karuna says. “After traveling to Cambodia and just seeing how gracious and kind everyone is, after all the devastation they lived through, even if the fundraising fails, it’s like… I’m still very fortunate to be here. You know? It’s a privilege to even have the opportunity to try to make this community space exist.”

He wraps it all up with a som pas and his slogan: “We’re resilient! Either way, I know we’ll figure it out."

In addition to the online fundraising campaign for Sophon, that second Cambodian barbecue fundraiser will be on April 2 in the driveway at Oliver’s Twist at 6822 Greenwood Avenue North from noon to 5 pm. It’ll be open to the public and running on donations. Follow @oliverstwistseattle on Instagram for details, and pray to the skies that Darwin’s grilly lemongrass noods will be making an appearance.