After a haze of wildfire smoke choked Seattle residents this month, environmentalists told the Mayor to stop dragging his feet on legislation that would limit pollution from buildings, which accounts for one-third of the City’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

The regulations feel “too little, too late” for some climate justice advocates, but if the City does not act before budget negotiations begin, they fear the Mayor will have set up the policy for failure. After all, the incoming 2024 City Council may be more sympathetic to big business and property owners, the high-polluting interests that environmentalists blame for the frustrating concessions and delays that already squander bold, local action on climate change.

Climate Change Waits for No One, Not Even a Mayor

This June, Mayor Bruce Harrell promised to implement wimpy building emission performance standards (BEPS) requested by the Durkan Administration that would add to Washington State’s even wimpier Clean Buildings Act.

The BEPS set various emission regulations and reporting requirements for buildings larger than 20,000 square feet. That size includes about 1,650 nonresidential buildings such as hotels, office buildings, retail spaces, and almost 1,900 apartment buildings, mostly those with 20 or more units. According to the Mayor’s press release, the BEPS will decrease building emissions by 27% in 2050 compared to a 2008 benchmark, which would roughly equate to booting more than 70,000 cars from the road for a year.

The Mayor disappointed the Sierra Club and 350 Seattle organizers when he failed to transmit the bill to the council earlier this week, which would have allowed the council to pass it in September.

In an email to The Stranger this week, Mayoral spokesperson Jamie Housen said Harrell “remains strongly committed” to BEPS.

Housen wrote that the Mayor is taking it slow to “ensure this critical, groundbreaking, and complex legislation receives appropriate consideration”—even after the City’s two-year stakeholdering process. Harrell plans to submit the policy to council after the passage of the City budget in November, a timeline that will “not delay any of the critical implementation milestones in the proposed bill, nor impact its urgency once adopted,” according to Housen.

Seattle Loves Rich Property Owners

Not only does it seem silly to waste any time on urgently needed climate action, but waiting until after the budgeting process would likely put the policy in the hands of the next city council. The council will gain at least four brand new members, who will likely need a few months of preparation to work on a matter as complex as the BEPS. Plus, depending on the results of the November election, the current council may be the most likely to strengthen the policy—or at least not further water it down.

Environmental groups such as 350 Seattle and the Sierra Club already criticize the policy for its slowness and its loopholes, which they argue come from the outsized influence of big business and real estate in City Hall.

The policy got even weaker since Durkan first ordered the Office of Sustainability and the Environment (OSE) to develop it in November 2021.

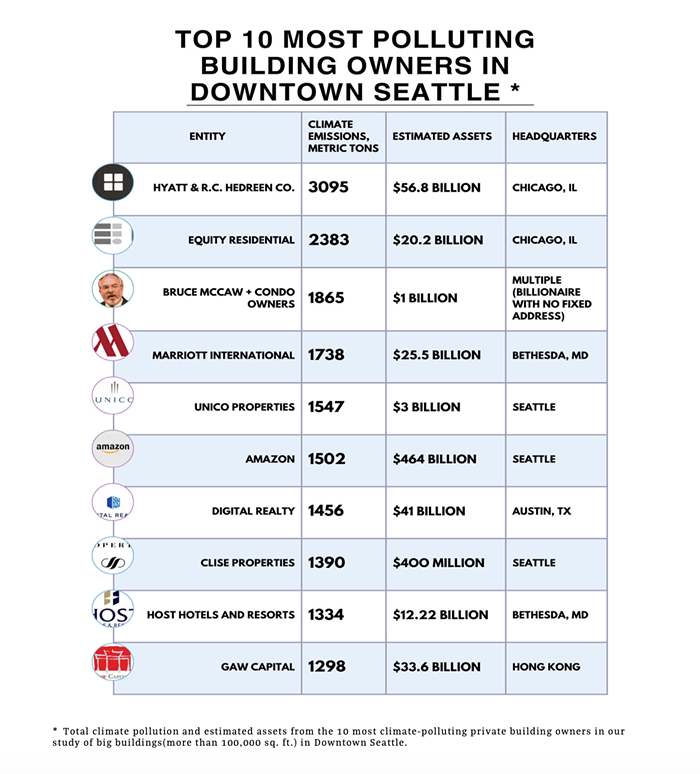

Many of those changes happened after the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, the Downtown Seattle Association, and the Commercial Real Estate Development Association (NAIPO) sent a joint letter asking the Mayor not to implement BEPS during downtown’s “fragile” recovery from the pandemic. On top of that, half of Seattle’s top-ten highest polluting building owners donated to Harrell’s campaign, including R.C. Hedreen Co, which earned the top spot. And the real estate industry made up for more than half of Harrell's contributions, according to 350 Seattle (To see the researchers' methodology, click here.)

According to her executive order, to align with City’s 2019 Green New Deal commitment Durkan wanted the new standards to reduce building emissions by at least 39% in 2030 compared to the 2008 baseline. Harrell’s plan pushed back that decarbonization timeline by two decades.

The City also pushed back the first compliance deadlines by five years compared to a January 2023 draft. According to a recent report from 350 Seattle, the five-year delay will cost the City an additional 1.5 million metric tons of climate pollution, or a 46.5% increase from the old plan.

Expectations in Harrell’s plan for the biggest buildings to pursue a more gradual path to net-neutral emissions will result in almost 500,000 more metric tons of pollution, according to 350 Seattle’s report.

350 Seattle argues that companies who own big buildings can afford to comply quickly. According to their research, more than 70% of the entities that own Seattle’s biggest, most polluting buildings boast at least $5 billion in assets. More than half of the owners the group studied have more than $10 billion in assets, and four owners hold at least $1 trillion in assets. Only 3% of buildings affected by BEPS are owned by individuals, and the report notes that most of those big-building owners are probably not struggling financially.

Environmentalists worry that wealthy building owners will take advantage of “pay to pollute” schemes that allow owners to skirt standards for a relatively modest fee that got even smaller during “stakeholdering” negotiations. In the latest draft, property owners can pay $3.33 per square foot every five years (or $2.50 per square foot for multifamily buildings) to avoid decarbonization. For comparison, a similar policy in Washington D.C. charges $10 per square foot every five years. The City won’t collect the first of these fees until 2032, “codifying more than almost a decade of inaction without consequences,” according to the 350 Seattle report.

To make the policy more effective at tackling emissions, advocates propose amendments to speed up timelines and cut the pay-to-pollute schemes entirely. Since Seattle could be the first place in the Pacific Northwest to implement BEPS, setting a high standard is particularly important.

But even without these changes, the environmentalists want the policy passed as soon as possible. As the Mayor’s spokesperson told The Stranger in an email, Harrell ran on acting as climate justice champion. Climate justice advocates are waiting for him to prove it.